Many of us spend significant time on trains every day traveling to the office and back. Some devote their train time to working, others to putting out bureaucratic fires, and the rest leaf through the daily papers or take a brief nap. But how many people do you know who exploit their time on the train to contemplate the concept of “time” itself?

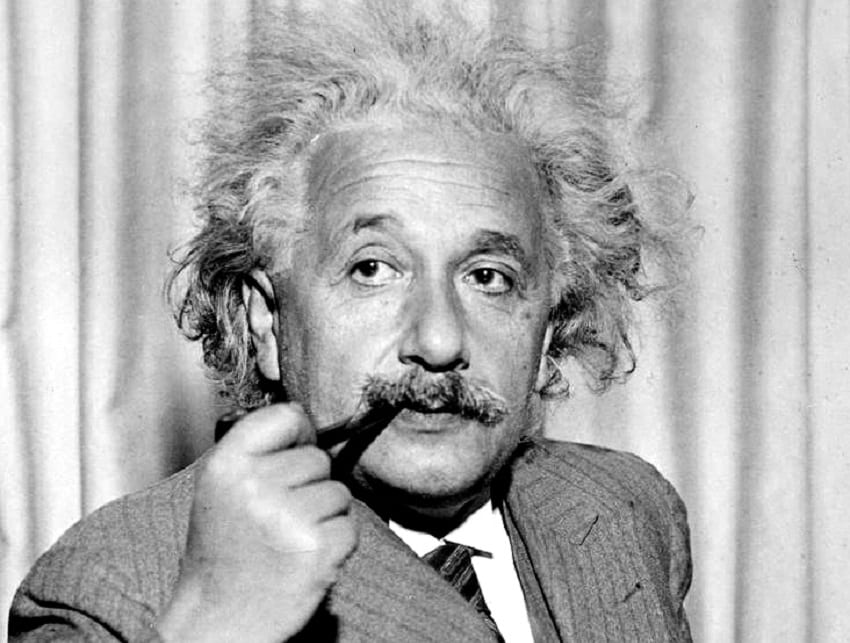

In 1905, Albert Einstein worked in the government patent office in Bern, Switzerland. He traveled to and from the office by train. There, he said, he conducted imaginary experiments in his head, in which he examined how the speed of light influenced the relativity of time between the moving train car and the people standing on the station platform. He turned his “thought-experiments” into four brilliant papers – each of them revolutionary and groundbreaking in its field.

The year 1905 is called the “miracle year” in the history of physics. The four papers that were eventually incorporated in the “General Theory of Relativity” made the man his physics high school teacher called “chronically lazy” into an international icon. His face graced the covers of prestigious magazines and he was treated with honors typically reserved for royalty wherever he went.

The most astounding aspect of this is how he has influenced billions. Whenever you type in a Waze destination, set off a sensor-based alarm, remove a hair with laser, or watch the Prime Minister warn you of the Iranian nuclear threat – know that none of it would have happened, for good or bad, without Einstein. And many other varied aspects of our lives are a result of the bounty embodied in the singular genius’s inventions and discoveries.

The star of our current story also valued Einstein’s great contribution to humanity. But unlike us, he had direct access to Einstein’s brain.

We jump 50 years forward. The date is April 18, 1955. Einstein’s body lies on a hospital bed in Princeton, New Jersey, following his death from an aneurysm of the abdominal aorta. The rumor spreads like wildfire. The genius is dead. Mere minutes pass before scientists, reporters, relatives and friends rush to the scene. Witnesses describe the atmosphere as the earthshaking loss of a founding father. One of them said, “We felt that the laws of physics he discovered would collapse with his body.”

