Though Gnosticism was introduced in the Mediterranean basin 2000 years ago, splitting the world into the kingdom of good and the kingdom of evil, one 20th century man, a one-time Jewish genius personified this dualism in the most extreme, almost incomprehensible manner.

On the one hand, there was Dr. Fritz, laureate of the Nobel prize in chemistry, the scientist who picked “Bread from the Air” after discovering how to synthesize ammonia from nitrogen, thus saving the world from famine. Then on the other hand there was Mr. Haber, the scientist whose name is directly associated with the first use of chemical weapon in the history of mankind, and whose research was foundation for the development of Cyclone B, the toxic gas that liquidated some million and half of Haber’s fellow Jews in the Nazi gas chambers.

Who was that brilliant, complex chemist, described by his associates as impulsive, hot tempered, sharp, a gifted orator, and a hearty interlocutor on various issues?

Fritz Haber was born in 1868 to a well to do merchant of dyes and chemicals from Breslau, now Wrocław in Poland. He studied chemistry in the University of Berlin, graduating as a doctor in chemistry in 1894. At a certain point he realized he could not break the glass ceiling unless he converted to Christianity, like so many other German Jewish intellectuals who truly believed that as long as they define themselves as German patriots, Germany shall embrace them. However as hard as they wished to become Germany’s flesh and blood, their homeland rejected them.

Haber’s career skyrocketed. In 1906 he was appointed professor of physical chemistry in the technical university of Karlsruhe. In 1910 – head of the institute for physical chemistry, as well as professor in Berlin University, and senior member of the Prussian Sciences Academy, the most prestigious institute in Germany. His 15,000 marks per month salary was the highest wage a scientist could then possibly earn.

But it wasn’t just a bed or roses. Though Haber’s life was filled with peaks and achievements, he also knew his share of low points and tragedies that kept knocking on his door (a most fancy door of an extravagant home in the Dahlem quarter in Berlin). His wife Clara, a converted Jew like himself, took her own life in front of their son, Hermann, after she learnt that Haber’s invention of manufacturing weapon from chlorine caused the inhuman death of thousands of French soldiers from suffocation during the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium. His son too took his life later on.

