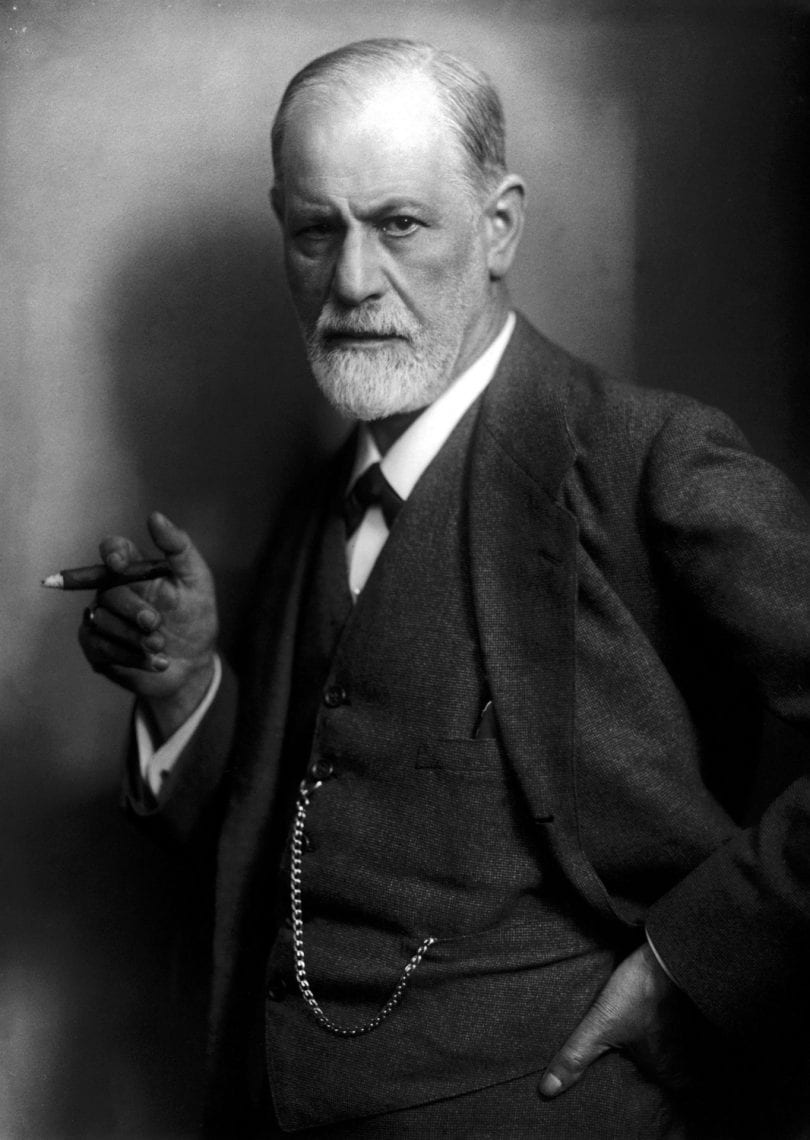

Sigmund Freud, the founding father of psychoanalysis, was first jolted by his Jewish origins when he was six years old. It was a Shabbat in the afternoon when his father, Jacob, went out for a walk on the streets of Vienna, wearing a new fur hat. A Christian boy suddenly approached him and yelled, “Jew, get off the sidewalk” – and knocked his hat into the mud. When Jacob returned home, he told his family about the incident. “And what did you do?’ young Sigmund asked him. “I got off the sidewalk and picked up my hat,” his father answered.

Young Sigmund was outraged by his father’s powerlessness, for standing there humiliated while the Christian bully looked on. A year later, at the age of seven, he walked into his parents’ bedroom, took out his penis and urinated on the floor. Freud’s infuriated father snapped at Amalia, his wife and Sigmund’s mother, claiming that the boy would “never amount to anything!” At this point, it is quite tempting to try and analyze the Oedipal conflict of the man who invented castration anxiety and parricide. But the truth is that the famous urination episode in the bedroom of Freud’s parents, as well as his father’s reaction, were an exception to the rule. Young Sigmund was actually the jewel in the crown of the Freud family.

When Sigmund was still very young, his parents realized that they were raising a rare genius in their home, a bookworm who was proficient in ancient languages, Greek and Latin, and excelled in his studies far beyond any of his classmates. His mother called her son Sigi “my golden boy” (“mein goldener Sigi”) and his father boasted to a family friend that “my Sigmund has more intelligence in his little toe than I have in my whole head.” Freud would later tell people that the confidence he had in his talents derived from the trust placed in him by his family, and especially his mother.

