Hereby is an alternative narrative of the biblical story of the Exodus, based on historical and archaeological findings, as well as Egyptian anti Jewish literature regarding the origin of the Jewish nation and the character of Moses. This alternative story relies on Prof. Israel Knohl’s fascinating book How the Bible Was Born.

The first author to offer us a glimpse on the Egyptian Exodus story is the Egyptian Greek historian Manetho, who lived in Alexandria in the Ptolemaic period in the 3rd century B.C.

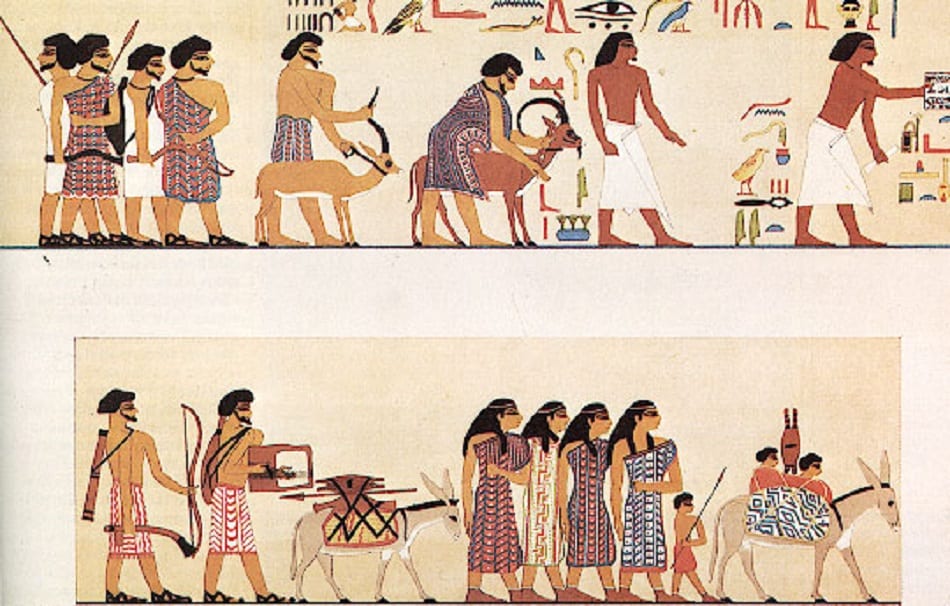

Manetho reports that in the 17th century B.C., foreign invaders called the shepherds – Hyksos in Egyptian – came to Egypt and took hold of the throne. They burnt down Egyptian cities, destroyed idols, and shattered temples, performing “horrible hate crimes against all the country’s natives”. Then after a while the Hyksos were expelled from Egypt by one Pharaoh. At this stage of the text, Manetho reveals their real identity: “They left the land of Egypt with their families and possessions, and went through the desert to Syria however, fearing the Assyrian rulers, they established a city for themselves in the land then called Judea.”

Manetho’s text, which determines that the shepherds were the ancestors of the Jews, goes on and conveys yet another story. Centuries after the Hyksos were expelled from Egypt, the Egyptian ruler, Pharaoh Amenhotep, wished to seek the advice of the gods. His consultants told him the only way to approach the gods was to cleanse Egypt from the lepers that were living by the border. Amenhotep gathered all the lepers under his territory, and concentrated them in the abandoned city of Avaris, formerly capital of the Hyksos. The lepers upraised and rebelled against him, led by a leper priest called Osarseph, who founded for them a new, hostile religion, of which the main principles were denial of polytheism and the faith in a single god. According to some researchers, Osarseph drew his monotheistic ideas from Pharaoh Akhenaten, who ruled over Egypt in prior centuries.

Manetho reports that Osarseph sent messengers abroad in order to establish a military aid force, requesting also the help of the descendants of the Hyksos, the Judean shepherds, who came in masses to support him and the lepers. Together they formed a strong new force that took over Egypt. The new ruler Osarseph, leader of the lepers, then became king, who collected taxes, and preached against the Egyptian gods. So who was Osarseph? According to Manetho, after joining the Hyksos, Osarseph changed his name to Moses. Though he does refer to Moses as a fanatic hater and isolationist, Manetho also talks of Moses’ unique wisdom, courage, and what the Egyptians called a divine presence, a description that complies with Moses’ biblical description in Exodus, 11, 3: “the man Moses was very great in the land of Egypt, in the sight of Pharaoh’s servants, and in the sight of the people.”

