In the midst of the uproar surrounding the ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States that overturned a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion, many have tried to assess what actual impact the Court’s decision will have. The optimistic interpretation offered by abortion opponents is that the overturning of Roe v. Wade will lead a reduction of about 20 percent in the number of abortions that are performed. But the invention that lowered the abortion rate most dramatically was the birth control pill. So, this time we will talk about three Jewish scientists who were among its inventors.

In his book Genius and Anxiety, the British-Jewish historian, Norman Lebrecht, a former yeshiva student, wrote that among the inventors of the pill, Gregory Pincus was the one whose work was affected by Jewish tradition. Not religious tradition, but the Talmudic methodology. Whereas the various types of birth control that people had tried prior to the advent of the pill focused on the conception process – namely, preventing sperm from reaching and fertilizing an egg – the pill embodied a different idea – one of “reverse engineering.”

According to Lebrecht, “Pincus suggests a hypothesis: in what kind of situation can a woman have unprotected sex and not get pregnant? The answer is clear: if she is already pregnant. Consequently, science has to imitate a state of pregnancy, and then a woman will be free of the risk of conceiving.”

Gregory Goodwin Pincus was born in New Jersey in 1903 into a family of immigrants from Russia. He initially studied Agriculture at college, following in the footsteps of his father who was the editor of a farm journal. After that, he went to Harvard where he studied Physiology and Genetics. One of his first scientific achievements was in vitro fertilization of rabbit eggs without using the sperm of a rabbit. This groundbreaking in vitro fertilization of a mammal did, however, put Pincus in the hot seat. At a conference in Toronto, he announced that he had no intention of applying these techniques to human beings. But someone deleted the word “no” from the press release and all hell broke loose.

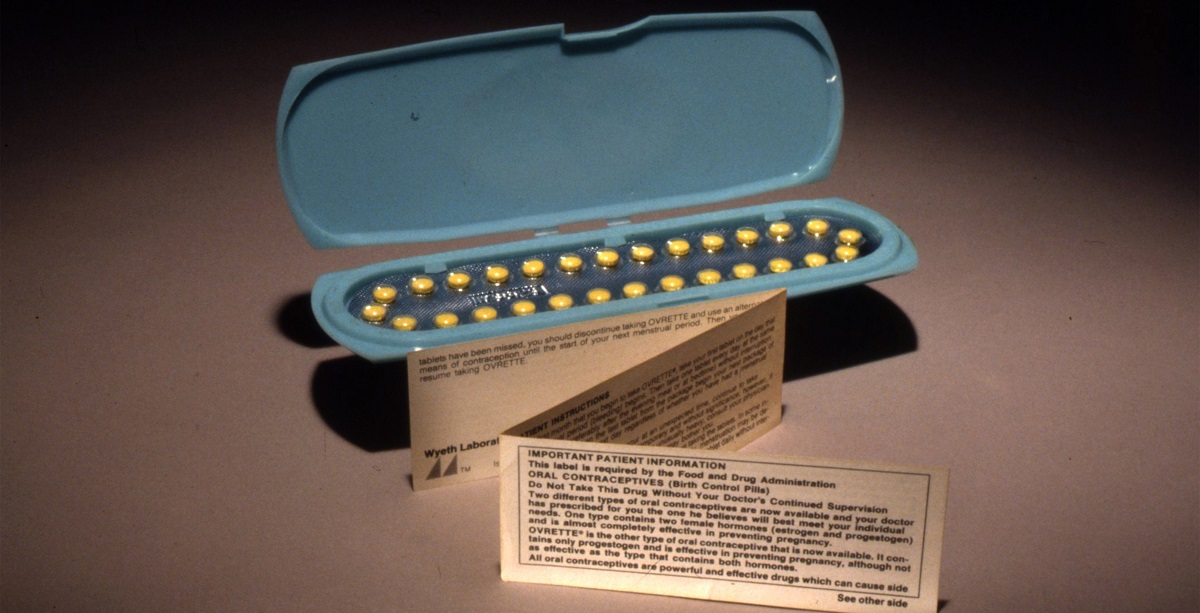

A furious New York Times called him “Dr. Frankenstein” and Harvard University revoked his tenure. But like what frequently happens in science, important discoveries are made in life outside the mainstream. After Clark University in Massachusetts gave Pincus a research grant, he founded the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology and recruited a local rabbi to serve on the board. He then teamed up with a feminist by the name of Margaret Sanger, a leading birth control advocate, and with a Catholic gynecologist by name of John Rock, who were determined to find a contraception method that was more effective than the ones in use at the time. In 1951, they began conducting experiments with norethisterone – a type of synthetic progesterone. Pincus continued to contend with ethical issues in that research as well. Many of the clinical trials were carried out in Haiti and Puerto Rico, and some of them on women who were hospitalized in mental institutions. But the trials substantiated the theory – hormones could in fact be used to ‘convince’ the body that it is already pregnant.

