This week 75 years ago, on January 13, 1948, marks the anniversary of the murder of the renowned Soviet-Yiddish actor and director, Solomon (Shloyme) Mikhoels, who was also the artistic director of the Moscow State Jewish Theatre – GOSET. He was also the undisputed leader of Soviet Jewry in those days. The decision to murder him was made by Stalin himself. The reason: the reaction of Soviet Jews to the decision of the Soviet authorities to support the establishment of the State of Israel a couple of months earlier, on November 29th.

According to the official account, Mikhoels was killed in a “hit and run” accident while on a business trip in Minsk. What actually happened was that Mikhoels and his colleague were on their way to dinner at the home of a friend. They got into the car that was sent to pick them up, but were driven to another location outside the city. They were executed there, and their bodies, which showed signs of being run over by a truck, were later placed in an alley.

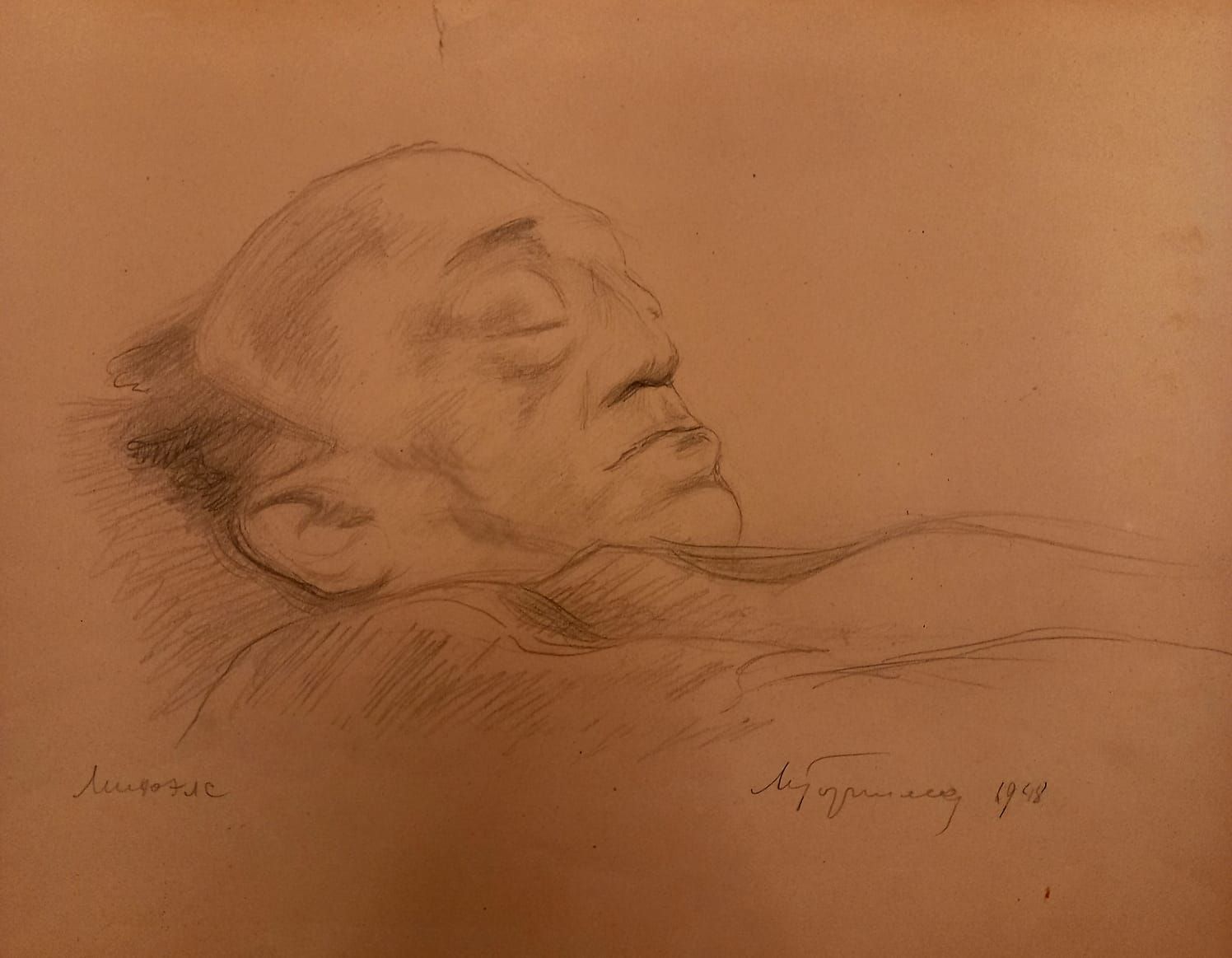

After Mikhoels’ body was brought back to Moscow, Stalin made sure to organize an impressive state funeral for him because he was one of the leading, most prominent and most popular people in the country’s cultural scene. But somewhere in the dungeons of the KGB, Stalin had already set in motion what he hoped would be the demise of Soviet Jewry.