His complex relationship with his Jewish roots would, however, accompany Freud throughout his life. Although his biographers disagree about how religiously devout his parents really were, there is no doubt that Freud, who became an atheist as an adult, came from a home that had a rich and extensive collection of Jewish books. Thanks to his father, Freud knew the Bible well, in addition to Hebrew and key works of Jewish philosophy. Right after the Anschluss in 1938, when the noose around the neck of the psychoanalytic movement in Vienna was tightening, Freud compared himself to Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai, who had demanded from Titus, “Give me Yavne and its sages.” In doing so, he preserved Jewish wisdom following the destruction of the Temple.

On the other hand, Freud had no religion and no nation. “A godless Jew” was the way he defined himself. “I can say that I am as distant from the Jewish religion as I am from all other religions…having said that, I never lost the feeling of belonging to my people, which I always instilled in my children. We were always part of the Jewish community.” That same year, when the winds of antisemitism were blowing strongly in the country of Goethe and Schiller, Freud said: “My language is German. My culture, my attainments, are German. I considered myself German intellectually until I noticed the growth of antisemitic prejudice in Germany and German Austria. Since that time, I prefer to call myself a Jew.”

Before the Nazis rose to power, Freud refrained from analyzing his Jewish identity. In his introduction to the Hebrew translation of Totem and Taboo, he wrote: “I cannot express the Jewish essence clearly in words, but some day, no doubt, it will become accessible to the scientific mind.” So, as surprising as it may sound, the man who determined with such clarity that the human psyche is structured into three parts found it hard to be definitive when it came to his own roots. When eulogizing the psychoanalyst David Eder, Freud wrote: “We were both Jews and knew of each other that we carried in us that miraculous thing in common which – inaccessible to any analyst so far – makes the Jew.”

In his seminal work Freud’s Moses, the historian, Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, wrote that Freud was both intrigued and troubled by his Jewish origins. The father of psychoanalysis believed that the Jewish people had immense spiritual and intellectual qualities, which were an outcome of their special circumstances as an eternal opposition of the nations of the world. “If you do not let your son grow up as a Jew,” Freud wrote to the father of one his patients, “you deprive him of those sources of energy which cannot be replaced by anything else. He will have to struggle as a Jew, and you ought to develop in him all the energy he will need for that struggle.”

You don’t have to be a prominent psychologist to understand that while Freud knew that antisemitism was damaging to the Jews, he also believed that it helped enhance their talents because they were engaged in a constant struggle. He viewed it as a tragic decree of fate that has also advantages. On the other hand, Freud was very concerned that psychoanalysis would be branded a “Jewish science.” He therefore insisted on establishing a close relationship with Carl Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist, who later became his bitter rival. “I surmise that the repressed antisemitism of the Swiss (Jung), from which I am to be spared, has been directed against you in increased force,” he wrote to Sabina Spielrein, Jung’s Jewish lover. “My opinion is that as Jews, if we want to cooperate with other people, we must develop a little masochism and endure a little injustice…”.

In 1934, when Nazism was already an accomplished fact in Germany, Freud felt that enough was enough and that, as a scientist, he was obligated to finally confront the Jewish demons in his soul. To achieve that, he dove into rigorous scientific research that would be the last he would conduct in his lifetime.

Moses and Monotheism was the last important work that Freud wrote before his death. It incorporated historical theories advanced by the Biblical archaeologist, Ernst Sellin, combined with psycho-national analysis which is based on the idea of the murder of the primal father.

According to Freud, Moses was an Egyptian prince, an ardent believer in monotheism, who sought to bring his worldview to an oppressed and rather insignificant people – the Israelites. During their journey in the desert, the Israelites murdered Moses and reverted to their polytheistic pagan practices. “The return of the repressed” surfaced much later in the form of the prophets’ moral teachings, the emergence of Christianity, and later on the rigid theology of Jewish law that evolved while the Jews were in exile. Contrary to Christianity which was founded on the Holy Trinity, the Jews insisted on preserving the monotheistic values of the primal father, Moses Rabbenu. Freud therefore concludes that their religion is much more spiritual and intellectual than Christianity.

Freud’s analysis sparked a lot of criticism, both among Jews and non-Jews. But the old lion was not bothered by it. While witnessing the demise of the magnificent German culture, he fled to England, where in 1939 he returned his soul to his Maker, whom he had not believed in so religiously.

This month, we celebrate the 165th anniversary of the birth of this Jewish genius. You can learn more about his story, as well as the glorious history of German Jewry, at the new exhibition at ANU-The Museum of the Jewish People.