The Forgotten Singer: The Exiled Sister of I.J. and Isaac Bashevis Singer, written by Maurice Carr, was recently published by White Goat Press, the imprint of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. Carr has already been dead for 20 years, but only now has this biography come out, in which the author seeks historical justice for his mother, Esther Kreitman.

The forgotten author, who only in recent years has begun to receive recognition as one of the first Jewish feminist writers, was overshadowed by her famous brothers. They did not support her literary career and gave her no financial backing. Some people even claim that Isaac Bashevis Singer refused to help her obtain a visa to the United States. Although he became a literary superstar only after her death, her brother had enough connections and money to come to her aid while she was still alive. After she died, Isaac Bashevis Singer praised her writing just once, but prior to that he shunned her.

On her part, Kreitman never used the name Singer to advance her career. On the contrary – she wrote under the name of Esther Kreitman, with Kreitman being her husband’s last name, whom she married against her will. “Not only did she lack a room of her own, but also a name of her own,” wrote the British Jewish author, Clive Sinclair.

Everyone has heard of Isaac Bashevis Singer who, among other things, was a Nobel Prize laureate. His brother, I.J. (Israel Joshua) Singer, was also a well-known author who was popular with Yiddish readers. But the name Esther Kreitman only a few people are familiar with. Kreitman, whose birth name was Hinde Esther Singer, was two years older than Israel Joshua, and 11 years or 13 years older than Isaac (Bashevis Singer’s year of birth is a subject of debate). Esther was the first of her siblings to write stories. She inspired her brothers to write and also to distance themselves from religion. Both of them were handsomely rewarded for their efforts, but she paid a heavy price for pursuing her ambitions.

Similar to her brothers, Kreitman also wrote in Yiddish. She published short stories in a number of magazines as well as two novels and a collection of stories. Even though the reviews in Yiddish-speaking circles were favorable, she did not achieve great success. When people wrote about her, she was always referred to as “the forgotten sister,” “the scorned sister” or “the ostracized sister.”

Hinde Esther Singer was born into a Chassidic family in Bilgoraj, Poland in 1891. Her parents were Rabbi Pinkhos Mendel Singer and Batsheva Singer (Hinde’s brother Isaac added the name Bashevis to his own name in honor of their mother). Esther was the oldest of four children. The youngest brother, Moses, became a rabbi.

Esther’s parents were disappointed that she was born a girl. They handed her over to an impoverished wet nurse, herself the mother of many children. She confined the baby to a cot placed beneath a table, where Esther almost went blind due to the cobwebs and the dust. She would later describe that terrible episode in her life with sad humor in the short story Di Naye Velt (The New World). Esther’s mother, who came to visit her once a week, never touched or hugged her, and at the age of three she was brought back home. Her eyesight improved, but she remained frail for the rest of her life, both physically and emotionally. Epilepsy and paranoias were among her ailments. Some people called her hysterical or crazy, including her brother Isaac. She herself felt persecuted by demons.

Because her parents refused to provide her with any formal education, Esther taught herself how to read and also learned a number of languages. At the age of 21, her parents married her off to Avraham Kreitman, a diamond cutter from Antwerp, Belgium. On the train journey to her wedding, which was held in Berlin, Esther tore up the notebooks in which she had written some short stories and tossed them out the window. According to an article by Prof. Ari L. Goldman that was published in the New York Times, it was her mother who made her do it. The reason was fear of the Tsar’s border officials, who may have interpreted the Yiddish texts as being seditious. However, that seminal story in Kreitman’s biography has much greater significance. Her mother was also an intellectual whose life circumstances kept her from fulfilling her desire to be educated. She demanded that Esther comply with the norms expected of a Jewish woman. Some believe that she was also jealous of her daughter.

“In Europe some years before World War I, a young woman on her way to marry a man she had never met and would never love shared a secret with her mother as their train rushed through the Polish countryside. She unwrapped a parcel and showed her mother pages and pages of stories, essays and fantasies she had written in secret. ‘Tear them up and throw them out the window,’ the mother commanded. The young woman obeyed.”

Kreitman’s unhappy marriage produced a son: Morris Kreitman, who went by the name Maurice Carr. He was born in Antwerp in 1913 and died in Paris in 2003. He was an author, translator and journalist who worked, among other places, for the BBC, Daily Telegraph, Jerusalem Post, Maariv and Haaretz. When publishing his books, he wrote under the pseudonym Martin Lea. His wife Lola was a painter, as is their daughter, Hazel Carr.

Esther tried to devote herself to family life, but her passion for writing was something she could not control. She left her husband more than once in London – where the Kreitmans had settled – and returned to Warsaw in order to embark on a literary career. But she kept on going back to her husband over and over again. In London, they lived a life of poverty (her father-in-law stopped his supply of money to them as soon as they distanced themselves from Judaism), and they did not have steady jobs. For a while, Esther worked as a seamstress, but most of her income came from writing and translations. In 1930, she began publishing short stories in Yiddish newspapers and literary journals, in addition to translating literary classics from English into Yiddish.

