The stage and cinematic history of The Megile written by the acclaimed Yiddish poet and playwright, Itzik Manger, is quite long. But in line with accepted practice, it’s worth starting from the beginning. Manger was born in 1901 in Czernowitz, the capital of Bukovina – a region that links Romania and Ukraine – which today is part of Ukraine. Following the outbreak of the First World War, Manger fled to Romania. As a young man, he lived in Bucharest and Warsaw, as well as other places. After the Nazis rose to power, he fled once again, and this time to Paris, and after that to London. And like many other Yiddish writers, he eventually settled in New York.

His first book of poems was published in Bucharest in 1929, and Megile-lider (Megillah Songs), the matter at hand here, was published in Warsaw in 1936. In that anthology of poems, Manger relocates the story told in the Book of Esther from ancient Persia to Eastern Europe of the early 20th century. It was not the first time he did something like that. In Khumesh-lider (Bible Songs), an earlier work by Manger, he portrayed Abraham, Isaac and Jacob as shtetl characters.

In his writing, Manger combined provincialism and modernism, while remaining keenly aware of the suffering of his fellow European Jews. And how did he convey that suffering? Using humor, of course. Among other things, he found humor in Biblical narratives, which he adapted to the time and place he was familiar with – with the result being a satire sanctioned by Jewish sources.

“In those poems, there was a winning blend of humor, provincialism and lyricism, as well as a clever mixture of ancient Talmudic and literary traditions with the living tradition of the Purim spiel, which expanded on the Book of Esther story and added new characters and plots to it.” That is how the poems were described on Xargol Books’ website, which published a new bilingual edition of Megile-lider in Yiddish and Hebrew in 2010 – with a translation and notes by David Assaf and illustrations by Noam Nadav, both of whom were huge Manger fans.

As mentioned above, Manger added characters who were not in the original text (in his preface, he joked that they had been deleted from the original Megillah because of their inferior social status): two commoners, tailors, like Manger’s own father. One was a young tailor named Fastrigosse, who was in love with Esther, and the other one was an old and pious tailor, named Fanfosso. In Manger’s version, Esther cries over the ashen-faced tailor’s apprentice, whom she left in order to marry the king and enjoy a life of comfort. Her jolted sweetheart threatens to kill himself and sets out on a journey, while she continues to agonize. What stands out in the story is the yearning, which was, of course, the lot of all European Jews in the years between the two world wars.

And the poems then went from book to stage. At the end of the 1930’s, they were dramatized by Zvi Bauminger for the Hashomer Hatzair leadership in Lvov. Whereas in Israel in the 1960’s, they turned them into a musical comedy. The latter was an initiative of Shmuel Bunim, a great admirer of Manger who had also directed an adaptation of his book Dos Bukh fun Gan-Eden (The Book of Paradise) at the Cameri Theater. Bunim turned Megile-lider into a Purim spiel – an amusing skit based on the Book of Esther. Purim spiels were a popular genre in Europe that started in the 16th century. Bunim contacted Manger during a visit in Israel, and Manger approved the idea. Bunim made Megile-lider into a Yiddish play, and Dov Seltzer composed the original music for it.

Bunim cast the Burstein family in the lead roles. The Four Bursteins were a troupe of actors who appeared in New York’s Yiddish theater. The quartet was comprised of Pesach Burstein (who was also the son of a tailor), who had emigrated to the United States, his wife, Lillian Luks, and their two twins, who began performing on stage at an early age and were known by their stage names, Motele and Zisele. Motele was none other than Mike Burstyn. After Mike’s sister left show business and the remaining three Bursteins came to Israel to put on a play, Bunim cast them for his musical.

The Yiddish musical was not an instant box office success. But after the critic Haim Gamzu sang its praises, it became a huge hit even among Israelis who were not Yiddish speakers. It was put on 250 times in its original venue, the Hamam Club in Jaffa, and also on other stages countrywide. In 1965, the soundtrack was made into a record album. Bunim also took the play to Broadway and to other places around the world. In October 1968, Tamar Avidar reported in Maariv that “the first Israeli director to direct a play on Broadway – Shmuel Bunim – hurried back to Israel on Saturday night after the premiere of The Megile, and the excellent reviews have followed him from there. The success of The Megile of Itzik Manger – whose rendition is nearly identical to the one that was staged in Israel – is greater than what the optimists envisioned in their wildest dreams.” The Bursteins also starred in the play in the United States, where the entire play was performed in Yiddish apart from some narration in English.

Later on, in the 1970’s, the play was broadcast on Israeli television, with Gadi Yagil cast as the young and romantic tailor, Avraham Mor as Ahasuerus, Shmulik Segal as Mordecai, Nira Rabinovich as Vashti and Zeresh, and the young Efrat Lavie as Esther. The television broadcast of The Megile in Yiddish (with Hebrew subtitles) was an indication that people still wanted to underscore the contribution of Yiddish works to Israeli culture.

The first thing that comes up when you Google Itzik Manger’s The Megile is a picture of the late Avraham Mor with a crown on his head, hanging a festive sign written in a Serif font (the one with the tiny projections): “The Megile, the Folk Opera by Itzik Manger, Starring Purim Spiel Actors” – including a distinguished list of credits. On Kan 11’s official YouTube channel, you can watch the entire nostalgic Purim spiel, which was broadcast by the Israel Broadcasting Authority in 1976.

