He was sort of the Jewish version of Forrest Gump. He was considered one of the richest and most powerful people in the United States, a man shrouded with international mystery who overthrew governments, orchestrated coups and had government agreements amended to meet his business needs. The reason why you probably never heard his name is because he was obsessive about maintaining his anonymity. The intention is to Sam Zemurray – nicknamed “the banana man” – who built a business empire on his own from scratch and whose persona was a fascinating and unique amalgam of bigger than life figures, such as Howard Hughes and the fictional Great Gatsby.

Zemurray, whose given name at birth was Schmuel Davidovich, was born to a poor Jewish family in Kishinev in 1877. His parents were David and Sarah (née Blausman) Zmurri. At the age of 14, after his father died, Schmuel and other family members emigrated to the United States, where he changed his name to Sam Zemurray.

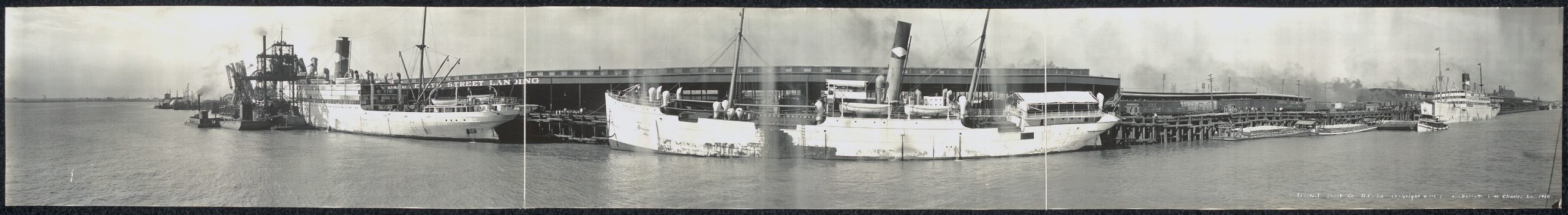

His first successful business venture was in New Orleans, where he took advantage of the fact that traders would throw out newly imported ripe bananas because they feared the fruit would spoil before it came to market. Zemurray would go to the wharf and meet the ships from Central and South America that were carrying bananas which had ripened en route and were going to be discarded. He would buy the bananas at rock-bottom prices and sell them to peddlers located near the train station and along the railway track from New Orleans to Selma, Alabama, where he lived with his family. Within about three years, when he was only 21, “the banana man” had already made $100,000. “When I was eighteen, I walked into the jungle, and when I was twenty-one, I walked out. And by god I was rich!” – he is quoted as saying in his later years. His meteoric success enabled Zemurray to purchase land in Honduras, where he began growing bananas of his own. He would then bring the bananas to the United States on ships that he had also bought.

In 1930, Zemurray sold his business (Cuyamel Fruit Company) to the produce giant, United Fruit, for more than $30 million. After United Fruit ran into difficulties during the Great Depression, they approached Zemurray and asked him to take charge and rescue the business. When Zemurray came to his first board meeting and met the company’s management, all graduates of the most prestigious universities and an arrogant bunch who were infected by the antisemitism prevalent at the time (when Zemurray wanted to buy a house in Boston, the owners refused to sell it him because he was Jewish), they made fun of his accent. “We don’t understand a single word you’re saying,” they said scornfully. Not long after that Zemurray went back into the boardroom and shot in all directions: “Let’s see if you understand this – you’re all fired!”

Among other things, the rapid rise in Zemurray’s financial fortunes can be attributed to the tax concessions he received from the Honduran government. But all that was about to change when the government of Honduras had to reschedule its external debt and agents of the U.S. government were sent there to collect taxes to repay the debt. The new taxes threatened to ruin Zemurray’s business operations, but he was not about to give up his life’s work so easily. He therefore made contact with the ousted president of Honduras, Manuel Bonilla, who was living in exile in New Orleans. Together with some mercenaries, they planned a military coup that ended in success. Zemurray got back on the horse and once again received tax concessions that saved his business.

