During the second season of Israel’s “Master Chef,” contenders were asked to cook a meal for someone close to their heart. One of them, Emanuel Rosenzweig, dedicated his meal to his grandfather Franz Rosenzweig, the renowned philosopher whom he sadly never had the privilege to meet. The studio fell silent. The judges – whose menus rarely feature spiritual sustenance – exchanged awkward glances. “Who is Franz Rosenzweig?” they wondered. The other competitors looked at Emanuel with inquiring eyes. Chances are the viewers at home also lacked a clue as to who he was.

It is truly hard to imagine anything further from thinker Franz Rosenzweig’s world than a reality cooking show. Rosenzweig – who openly doubted the Zionist idea – would surely consider it a confirmation of his suspicions. “There it is, just as I predicted,” he would rebuke. The Zionist ambition to produce a model Jew has gone up in smoke in the skillets of prime-time gluttons. The Jews sold their Judaism to be like all the other nations. Such a shame.

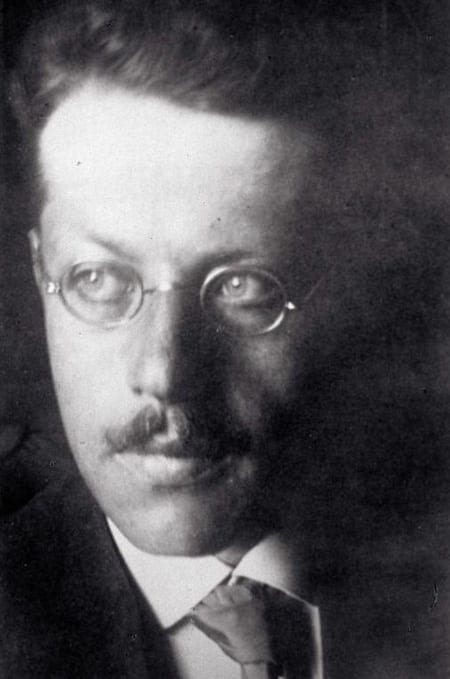

Franz was born 133 years ago in 1886 to a well-to-do paint merchant named George Rosenzweig and his wife Adela. The Rosenzweig home in Kassel, Germany epitomized that of a semi-assimilated Jewish family. Young Franz was raised on the lap of haute European culture. From an early age, he read Goethe, listened to Beethoven, and quoted The Song of the Nibelungs. The late-19th-century German-Jewish ideal of being “more German than the Germans” was first and foremost in the Rosenzweig household. The Rosenzweigs encountered their Jewish identity thrice yearly – on Rosh Hashana, Pesach, and Yom Kippur. Despite that, his parents – and particularly his mother Adela – took pains to maintain a minimal Jewish awareness in their home. Like survivors of a sinking ship, they clung to floating boards in the stormy waters knowing they could lose their grip in an instant and sink to the bottom of the European seas. Yet despite that, they held on.

Franz’s uncle, Adam Rosenzweig, also played a pivotal role in shaping his Jewish identity, giving him what he called a glimpse of the Jewish world and helping him approach it. On the eve of his first day of elementary school, his uncle told him, “My boy you are going among people for the first time today; remember as long as you live that you are a Jew.”

But as years passed, his uncle’s commandment was forgotten. In 1907, after two years of dabbling in the medical education that his father wished for him, natural selection had its way. Then-21-year-old Rosenzweig enrolled in philosophy and history studies at the University of Freiburg, and later studied in Berlin. He fell in love at first sight with philosophy and five years later, published a two-volume doctorate entitled, “Hegel and the State,” examining German philosopher Friedrich Hegel’s profound influence on the modern era. During these years, he devoted himself entirely to a life of learning and his reputation quickly preceded him as an author of brilliant ideas and original thinker with a deeply religious soul.

The year 1913 was considered pivotal in Rosenzweig’s biography. During that year, he declared his inner commitment to a religious life from that day forward. Because he believed Judaism to be the ideal and Christianity to be its concrete expression in reality, he chose to be baptized in a Protestant church.

It must be said that Rosenzweig’s decision to convert to Christianity did not derive from the practical considerations that drove many German-Jewish intellectuals to do the same at the time. Rosenzweig was a religious man who relied on intellectual tools to analyze his religiosity. An examination of his works – including his opus vitae “The Star of Redemption” – reveals a rare combination of outstanding intellect, uncompromising honesty, and fully-developed spirituality. This was at the core of his decision to convert to Christianity.

