“The bank was located on El-Batrak Street (present day David Street) in the Old City, near the vegetable stalls and the grocery stores, which also sold fish. The bank itself was situated between two vegetable stalls, whose crates took up a large part of the street. You would enter via a narrow passageway, at the end which there were two spacious rooms, where Aharon Valero ran his banking business.” That’s how Gad Frumkin described Jacob Valero & Company, the first private bank in pre-State Israel, in his book Derech Shofet B’Yerushalayim – The Path of a Judge.

The bank’s founder, Jacob (Ya’akov) Valero, a scion of a family expelled from Spain, was born in Istanbul in 1812. After receiving a traditional Jewish education, he decided in 1835 to emigrate to Israel. He arrived in Jerusalem penniless, equipped with documents certifying that he was a shochet (a ritual slaughterer of kosher meat) and a bodek (an inspector who examined the health of the animals’ inner organs before they were slaughtered), which was the only way to make a living in the Jewish community in the city. But much to his disappointment, the Jews in Jerusalem informed the new immigrant that there was an abundance of shochets and bodeks, and for that reason there was no demand for his profession.

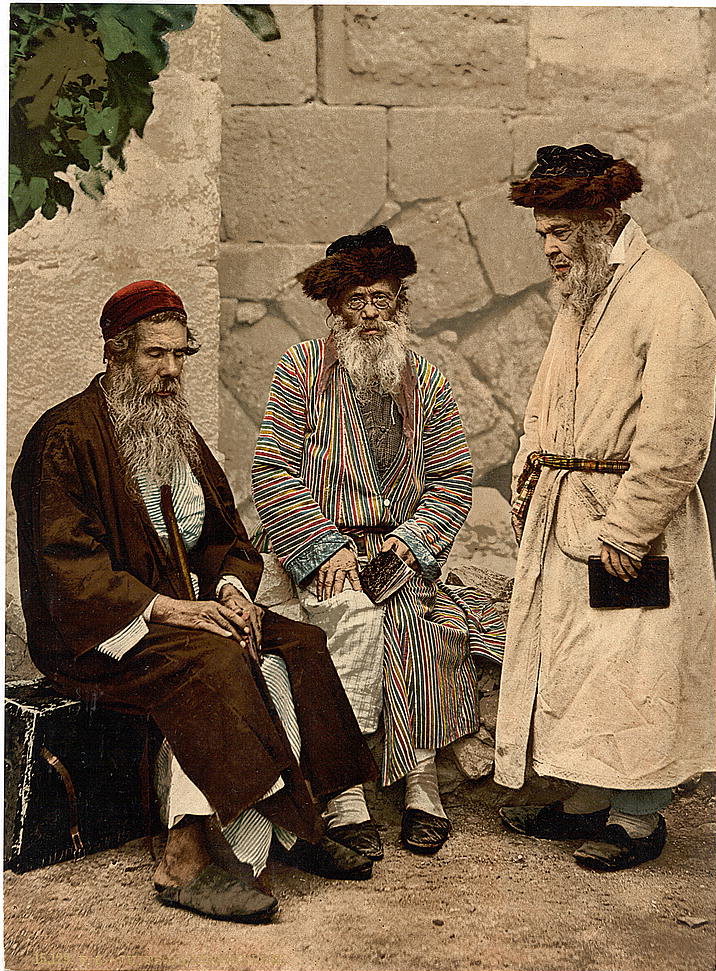

At the time, Jerusalem was a major hub that drew pilgrims, traders, researchers and tourists from France, England and Russia. All of them tried to persuade the local merchants in the Old City to accept payment in British Pounds, Russian Rubles or French Francs. Seeing this, Jacob identified an opportunity to make a career change and became a moneychanger. He took a chair and a small table and set up shop in a corner of the market.

Many people availed themselves of the services that Jacob provided. Apart from changing money, a growing number of customers who had confidence in his integrity would leave large sums of money with him when they left the city – whether to bathe in the Sea of Galilee or visit the surrounding holy sites that were popular with the pilgrims.

In 1848, Jacob Valero and his two partners, Haim Amzalak and Giacomo Pascal, open the first private bank in pre-State Israel – Jacob Valero & Company. The bank’s initial capital amounted to three million francs. The first branch was opened in a two-room apartment close to Jaffa Gate in the Old City.

Valero’s natural business sense was right once again. His clients included Jerusalem’s most affluent residents, senior government officials, and also European organizations that sought to expand their influence in the region. To meet the high demand, two more branches were opened: one in Jaffa, managed by Jacob’s eldest son, Moshe Yosef, and another branch in Damascus, which at the time was considered the largest and most important city in the region.

Jacob’s youngest son, Haim Aharon, started working in the bank at the age of fifteen. He was an intelligent young man who quickly learned the ins and outs of the business. In 1875, Haim Aharon was appointed manager of the bank’s branch in Jerusalem.

At first, most of the services provided by the bank were to the local population: deposits, loans, and money transfers to and from organizations. Some of those transfers included money that was raised from Jews overseas – known as halukkah funds – to support Torah and Talmud scholars in Jerusalem. Later on, the bank also began providing financial services to Russian pilgrims, who came to Jerusalem in very large numbers after the Russian Orthodox Church bought up land in the city, including in what is now known as the Russian Compound.