During his tenure as president of United Fruit, the company had over 100,000 employees and its assets included 75% of the private land in Guatemala and Honduras. The company had a fleet numbering more than 60 cargo ships, as well as its own home ports in northern Honduras, Puerto Cortés and New Orleans. United Fruit also owned its own rail lines as well as postal and telephone services in Central American countries.

In World War II, Zemurray lost his only son, Sam Junior, who was a pilot in the U.S. Air Force and was shot down in Algeria. The devastated Zemurray found solace in his friendship with Chaim Weizmann, whose younger son, Michael Oser, was also a pilot who was killed while serving in the Royal Air Force just one month before Sam Junior’s death. Weizmann and Zemurray first met in 1922 when Weizmann came to the United States to raise money and support for the Jewish Agency. After that, whenever the future first president of the independent State of Israel would come to the United States, the two would get together.

Due to his identification with the early Zionists, Jews from Eastern Europe like himself who had taken control of their destiny, Zemurray supported them as much as he could. He donated $500,000 to the Jewish Agency, hundreds of thousands of dollars to the establishment of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the establishment of the Daniel Sieff Research Institute (which later became the Weizmann Institute of Science), $700,000 for building a power station in Palestine, and served as a director of the Palestine Economic Corporation. In his autobiography Trial and Error, Chaim Weizmann wrote the following about Zemurray: “It was said of him that his success in the Central American republics was mainly due to the fact that he was deeply concerned for the welfare of the peons he employed – which was by no means the case with most of his competitors. He built schools, hospitals, recreation grounds and model villages.”

His friendship with Weizmann touched a chord with Zemurray’s Jewish roots and he became actively involved in doing good for his people. It started with Aliyah Bet – the clandestine operation that brought Jews to Palestine during the British Mandate. As noted above, Zemurray was in possession of a fleet of cargo ships. Because some of them were equipped with good ventilation systems, they could easily be converted into passenger ships. Sam Zemurray’s Russian-Jewish roots were an excellent foundation for the ties that the Aliyah Bet activists forged with the Jewish “banana king.”

In his book The Jews’ Secret Fleet, Murray Greenfield describes how between 1946 and 1948 about ten ships for transporting illegal immigrants were bought in the United States, whose crew members included around 250 volunteers. Zemurray and his people were involved in buying all the ships and in recruiting the volunteers. According to estimates, each one of those ships brought around 7,500 illegal immigrants from ports in Bulgaria and Romania to pre-State Israel.

Zemurray’s Zionist activities were not confined to Aliyah Bet. One of the seminal events he played a key role in was the vote held in the United Nations on November 29, 1947, surrounding which his behind-the-scenes efforts helped determine the outcome. At Weizmann’s request, Zemurray took advantage of his far-reaching connections in Latin America and exerted all his influence to persuade the governments there to vote in favor of the Partition Plan for Palestine.

According to Weizmann, on the evening in question Zemurray sat down, picked up the phone and “went to work.” He asked every leader in Central America two questions: How do you intend to vote on partition? And, can your vote be changed? After making the round of phone calls, Zemurray told Weizmann that every vote from Mexico to Colombia was up for sale, but the price was very high. By the time the votes were actually counted, all the Central American countries had switched their votes to “yes” – with the exception of Honduras, which abstained due to pressure from the Arab community. Zemurray summed up the vote by saying: “You can’t get anything without fighting for it.”

Zemurray continued to devote his time and energy to the State of Israel following its declaration as well. His contribution was primarily felt during the War of Independence, when he used his fleet of ships to evade the embargo and smuggle arms and food into the young country.

Sam Zemurray died of Parkinson’s disease in New Orleans at the age of 84. The biography that was written about him, published in 2012, was entitled: The Fish That Ate the Whale.

You can also find Sam Zemurray in the new exhibition spaces at ANU-Museum of the Jewish People, whose story appears in the American Jewry section