However, the theory also has to coexist with the praxis. It was ironic that the physiological idea was formulated by someone who had started out studying agriculture, whereas the synthetic form of the progesterone that came from plant sources was created by scientists whose training was in physiology.

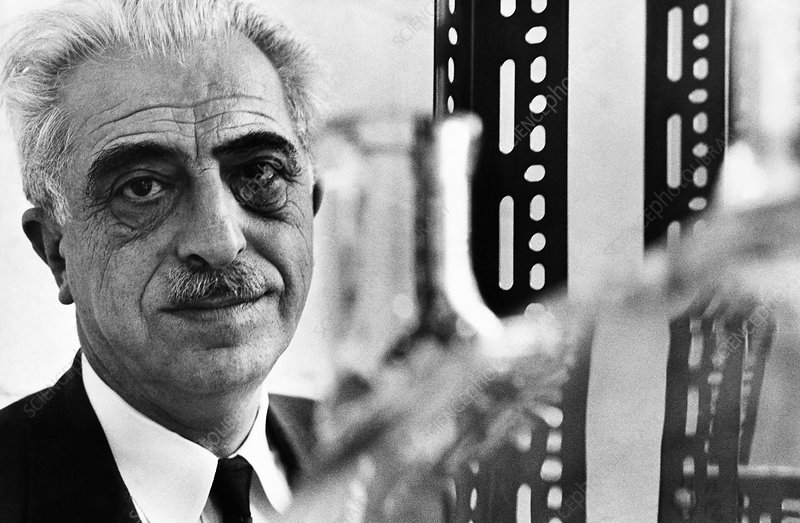

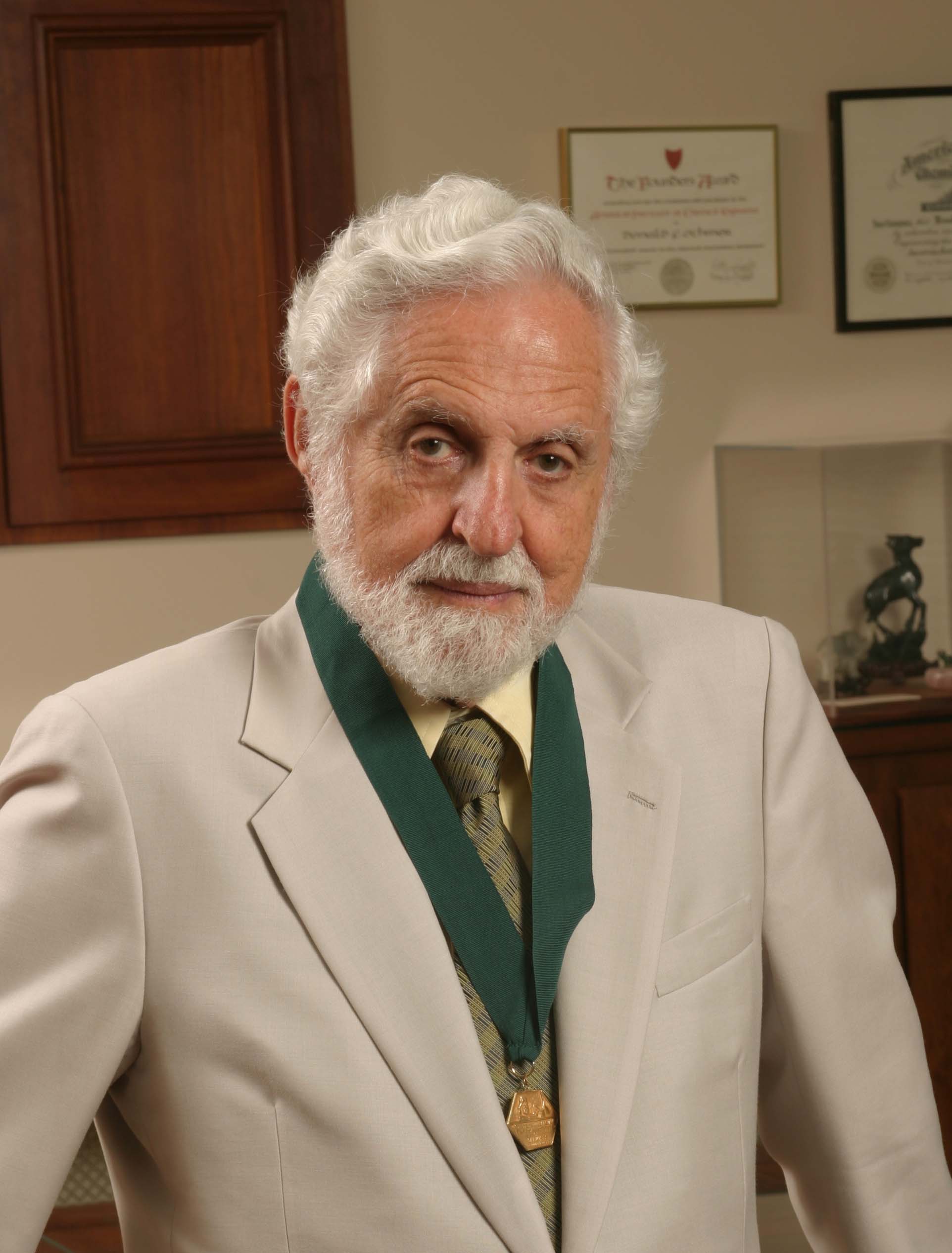

The person who supplied Pincus with the norethisterone for his study was Carl Djerassi, a brilliant researcher who lived in Mexico at the time. Djerassi’s personal story goes well with the narrative of the pill. He was born in Vienna to a Jewish Bulgarian father who specialized in sexually transmitted diseases, and to a Jewish mother who was a dentist and a native of Vienna. After Carl’s parents divorced when he was 15, a ‘system failure’ named Adolf Hitler came to Austria in the form of the Anschluss. The older Djerassi quickly returned to Vienna from Bulgaria and remarried Carl’s mother so he could get them out of Austria.

Carl and his mother traveled from there to the United States. Their possessions amounted to 20 dollars in cash, which were stolen by a taxi driver. But, in the end, America was good to them. After he started high school, the young Carl wrote a letter to the wife of the U.S. President, Elinor Roosevelt, and asked for her assistance so he could go to college. The letter clearly reached the right hands – and the Institute of International Education of the United States awarded him a scholarship. By the time he was 17, Carl was already a college student. And by the time he was 19, he had already obtained a patent on a synthetic antihistamine. He completed his Ph.D. at the age of 23 and moved to Mexico, apparently to get out of a failed marriage. In Mexico, he met George Rosenkranz, a Budapest-born Jew. Rosenkranz, who was educated in Switzerland, had been smuggled to Central America by his mentor, the Nobel Prize winner Leopold Ruzicka – so they would not have to rely on the Swiss authorities if the Nazi surge reached there as well.

It was within the close circle of Hungarian Jews who had fled from Hitler that Rosenkranz met Emeric Somlo shortly after the war ended. Somlo was a wealthy Jew who was in the midst of a crisis: Somlo and his American partner had started a company in Mexico named Syntex, where they extracted hormones from a large-sized Mexican yam called cabeza de negro. But their chief scientist, an American named Russell Marker, ran off and took their secrets with him. The business partners were left without any distinguished scientists in Mexico who could continue the project.

