Herbert Pike Pease had no idea what had hit him and where it came from. He was at the height of his political career, initially as Darlington’s Liberal Unionist Party representative in the House of Commons. In those days, at the beginning of the 20th century, the Parliament was an island of stability in the stormy seas of British politics. After the title of 1st Baron Daryngton was created for him, he also served in the House of Lords. Following his retirement, which came after serving a total of 25 years in Parliament, his peerage was inherited by his son.

But in the 1910 elections to the House of Commons, halfway through Pease’s career, an unexpected rival by the name of Trebitsch Lincoln suddenly emerged on the scene. He was a Jewish immigrant from Hungary who had converted to Christianity and had been working as a missionary in Canada. As a candidate of the Liberal Party, Trebitsch Lincoln was backed by a family of local chocolate manufacturers. At the time, the Liberals were facing a sharp decline in public support and Trebitsch Lincoln’s candidacy was dismissed as a bad joke. In retrospect, it was truly a grave and bitter mistake to underestimate him. In fact, the nondescript incumbent that he ran against did not stand a chance against one of the greatest tricksters in history.

Import tariffs were one of the main issues on the public agenda at the time the elections were held. Trebitsch arrived in his constituency and introduced himself as Timothy Trebitsch Lincoln. The addition of Lincoln to his name stemmed from his admiration for the legendary American president, whom he viewed as a role model. He told the local voters that whereas they had been born British by chance and by default, he on the other hand had chosen to be an Englishman out of a genuine love for the British way of life.

The brazen candidate set out on a tour of mainland Europe, from which he sent promotional stories back to newspapers in Britain. For example, The Northern Echo published that in some German cities people were forced to eat their pets due to the economic situation caused by protectionism. Trebitsch also declared with great confidence that he would beat Pike Pease by exactly thirty votes.

On election day, it appears that quite a few voters looked fearfully at their pet dogs and cats before casting their votes and giving Trebitsch Lincoln a 29-vote victory. The newly elected Parliament was dissolved after only one year and Trebitsch did not run in the next election. By that time he was already in Budapest, where he was raising money for speculative oil investments in Romania. This was one more stop on the journey of a tireless charlatan.

It is difficult to say whether something in the background of Ignatius Timothy Trebitsch Lincoln – or of Chao Kung, Leo Tandler, Moses Pinkeles, or any other of the multiple false identities he assumed over the years as needed – could have predicted the highly unusual course that his life would take and that he would change his religion at least three times and betray four or five countries.

He was born in 1879 to a very wealthy Orthodox Jewish family in Paks, a town located 120 kilometers south of Budapest. His father was a grain trader and his mother was a distant relative of the one of the branches of the Rothschild family. As a child, he studied in a yeshiva, but also received an excellent secular education and was conversant in French and German by the age of ten. Around that time, his family moved to Budapest to capitalize on the fruits of the golden age that characterized the city. With public thermal baths, thriving theaters and electric street cars, between 1880 and 1910 Budapest was considered one of the best cities in the world. And no less important – it offered Jews amazing opportunities in fields which in previous generations and in other places they did not have access to.

His older brother developed a keen political awareness and like many Jews around him changed his name to a Hungarian name – Lajos Tarcai. He became the editor of a newspaper and a socialist leader who emigrated to the United States in 1910. Another brother in the family – Vilmos – led a more conventional life and worked as a banker. Years later, like many of Hungary’s Jews, he was murdered in the Auschwitz death camp.

The young Ignácz, our protagonist, ironically chose a career as an actor and attended the Royal Hungarian Academy of Dramatic Art. In the meantime, the family loses a lot of their money in speculative stocks. To compensate for his lost income, Ignácz begins stealing watches. After an unrequited love for a young actress puts an end to his professional acting career, he sets out on a journey around the world, which essentially will never end. At the beginning, he would send stories from his travels to local newspapers in Budapest, mostly about South America – a continent which he apparently never stepped foot in.

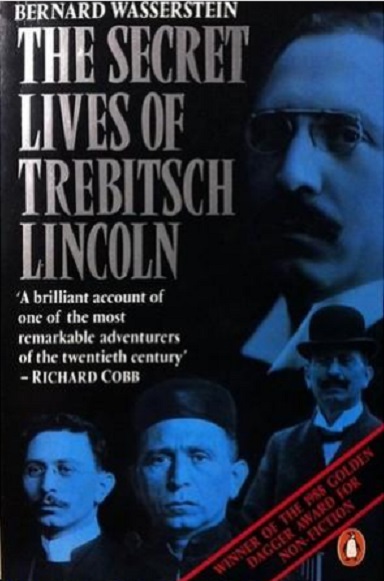

Before we continue with an abridged account of his life story, it should be noted that the main source of information about Trebitsch Lincoln comes from Bernard Wasserstein, one of the most important historians of the Jewish people in our times. His highly pessimistic book – Vanishing Diaspora – deals with the disappearance of European Jewry after World War II. Among the long list of books that he wrote about European Jewry and the British Mandate in Palestine, he also devoted a considerable amount of time to researching the life of Trebitsch Lincoln. He published that research in a book entitled The Secret Lives of Trebitsch Lincoln. It is no coincidence that he chose the word “lives” instead of “life.”