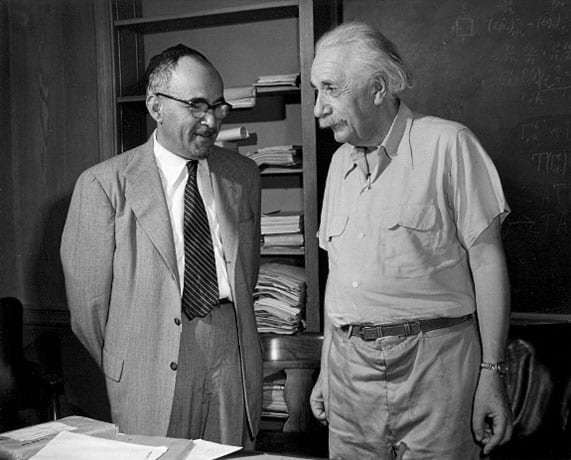

Several kilometers away and at the same time, a young man named Thomas Harvey took leave of his wife and children to go to work at the hospital. Before he left home, his wife put a jar of granola cookies for his 10 am coffee break into her husband’s bag. When Harvey approached the hospital entranced, he discovered a crowd gathering outside. He instantly comprehended that something astonishing had happened. When he arrived at the entrance, he was alerted to rush to the operating room. Thomas Harvey was the chief pathologist of Princeton Hospital.

The ever-curious Harvey understood that he had been granted a rare opportunity. He was to perform the autopsy on the smartest man in the world, who was also his personal hero. American law in those days had yet to define clear protocol for autopsies. Harvey knew that hadn’t much time, because Einstein had clarified in his will that “I want to be cremated so people won’t come to worship at my bones.”

While he was still operating on Einstein, Harvey secretly came to a decision. Several hours later, he exploited the cover of the crowd to surreptitiously leave the hospital with his wife’s cookie jar in hand. But something other than cookies filled the jar: slimy liquid with whitish flakes floating on top.

Harvey kept Einstein’s brain in the granola cookie jar for 40 years, guarding the genius’s brain with his life. Neither loss of livelihood nor exile from the scientific community caused the pathologist to give up the stolen goods. Harvey used a 35mm camera to take dozens of black-and-white shots of the excised brain, before slicing it 240 times. The man was obsessed with studying his hero’s brain.

When he gave up on solving the great mystery himself, he decided to send it to scientists in hope that they could uncover the secret of Einstein’s genius. A scientist named Marian Diamond received a mailed package from Harvey. The certified pathologist decided to take a different tack this time: He mailed the sampled brain tissue in a mayonnaise jar. When Diamond examined Einstein’s sampled brain, she found something interesting. Behind the area of the brain responsible for complex thought and creativity, there was a large number of the specialized cells responsible for holding the brain tissue together called astrocytes – the brain’s superglue, if you will.

Years later, another researcher found that astrocytes have a fascinating quality. They can communicate among themselves by means of chemical signals, creating in effect what scientists call “a brain within the brain.” That might have explained why Einstein conceived things that average people did not. They lacked what he had – “another brain.”

In 1995, about 40 years after Einstein’s death, an American writer, Michael Paterniti, was looking for material for his new book. When it occurred to him to write about the peculiar incident in which a man stole the most creative brain in human history, he contacted Harvey on the phone. In the course of conversation, Harvey mentioned his desire to travel to California to return the brain to Einstein’s granddaughter. Paterniti heard himself saying, “I’ll drive you.” For 11 days, the man in his early 30s and the 80+ doctor shared the car, with what was left of Einstein’s brain in the trunk.

“He brought out his bags,” Paterniti says, “and in one bag he had a Tupperware container in which he had stashed the brain.” Paterniti describes the bizarre journey – in which the pair also visited the home of the heroin-addicted poet William S. Burroughs – in a wonderful book entitled, “Driving Mr. Albert: A Trip Across America with Einstein’s Brain.” The book ends with them knocking on the door of the granddaughter, who refuses to receive the brain.

Harvey died in 2007. In his will, he donated the remaining brain samples to the local hospital in Princeton – the same hospital from which he stole Einstein’s brain.