In 1954, Esther Kreitman died in her London apartment at the age of 63. According to her wishes and contrary to Jewish law, she was cremated. She explained that demons had been pursuing her all her life, and she didn’t want them give them an opportunity to continue tormenting her in her grave.

Kreitman’s works were virtually forgotten after her death. In the 1980’s, Yiddish literature researchers began taking a renewed interest in her writing. In 1991, the centennial of her birth, Clive Sinclair wrote an article about her in Lilith, a Jewish-feminist magazine, in which he called her a feminist trailblazer.

In recent years, David Paul, a London-based publishing house whose focus is on books of Jewish interest, released English translations of the three books that Kreitman published in her lifetime. Two of them had already appeared in English, whereas the third was published in English for the first time. The first, which came out in 2004, is a collection of stories set in Poland and in London, entitled Blitz and Other Stories. That collection was originally published in Yiddish in 1950 under the name Yichus (Pedigree). The first half takes place in a shtetl, and the other half in London, where Kreitman experienced the blitz during World War II.

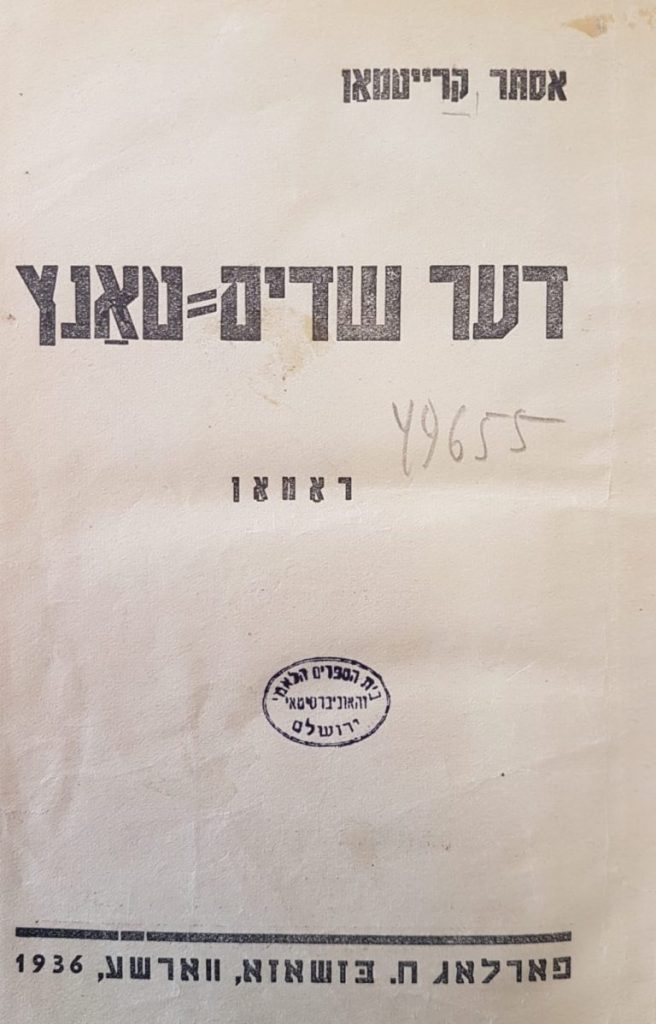

Kreitman’s first novel, which is considered her most important work, came out in English in 2004 as well. The original edition of Der Sheydim Tants (The Dance of the Demons) was published in Yiddish in Warsaw in 1936. Ten years later, it was translated by her son under the more sanitized title of Deborah. It is a semi-autobiographical novel in which Kreitman describes the shtetl and Jewish Warsaw that we know from her brothers’ books, but presented from her unique perspective. As a woman, her childhood and adolescence looked very different than those of her brothers.

Deborah tells the story of a rabbi’s daughter in Poland who rebels against the place of women in the ultra-Orthodox Jewish world. The book’s protagonist is talented, smart and inquisitive, but is plagued by the fact that she is trapped in a world that doesn’t allow her to fulfill herself. Unlike her father and brothers, she is barred from studying Torah. So, she hides books behind the stove in the kitchen and reads them in secret. She falls in love with a communist, but ends up following what is expected of her and agrees to an arranged marriage, which leaves her miserable and desperate. Her only desire is to escape.

If the novel is a depiction of Kreitman’s own life story, her father was a devout Chassid and a follower of mysticism, who was impractical and detached from his surroundings. Although her mother was aloof and educated, she came to terms with her place in the world and did not try to come out against it, even if it made her bitter and frustrated. Deborah/Esther, on the other hand, resists with all her might.