Trebitsch arrives in London in 1899, where he apparently has little, if any, money. After being taken in by a Mission to the Jews, he is baptized by a local reverend named Lypshytz, himself a converted Jew who ran a mission that aimed to baptize destitute Jews. Trebitsch begins his life as a Christian on the wrong foot after stealing a watch that belonged to Mrs. Lypshytz.

From London he goes to Germany, where he is ordained as a priest, and from there travels to Canada, where he works as a missionary for Irish Presbyterians. It does not take long for Trebitsch to be at odds with them, after which he aligns himself with their rivals, the Anglican Church. At the time, Ireland was fighting for its independence from the British. The Archbishop of Montreal was so impressed by the young preacher that he even predicted that Trebitsch would succeed him one day. Even though Trebitsch proved to be a highly inspirational preacher, he still failed, thank goodness, to fulfill his primary task – converting Jews to Christianity.

In 1903, he returns to England and for reasons only known to him, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the head of the Anglican Church, appoints him a curate at a parish in the county of Kent. During his many travels throughout Britain, on one of his train trips he meets Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree, a major chocolate manufacturer who will later finance his political career. Rowntree makes Trebitsch his private secretary and sends him to mainland Europe to do research on poverty. Trebitsch then writes a book for Rowntree on public policy, which subsequently became a key element of the Liberal Party’s platform. This was a recurring pattern in Trebitsch’s life: he had the ability to represent and promote any ideology or religious worldview with the passion of a missionary, draw large crowds of people and cause them to do foolish things, such as handing over their money to him.

After the aforementioned elections and leaving the House of Commons, Trebitsch relocates most of his business dealings to the Balkans, where he manages to convince investors to put their money on Romanian oil wells, even though they had dried up long before that. Another idea he had was to create a monopoly over the pipeline network in order to control oil prices. He lived next to the Romanian royal palace and his business ventures had the support of the Romanian government. His idea actually made a lot of sense. The decision made by Winston Churchill, who at the time was serving as First Lord of the Admiralty, to have the royal fleet switch from coal to oil turned oil into a natural resource that would dictate the history of the 20th century. It is unfortunate that the wells in Romania could produce no oil.

After the outbreak of the First World War, Trebitsch started working as a double agent. He worked as a censor for the British and at the same time sold secrets to the Germans. There is a considerable lack of consensus among historians about what he actually was engaged in, with some of them linking him to a Greek arms dealer named Basil Zaharoff. After his cover is blown, Trebitsch flees to the United States, which was still a neutral country at the time. He publishes a book there in which he claims to expose “British war secrets.” Following pressure by Scotland Yard, the Americans arrest him. But, needless to say, he immediately offers his services to the U.S. intelligence agencies, promising to sell them secrets – this time German ones.

The Americans believe him, set him up in an office in New York and even assign him a bodyguard, until they finally succumb to British pressure and take him into custody. However, not long after his arrest, Trebitsch becomes a folk hero following a successful attempt to escape from the Brooklyn jail where he was being held – which for many people brought to mind the feats of another Hungarian Jew in those days – Harry Houdini. The Americans eventually manage to apprehend Trebitsch and extradite him to Britain, where he is sentenced to three years in prison. While serving his sentence, he develops an intense hatred for everything British, which can explain the choices he makes in the remaining years of his life.

After his release from prison, Trebitsch leaves Britain and goes to Germany, where he contacts an army officer named Max Bauer who was known for his radical rightist views. Both of them then collaborate with Wolfgang Kapp and help carry out the famous putsch to overthrow the Weimar Republic, following which Kapp forms a government. And Trebitsch, who until recently had been incarcerated in Britain, is now appointed Director of Foreign Press Affairs in the new regime. But Kapp’s government lasts only a couple of days. Trebitsch is apprehended in Berlin and taken into custody, only to break out of jail and flee to Hungary, while using a variety of false identities and disguises. Once in Hungary, he makes contact with antisemitic right-wing groups and together they devise the White International plot, which sought to encourage popular insurrections in Europe and bring about the annulment of the Treaty of Versailles.