Jacob Valero & Company also had other, and no less important, clients, such as Franz Joseph himself, the Emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He utilized the bank’s services to manage the numerous interests of the Empire in Jerusalem. Baron Edmond de Rothschild, another prominent client, used the bank to transfer money to the many projects funded by his family in Jerusalem and throughout the country.

Jacob Valero died in 1874 and was buried on the Mount of Olives. A countless number of Jews and representatives from foreign countries attended his funeral. Out of respect for the deceased, the Austrian Consulate lowered its flag to half-mast. Six years after his death, Jacob’s eldest son, Moshe Yosef, also passed away, after which Haim Aharon was appointed general manager of the bank.

Haim Aharon, who had already proven his banking skills, also enjoyed a high social and political standing. The Austrian emperor conferred the Red Cross knighthood medal on him, in addition to making him a subject of the Empire. The Russians awarded him with the medal of the Order of Saint Anna, and the Ottoman government appointed him to be a member of the city council as well as a magistrate in the local court.

The members of Sephardic community also treated him with great respect, and for 25 years Haim Aharon headed the Sephardic Community Committee in Jerusalem. He was also one of the representatives of the Moses Montefiore Memorial Trust, which helped build homes for Jews in the new neighborhoods of Jerusalem.

Haim Aharon Valero and his wife Esther (née Levi) had five children. They lived in a big and elegant house near Herod’s Gate, which was designed by Conrad Schick, a German architect, archaeologist and missionary who also lived in Jerusalem. To commemorate his daughter Malka who died as an adolescent, Haim Aharon bought a large lot on which he built a hospital in the city, which later became Shaare Zedek Medical Center. Haim Aharon was known for his philanthropy and the assistance he extended to the needy. After coming up with the idea of building the Old Age Home for Sephardic Jews in Jerusalem, he bought the land and personally oversaw the construction. Upon its completion, he also served as president of the home for many years.

The purchase and sale of land and real estate comprised a large part of Haim Aharon Valero’s business dealings. Most of the lots that he bought were on or in the vicinity of Jaffa Road. The Mahane Yehuda market would later be built on one of those lots. Additionally, the northern section of what would become King George Street was paved on another lot that he owned.

Haim Aharon Valero was also known for his good relations with the Arab population in Jerusalem. They extended beyond business connections with wealthy residents and were genuine ties of friendship. Valero also donated money to institutions in the Arab community, including the Red Crescent Society, because he believed that enabling all the local population groups to enjoy prosperity was the only way to ensure the prosperity of the city itself.

It’s not clear whether Haim Aharon Valero expected his sons to join the family business. We do know that he was very annoyed with them because of their extravagant lifestyle and indifference to religious traditions. Two of his sons decided against arranged marriages which were meant to sustain the family’s standing, and chose instead to marry out of love. And contrary to what their father had hoped, both of them ended up marrying Ashkenazi women who were not from well-established and respected Sephardic families. Haim Aharon also boycotted the wedding of one of his sons that was held in far-away Minsk, even though he paid for the rest of the family to travel there. On the other hand, he was one of the first supporters of a joint Sephardic-Ashkenazi committee, believing that it would better represent the community as a whole. Despite everyone’s good intentions, the committee lasted only a few weeks and was disbanded due to internal disputes.

Another son was involved in a love triangle that stirred up a storm in Jerusalem. Yosef-Moshe Valero was courting Leah Abushedid, who came from the right ethnic background and a rich family. The parents on both sides had already started planning the wedding, but then a new suitor suddenly appeared on the scene. He was Ashkenazi and poor, and his name was Itamar Ben-Avi. To compensate for his lack of wealth, he began publishing his love letters to Leah in HaTzvi, a Hebrew newspaper published in Ottoman Palestine.

Everyone in the city closely followed the weekly publication of the letters for a period of three years. Eventually, when he realized that he had no other choice, Itamar Ben-Avi threatened to commit suicide if Leah would not agree to marry him, a threat that he also made public in his newspaper column. To prevent the loss of life, the family gave in and consented to the marriage.

Another affair associated with Yosef-Moshe occurred several years later when he was serving as a district judge in the British Mandate courts. It was during the high-profile trial of the men accused of murdering Haim Arlosoroff, and Yosef-Moshe was one of the justices on the panel. He wrote the dissenting opinion that supported dropping the charges against the defendant Avraham Stavsky, who was a member of the Etzel underground movement. It appears that Yosef-Moshe was not afraid to adopt a position unpopular with the heads of the Jewish community and the British authorities that wanted to convict and execute Stavsky. In the end, he was acquitted on appeal by the Supreme Court.

Haim Aharon Valero died in 1923. Like his father Jacob, he too was buried on the Mount of Olives. Jacob Valero & Company, the first private bank in pre-State Israel, closed its doors in 1915, at the height of World War I when Jerusalem was poverty- and hunger-stricken. In the last years of his life, Haim Aharon lived on the ground floor of one the buildings owned by the family on 51 Jaffa Road. On the floor above, there was a synagogue named Shivat Zion, which is still in use today.

The descendants of Haim Aharon Valero chose to follow in the footsteps of his son the judge. In 1939, Haim Aharon’s grandson, also named Haim Aharon Valero, opened one of the first law firms in the country. The firm, which specializes in real estate law, is currently managed by that grandson’s grandson, Attorney Moshe Valero, in partnership with his son, Oren Valero. In 2012, the Municipality of Jerusalem dedicated Valero Square, located on the intersection of Jaffa Road and Beit Yaakov Street across from the Mahane Yehuda market.