According to the official position of the Kremlin, Soviet Jews had no need for, nor any interest in, another independent country as they ostensibly enjoyed equal rights and did not experience antisemitism like in Western nations. But official positions are one thing, and actions are another. Shortly after the famous meeting between Golda Meir and members of the Jewish community in Moscow on Rosh Hashanah in 1948, Stalin ordered the dissolution of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (which was headed by Mikhoels prior to his murder). He also ordered the arrest of the committee members, who were accused of spying for the West, cosmopolitanism, and planning to establish an independent Jewish republic in the Crimean Peninsula. Following their high-profile trial, the committee members were sentenced to death.

On January 13, 1953, Pravda and other newspapers published a front-page article that began with the following announcement: “Evil murderers and spies are hiding under the masks of the professors and doctors who planned on killing the leaders of the Soviet Union and senior army officers by using medical techniques to poison them.” The accusation was leveled against nine doctors, six of whom were Jewish, including Professor Miron Vovsi, Stalin’s personal physician, Dr. Feldman, Dr. Etinger, Dr. Meirov, Dr. Grinshtein, and two doctors named Kogan. The anonymous author of the article underscored the Jewish background of those involved: “Most of the members of the terrorist cell were recruited by the U.S. intelligence services and an international bourgeoise-nationalist Jewish organization called the Joint, which is a Zionist espionage organization that hides under a philanthropic guise.” The article, which was published five years to the day after Mikhoels’ murder, depicted him as a “well-known Jewish-bourgeoise nationalist.” According to the article, Mikhoels was the one who had made the initial contact between the Joint and the accused, and in particular Prof. Vovsi who was his second cousin.

Prof. Vovsi was an internist, a member of the academy and an award-winning specialist in his field. With those credentials, he was ‘perfect’ for heading the conspiracy of the “doctors in white coats” – which is how the accused were referred to. Vovsi had been Stalin’s personal physician for years, and was one the senior consultants at Kremlin Hospital, where he treated all the top brass of the government.

Miron Vovsi was born in a small village in the Vitebsk province in May 1897. His father, Shimon, and his older brother, Boris, were murdered by the Nazis in 1941 together with all the Jews in the village. Vovsi had dreamt of becoming a physicist or a mathematician, but as a Jew it was next to impossible to be accepted to those schools. The requirements for medical studies were not as stringent. He began studying medicine at the university, but was forced to stop following the outbreak of World War I. After completing his studies in 1919, Vovsi enlisted in the Red Army as a military doctor. His academic career began in 1922, which included specializing in internal medicine and conducting biomedical research.

In 1927, Vovsi was sent to Germany for an advanced residency. Back then, Germany was at the forefront of state-of-the-art medicine. In 1935, he was appointed Chair of Internal Diseases at the main doctors’ training institute, as well as head of the Internal Medicine Department at Botkin Clinical Hospital in Moscow, which at the time was one of the most renowned and leading-edge hospitals. Vovsi’s rise to fame was meteoric thanks to his precise diagnostic skills and ability to find proper treatments very quickly. His success also stemmed from the pleasant and attentive care he gave to all those who approached him. Thus, in addition to his work in research, he also joined the staff of consultants at Kremlin Hospital.

Throughout his career, Prof. Vovsi did research on vital internal organs, the vascular system and metabolic disorders. In 1938, he developed a treatment for pneumonia using a serum, and also improved the diagnostic and clinical protocols for kidney failure and angina.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, Vovsi became the chief physician of the Red Army, receiving the rank of Brigadier General in the Medical Corps. After the war ended, he continued his work as a researcher, diagnostician and clinician at Botkin Hospital and Kremlin Hospital.

Stalin’s health began to deteriorate at the beginning of the 1950’s. His paranoia attacks became more frequent, and the only doctor that was allowed to get close to him was Prof. Vovsi. Furthermore, Stalin demanded to be involved in everything that was going on in the country, especially the purges. After World War II ended, Stalin slowed the pace of the political executions, chose the timing of all the show trials, and made sure they were based on earlier events. Thus, after the members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee who had been accused of espionage were executed in August 1952, Prof. Vovsi was arrested at the end of that year. Following the torture he was subjected to, he ‘confessed’ that as a secret agent of the American and Zionist intelligence services he had intentionally shortened the lives of his famous patients by prescribing the wrong treatment to them.

After the Doctors’ Plot became known to the public, many hospitals held large-scale gatherings where the accused were condemned. Jews, doctors, and other people became immediate suspects capable of causing harm to the state and its citizens at any given moment. The newspapers published vilifying caricatures and articles that called for severely punishing “the murderers in white coats.” They were also in favor of executing them.

The Doctors’ Plot received a lot of attention in the Western world, attributed, among other things, to the alleged involvement of the Joint. On February 11, 1953, the State of Israel reacted by severing diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. David Ben-Gurion also tried to outlaw the Israeli Communist Party (Maki) and even imprison its leaders.