Rosenkranz was hired by Syntex to be their laboratory director and he brought Djerassi along with him. They found a young and brilliant Mexican research assistant named Luis Miramontes, and together they started reconstructing Marker’s work. Their joint efforts paid off in October 1951, when they managed to produce the needed norethisterone. All three of their names appear on the patent they obtained. But, as occurs quite often in the industry, Syntex was not the company that ultimately brought the drug to market, but rather it was other companies that acquired the approvals before they did.

Pincus died of a rare blood disease in Boston in 1967. Rosenkranz, as always, left the ethical and social dilemmas to others. His main objective was to promote industrial development in Mexico, to which he was indebted for taking him in as a refugee. In 2001, he received the prestigious Eduardo Liceaga Medal from the president of Mexico for his contribution to medical science. In 2016, the United States Congress marked his 100th birthday. Rosenkranz died three years later in California, where he lived in his last years.

Yet, a Google search for the “father of the pill” will usually retrieve the name Carl Djerassi, mostly because he took on that role. In the 1970’s, he began devoting most of his efforts to researching and teaching topics that have social implications – and primarily the effect of the birth control pill on the sexual revolution. He also became an important art collector and founded the eminent Djerassi Resident Artists Program, apparently following the suicide of his daughter who was an artist. Committed to the idea that the pill advances gender equality and enables women to plan their professional lives, he also spent a lot of time exploring the possibility of inventing a pill for men. But it turns out that the notion of men taking responsibility was not appealing enough to pharmaceutical companies and scientific organizations. Djerassi died in San Francisco at the age of 91. At least he did not have to watch his America turn the clock back 50 years with the stroke of a single decision of one Supreme Court.