Young Franz’s conversion broke his mother’s heart. His mother rejected his plan to spend the High Holidays that year with his family in Kassel. “Did you come to mock us before joining the goyim?” she admonished. Dejected and alone, Rosenzweig remained in Berlin entertaining suicidal thoughts. That turning point in his life was the background for the rocking religious experience that returned him to the bosom of Judaism. The 27-year old wandered the streets of Berlin during Yom Kippur that year until he stumbled upon a Neila service in a Hasidic shteibel on the outskirts of the city. It isn’t exactly clear what took place there, but the religious experience that burst forth within him among those hasidim led Rosenzweig to reverse his decision and return to Judaism. Ten days later, he wrote a friend, “I need not convert.” This was apparently how a philosopher taught to repress his feelings chose to express this emotional outburst.

Rosenzweig took his return to Judaism with utmost seriousness. While stationed in the Balkans in the German army in World War I, he met for the first time the Eastern-European Jews in Germany known as “Haustjuden.” Enchanted by their simple, self-assured Judaism, he sat down to write “The Star of Redemption,” in which he outlined three pillars of Judaism that express its entirety: God, the Universe, and the Human Being. He later moved to Frankfurt where he established the “Freies Judisches Lehrhaus (Jewish House of Free Study),” an intellectual warehouse for Jewish spiritual giants like kabbalist Gershom Scholem and philosopher Martin Buber.