It does not take long for the people on the far right with whom Trebitsch has aligned himself to realize that he is causing more trouble than good and that his endless escapades could endanger them. So, they decide to assassinate him. Various bits and pieces of information from that period indicate that Trebitsch may have had ties with Adolf Hitler or Miklós Horthy, Hungary’s antisemitic head of state. Horthy ruled from 1920 to 1944 and the Holocaust of Hungarian Jewry occurred under his watch. According to one of the allegations made against him, Trebitsch also extended assistance to the Nazi movement, using the name Moses Pinkeles as an alias.

Trebitsch apparently understood that because of his Jewish roots his ties with the right-wing extremists in Europe could end with a knife in his back, and not only metaphorically. So, he decides to make a run for it again, this time taking with him a suitcase full of documents that could incriminate those right-wing groups. He tries to sell the information in his possession to the British and the French, but without any success.

He is eventually arrested in Vienna, after which he is deported. He then makes his way to Japan in 1922 and from there to China, where he joins the inner circle of Wu Pei Fu, a warlord who was deeply involved in the never-ending civil wars in that country. In the years that follow, Trebitsch assists the Japanese in their efforts to seize control of Manchuria, and by doing so contributes to the collapse of the British Empire in Asia.

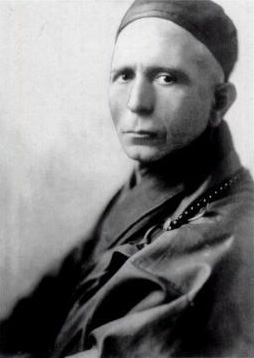

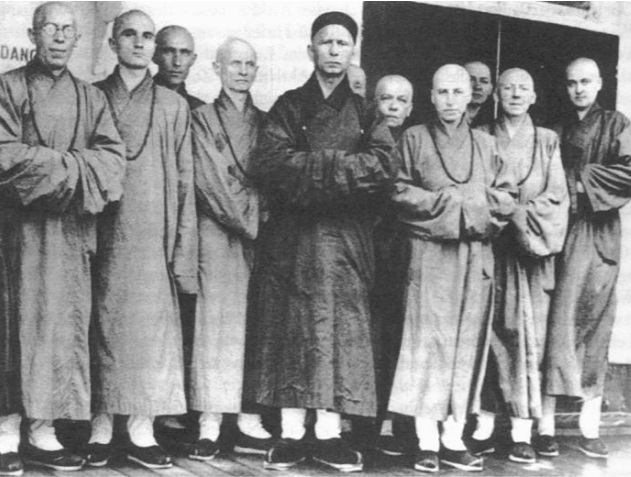

In 1931, Trebitsch decides that the time has come to revitalize his beliefs and the religious aspects of his life. So, he is ordained a Buddhist monk and changes his name to Chao Kung. A number of researchers believe that his connection with Buddhism was actually authentic and reflected a genuine commitment on his part. After opening a monastery, Trebitsch also founds a sect that even the Soviet ambassador to China takes an interest in. Furthermore, Trebitsch goes back to Europe to promote Buddhist missionary causes.

After the start of World War II, Trebitsch establishes contact with a Nazi official and offers his services, but that offer is rejected by Reinhard Heydrich (the chief of the Reich Security Main Office) because of his Jewish origin. And believe it or not, following the death of the Panchen Lama and the Dalai Lama of that period, Trebitsch, who was already 60 years old, tries to persuade Heinrich Himmler that it would be a good idea to appoint him their successor and proclaim him the 13th Dalai Lama. Contrary to the Nazis, the British and the Tibetans were not keen on the idea and Trebitsch never makes it to Tibet.

Against the backdrop of the raging war, he writes a letter to Hitler demanding that the murder of the Jews be stopped. In response, the Nazi Command orders their Japanese allies to execute Trebitsch after they seize Shanghai. As outlandish as it may sound, at the time he was regarded an important intellectual figure in Shanghai who oversaw Buddhist study sessions and rites.

In view of all the religious conversions he underwent and the self-serving ties he forged with antisemitic right-wing movements in Europe, it appears that Judaism was only a distant memory in Trebitsch’s mind. Strangely enough, the last piece of documented information that we have about him comes from an interview that he gave to a Yiddish weekly published in Shanghai. During that interview, he spoke about his solution to the Jewish problem, which entailed settling Jews near that major Chinese city. The interview was published in June 1943, and in October of that year Ignatius Timothy Trebitsch Lincoln passed away.