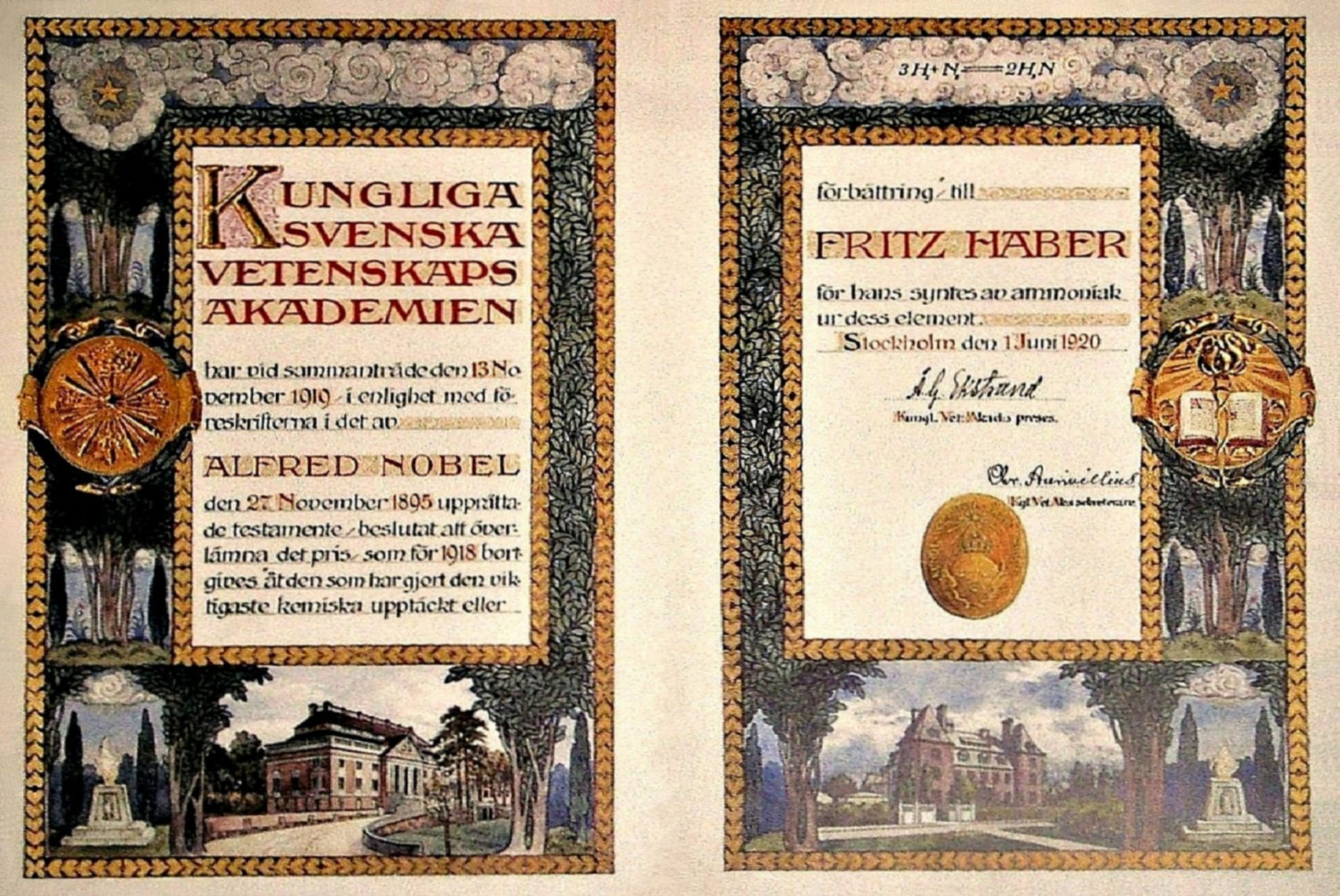

Whether just a strong man, or, as some said, an insensitive heartless fellow, Haber carried on, and in 1918 he won the Nobel Prize for chemistry. The committee explained that Haber’s discoveries were of “the greatest benefit to mankind”. They referred to the process as “making bread of the air”. However, his winning spurred much controversy and public protest. Many scientists expressed their resentment at the decision, and said Haber was in fact a war criminal who developed chemical weapon, for which he had to be locked down, not be honored with the highest prize. The day after the awards ceremony, the press stated that Haber both suffocated thousands to death, as well as saved millions from starvation.

After the war, in the Weimar pre Nazi republic, Haber was a highly respected patriot, a famous scientist and administrator, as well as politician and head of one of the highest titles: Geheimrat (imperial advisor).

But then the Nazis rose to power, and his life turned upside down. After dedicating himself to his beloved homeland, Haber was forced to dismiss all his Jewish employees from the Keiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry in Berlin – and then forced to resign himself. Later he was forced to escape Germany. The racist laws of Nazi Germany allowed no exceptions, not even in regards to his impressive contribution as father of chemical warfare during World War I.

Despite of his famous quote: “In peace-time the scientist belongs to humanity, in war-time to his fatherland.”, the Nazi regime was indifferent. The Jewish scientist who insisted on supervising personally the chemical experiments in the battle fields, and to closely observe his discoveries in killing people, did not earn any credit as a hero. The firm belief of Jews of Germany, that the Germans would not expel them, especially if the Jews deny their Jewishness, was shattered. The Germans expelled, persecuted, and later also eliminated them – using Haber’s scientific discoveries.

For months, the rejected, hurt lover wandered throughout Europe: Switzerland, France, Spain and Britain, yet failed to find an academic position. Haber, who enjoyed world reputation, was now unemployed, tired and sad, begging and pleading.

Ironically, the man who tried so hard to deny his Jewish identity, found some help and hope among his fellow Jews. One of them, another Jewish chemist called Chaim Weizmann, offered to appoint him head of the Sieff institution in Rechovot (the future Weizmann institute). Imagine what he must have felt, offered to manage a transient institute in a small far away country, after the world glory he had enjoyed.

Towards his sudden death in January 1934, it seemed that Haber came to peace with his Jewish origins and practiced some series self-reflecting, as we can learn from the words he said to Chaim Weizmann after offered the position in Rechovot: “Dr. Weizmann, I was one of the mightiest men in Germany. I was more than a great army commander, more than a captain of industry. I was the founder of industries; my work was essential for the economic and military expansion of Germany. All doors were open to me. But the position which I occupied then, glamorous as it may have seemed, is as nothing compared with yours. You are not creating out of plenty – you are creating out of nothing, in a land which lacks everything; you are trying to restore a derelict people to a sense of dignity. And you are, I think, succeeding. At the end of my life I find myself a bankrupt. When I am gone and forgotten your work will stand, a shining monument, in the long history of our people. Do not ignore the call now; go to Prague, even at the risk that you will suffer grievous disappointment there.”

Haber was born this week, 152 years ago, on December 1868, the first candle of Hanukah, and brought so much light and so much darkens into this world – like no one else ever did.

(Translated from Hebrew by Danna Paz Prins)