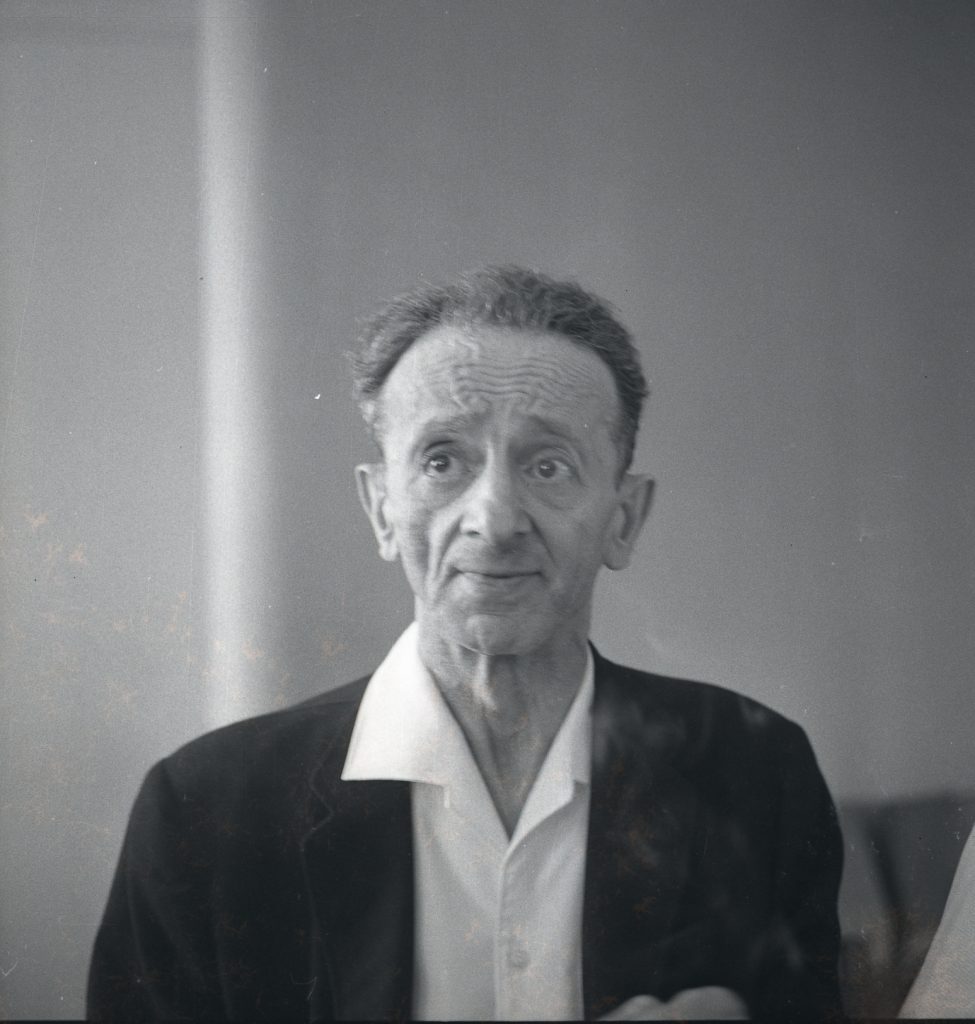

Manger, who was already sick at the time, immigrated to Israel in 1966. The reason, as he told his friend Shalom Rosenfeld, was the thought that no one would come to his funeral if it were in the United States. He died in Israel three years later, in February 1969. He had an impressive funeral at the Nahalat Yitzhak cemetery, attended by the President of Israel, Zalman Shazar, the Minister of Education, Zalman Arad, the Mayor of Tel Aviv, Mordechai Namir, and thousands upon thousands of mourners. The fact that he came to Israel to die was significant to his legacy and the legacy of Yiddish culture in Israel. For years, the Itzik Manger Prize for outstanding contributions to Yiddish Literature was awarded to different people. Shmuel Bunim and Dov Seltzer received it in 1985, and Pesach Burstein received it the following year, less than two months before his death.

The Megile also received a Hebrew version that was written by Haim Hefer and staged at the Bimot Theater and Yuval Theater. It, too, was filmed for television, starring the immortal Avraham Mor alongside Sassi Keshet, Sarai Tzuriel, Yankele Ben Sira, Osnat Vishinsky, and others. Additional Yiddish versions were produced over the years. In 1988, a year after the Yiddishpiel – Yiddish Theater opened in Tel Aviv, The Megile was staged there for the first time, starring Yankele Alperin, Jonathan Sagall and other actors. In 2010, Yiddishpiel put it on again, with Yaakov Bodo in the leading role, and seven years later it was staged there a third time.

All of this makes sense and was even expected. What makes less sense is the movie, The Megillah 83. The same Jonathan Sagall, who played Fastrigosse at the Yiddishpiel, also portrayed him on the big screen in that odd Israeli-German co-production directed by Ilan Eldad, with Nitza Saul in the role of Esther, Aviva Paz as Vashti, and none other than Shlomo Bar-Aba as the evil Haman. In the film, the actors speak Yiddish, whereas the narrator speaks German (a version with an English-speaking narrator was also produced). So, it’s not surprising that the result was an especially cringey and bizarre farce.