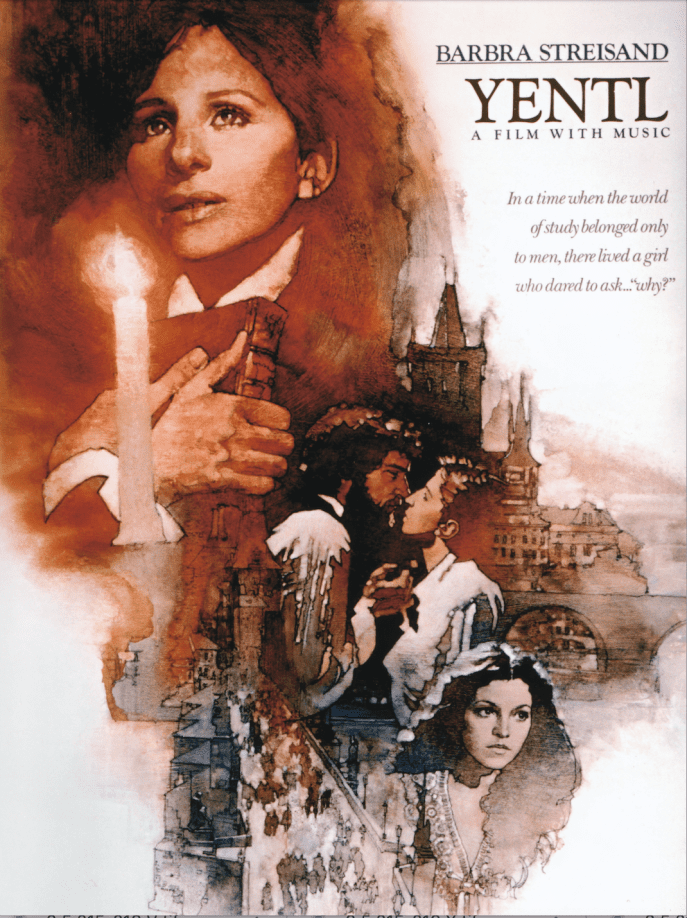

Esther Kreitman provided inspiration for Yentl, the main character in Yentl the Yeshiva Boy, which was written by her younger brother. It tells the story of a girl who disguises herself as a boy so she can study Torah. Yentl is known worldwide thanks to the film starring Barbra Streisand that is based on Bashevis Singer’s story (by the way, he was not a big fan of hers). Like Yentl, Esther Kreitman and her fictional protagonist, Deborah, wanted to be free people – free to study and free to write. But unlike Yentl, who became famous, Esther Kreitman was forgotten.

Kreitman was very skilled at describing the Jewish world of her period in Europe, and she wrote with rage, courage and passion about a woman who fought for her right to fulfill herself. It was a difficult war for any woman of her time to wage, and all the more so for a Jewish woman from an ultra-Orthodox family. In 1983, thirty years after her death, Kreitman finally received a certain degree of recognition as a feminist pioneer. That occurred after the British publisher, Virago, which specializes in books written by women, republished Deborah in English. It was later published in the United States by the Feminist Press, but this time under its original title, The Dance of the Demons. The name that appears on the cover is Esther Singer Kreitman, under which the following words appear: “the true-life inspiration for Yentl.” Her connection with the most famous member of the family did not, of course, hurt the sales numbers. Starting in 2009, the Feminist Press introduced Kreitman to a new generation of students of Women’s and Gender Studies, portraying her as a lost Jewish feminist heroine.

The Dance of the Demons/Deborah and Kreitman’s collection of short stories were over the years translated into additional languages. But until fairly recently, the only ones who could enjoy her second novel were Yiddish readers. The original Yiddish edition of Brilyantn (Diamonds) was published in Poland in 1944. The first ever English translation of that novel was published by David Paul Books in 2010. Brilyantn (Diamonds), which takes place in Antwerp and in London, tells the story of a wealthy, but unscrupulous, Jewish diamond merchant whose world collapses during World War I. Similar to every other theme she wrote about, Kreitman was also closely familiar with the inner workings of the diamond industry in Antwerp.

Kreitman’s books have never been published in Hebrew. To the best of our knowledge, the only work that has been translated into Hebrew is her short story Di Naye Velt (The New World). In 2008, Dr. Leah Garfinkel translated that story and also wrote an article about Kreitman that appeared in the magazine Criticism and Commentary, a publication of Bar-Ilan University. In 2018, a second translation of the story was published by Yehudit Levin in the literary magazine Ho!. And in 2022, yet another translation was published by Dori Parnes (who also wrote a fascinating foreword about the author) on Iberzets, which features Yiddish works that have been translated into Hebrew.

Additional Hebrew translations could possibly exist. Other stories by Kreitman may have been translated and published at some time or another in literary magazines. But none of her books were ever published in Israel for the general public to enjoy. It will please us to learn that others have in fact made the effort. The time has come for historical justice for Esther Kreitman (née Singer), a truly brave female trailblazer.