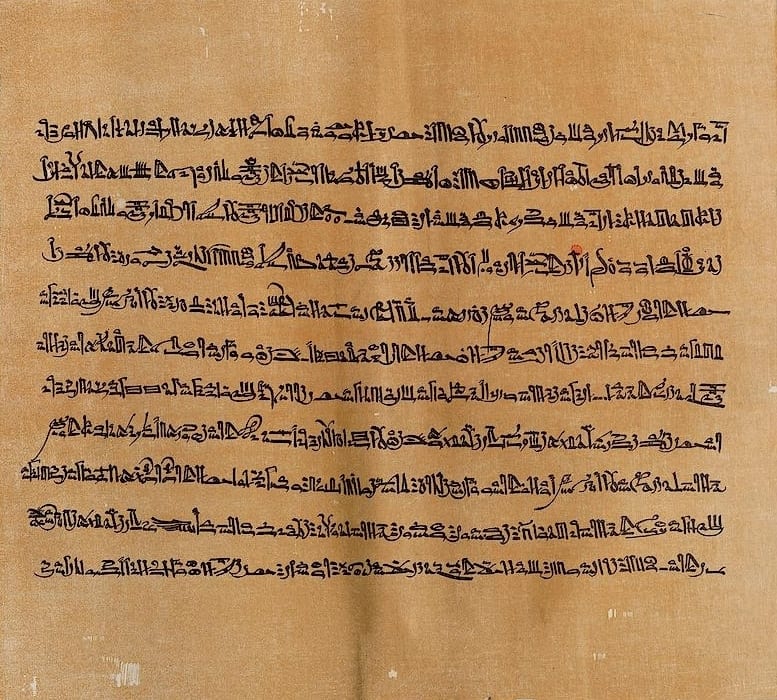

Let us now discuss the Great Harris Papyrus – the longest known papyrus from Egypt (40 meters long), discovered in a grave near the state of Habu across from Luxor, on the west bank of the Nile. The Harris Papyrus speaks of a time in which Egypt was a deserted land, lacking solid leadership, until a man by the name of Irsu came to power. The literal meaning of his name is pretender, a man from outside the dynasty, who pretends to be king. Irsu was also a Kharru , that is, originated from either Canaan or across the Jordan river, territories called in Kharru Egyptian. These two titles imply that Irsu was not worthy of the throne. Reading onwards we learn that Irsu collected taxed, used to put down the Egyptian religion and prevented the worshipers from bringing their sacrifices to their temples. Then a turning point occurred: when the gods restored their mercy upon Egypt, they placed their son on the throne – Setnakhte, the founding Pharaoh of the 20th dynasty. Setnakhte fought the foreigner, got rid of him, and took the throne.

Another interesting finding, that supports the Harris Papyrus, is a tombstone discovered in Elephantine, dated back to the second year of ruling of Sethnakhte. It tells of Setnakhte, who rehabilitated Egypt after the era of the foreign ruler who broke the religious principles of the pharaohs.

According to the theory of Prof. Knohl, Irsu mentioned in the above sources, the one who despised the Egyptian religion and brought mercenaries from Canaan, was in fact our Moses. He supports his assumption by the fact that the queen who ruled before Setnakhte was Twosret, wife of the second Sethi who died in 1196 BC. The documents stated that her rule only lasted two or three years, after which a mysterious enigmatic event took place. An inner struggle broke in Egypt, that ended the 19th dynasty and brought to power a new one, founded by Setnakhte . This brings Knohl to conclude that the struggle was in fact the taking over by Moses and the lepers, joined by the shepherds on the Delta area.

Prof. Knohl dates the Exodus to the second year of the kingship of Pharaoh Setnakhte, around 1186 BC. He explains that Moses’ parents belonged to the descendants of Jacob, who came to Egypt during the famine. Moses grew up in the court under the protection of queen Twosret, who had no children of her own, and is possible the biblical Pharaoh’s daughter who adopted and raised Moses. After her death, Moses saw himself worthy for kingship and used the support of his people, the children of Jacob, who were enslaved in Egypy, for his conquest moves. He then brought additional backup from abroad – the shepherds from Canaan. In the struggle between the two forces, Moses and his men lost, deported from Egypt and went towards Canaan.

This is the Egyptian version then. The rest is history as the cliché goes, or rather – an alternative history. It’s up to you to choose. Happy Pesach!