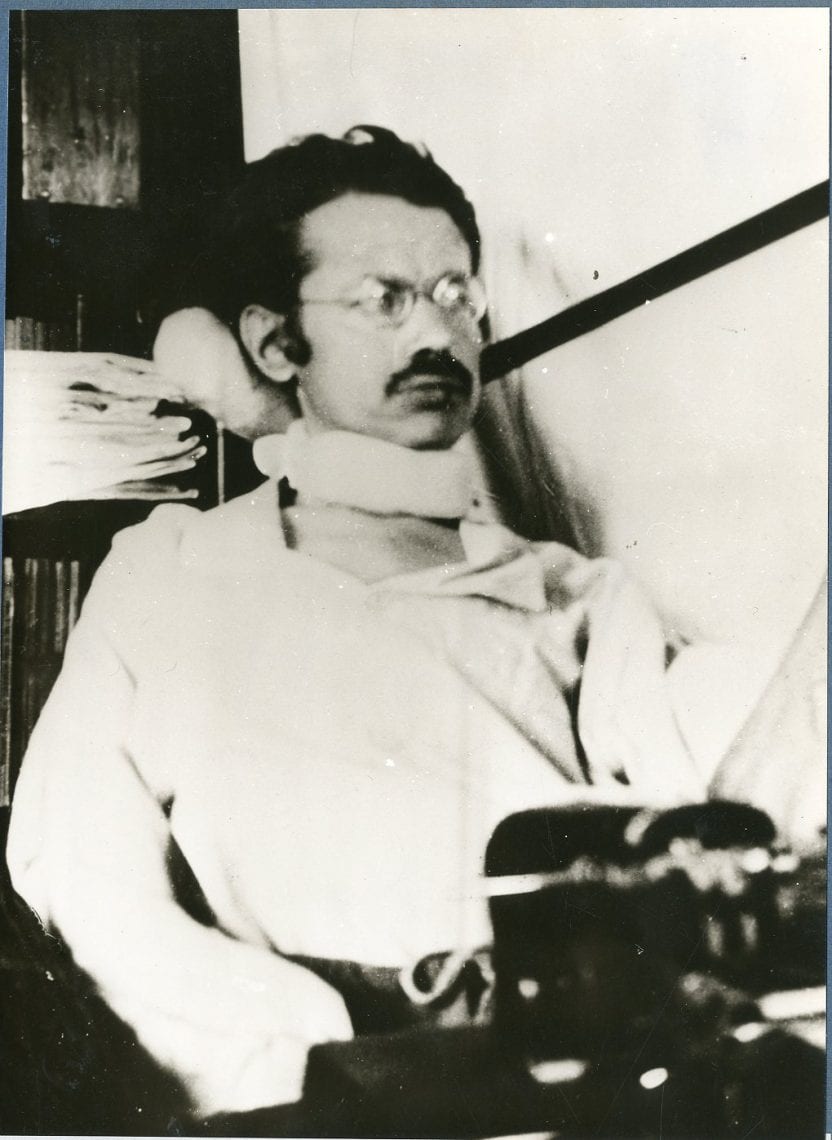

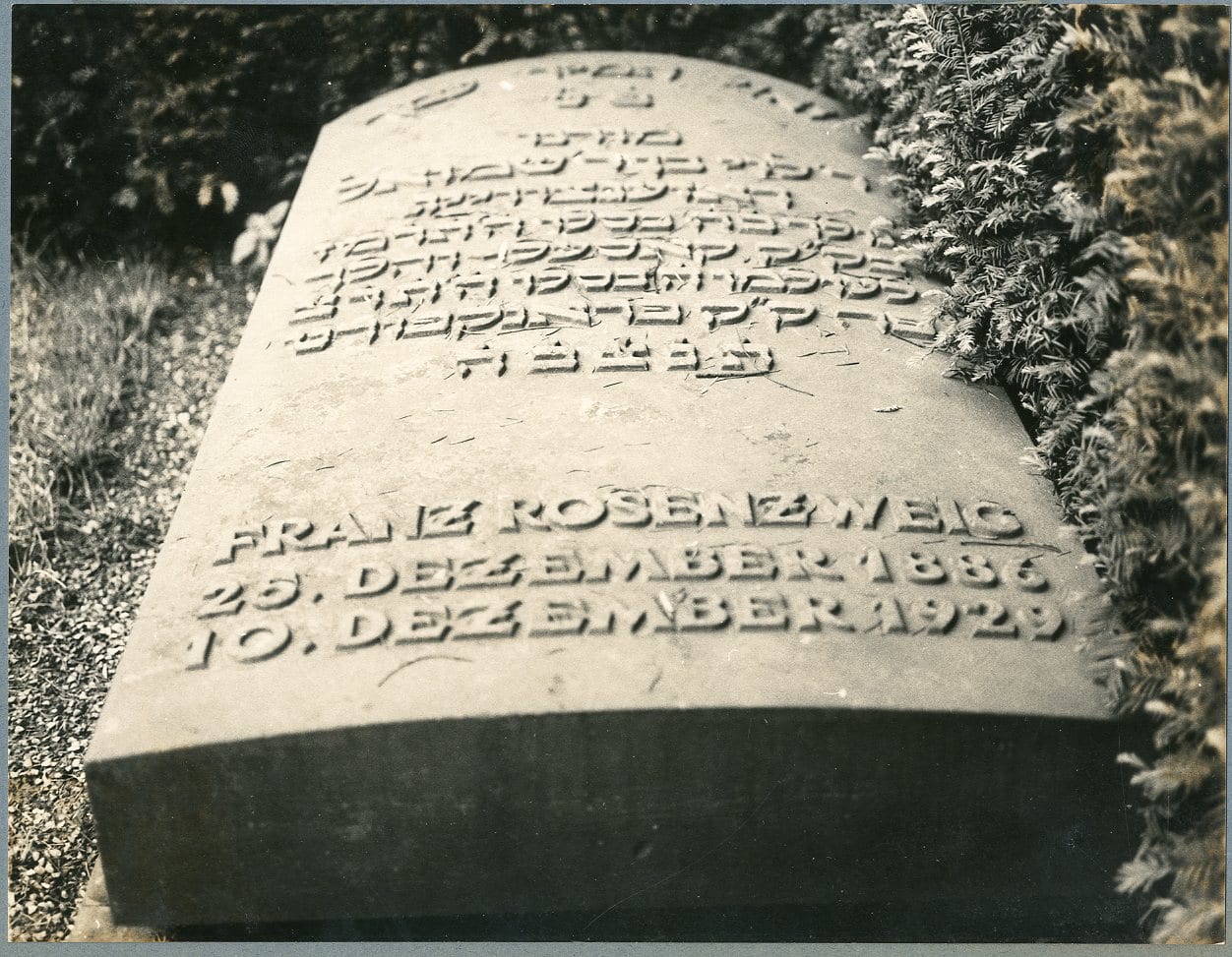

Rosenzweig’s life ended tragically. He contracted severe muscular dystrophy in 1922 and suffered for years as his health deteriorated. Despite that, he did not stop and even ramped up his involvement in various projects. Among them was a translation with his friend Martin Buber of the Tanach into German finished days before his death, while he was completely paralyzed and could only communicate by moving his eyes. Habima Theater star Hanna Rubina visited him on the eve of his death when he was only 43, comforting him moments before he breathed his final death. When Sigmund Freud heard of his death, he said, “The man had no other choice.” That terse comment enfolds within it the entire meaning of the extraordinary character that was Franz Rosenzweig.

Translation from Hebrew: Varda Spiegel