On the night of March 1, 1953, Stalin had a stroke due to a brain hemorrhage. His guards found him lying unconscious on the floor in one of the rooms in his vacation home. According to reports, for hours no one dared to touch the leader for fear of being accused of killing him. So the revered generalissimo, who had sent millions to their deaths in a matter of days, continued to lie on the floor, drowning in his own body fluids until he finally died on the morning of March 5, 1953.

Just one month after Stalin’s death, Moscow issued an official statement saying that the doctors accused in the plot had been released because they were found innocent. As for Prof. Vovsi, even though his health had been compromised because of the torture in prison, he returned to his scientific and clinical work, which he continued to engage in until he died in June 1960.

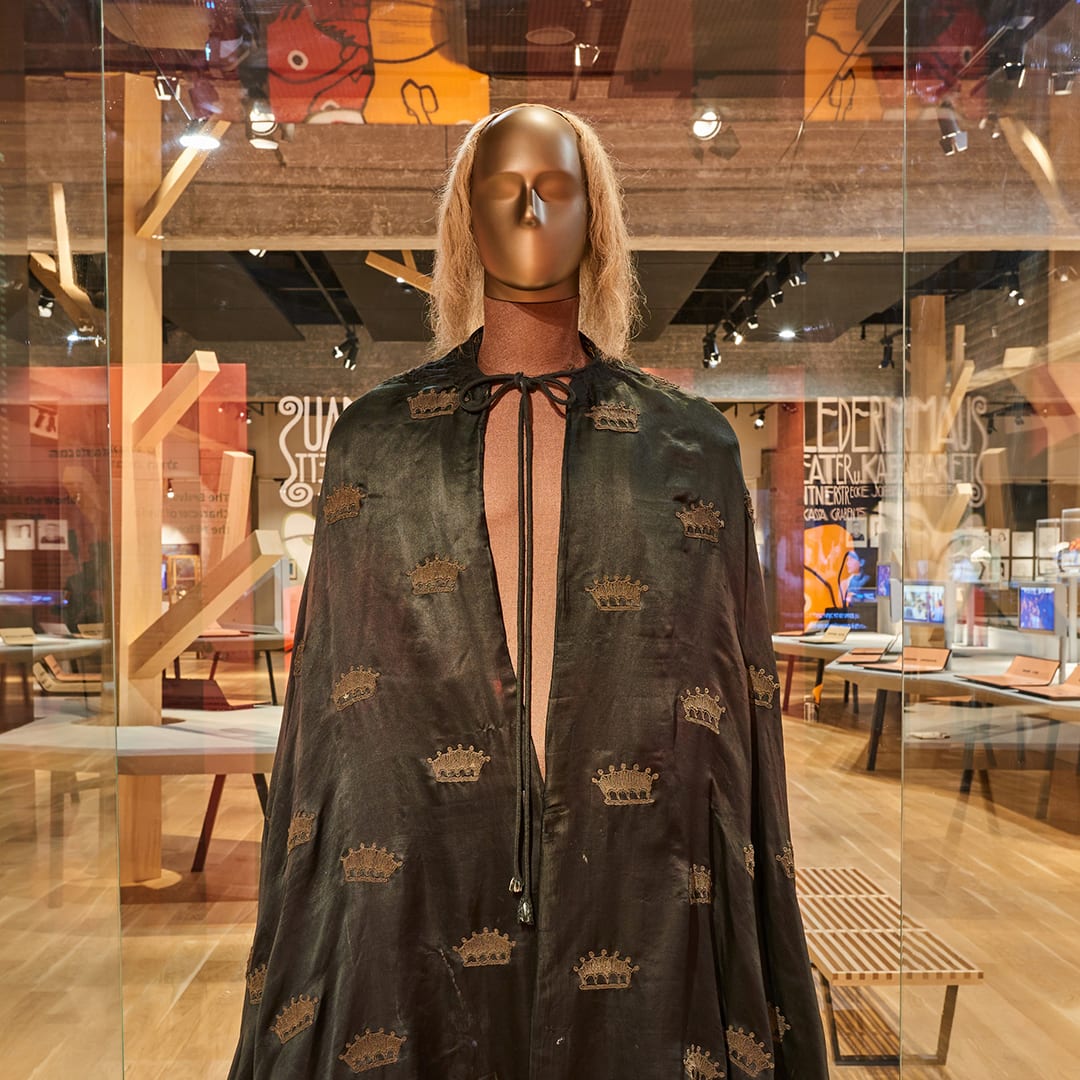

An international cultural center in Moscow is named after Mikhoels, as are streets in various cities all across Russia. In Israel, a city square in Tel Aviv close to Habima Theater is named after him, as well as streets in Rishon LeZion, Petach Tikva and Haifa. The robe and wig worn by Mikhoels when he played King Lear in Moscow are on display in the theater exhibit on the third floor of ANU-Museum of the Jewish People. In a special audio guide produced for the new museum, Lea Koenig, the first lady of Israeli theater, who also portrayed King Lear in the past, says the following: “In some ways, all of us, actors and creators of Jewish theater in Israel and around the world, have emerged from the folds of this cloak once worn by Mikhoels.”