According to people who lived under the Nazi occupation of Paris, Béatrice de Camondo would often ride her well-groomed horse in the Bois de Boulogne park, accompanied by a German officer. One can only assume that while meandering among the chestnut and sycamore trees, Béatrice probably entertained the thought that a day would come when her privileged last name would no longer impress the Germans and they would stop providing her with a regular escort. However, even if she let her imagination run wild, it is highly unlikely that she envisioned her life ending soon in the gas chambers of Auschwitz, together with her daughters and husband.

Throughout her life, Béatrice de Camondo assimilated the message that her Judaism was merely a footnote in her glamorous cosmopolitan identity. Her father, the aristocrat Moise de Camondo, taught her that persecutions against Jews were the lot of Yiddish-speaking commoners who behaved as if they were still in ghettos. Even the Dreyfus Affair, which took place when he was a young man, did not undermine the confidence that Moise de Camondo had in his French roots. His habits, his clothing, his cultural preferences and choice of friends all illustrated his unwavering belief that he was part of the glorious Gallic history and not a descendant-slave of the Kingdom of Judah exiles.

If you like, proof of that can be found in his luxurious mansion in Paris, which later become the Nissim de Camondo Museum. Among all the exquisite works of art that decorate the mansion, only a discerning eye will notice two items which suggest that a Jewish family once lived there: the separate sinks in the main kitchen and an elegant set of Rosh Hashanah prayer books, which are well concealed between the thousands of classical works that represent the best of Enlightenment literature.

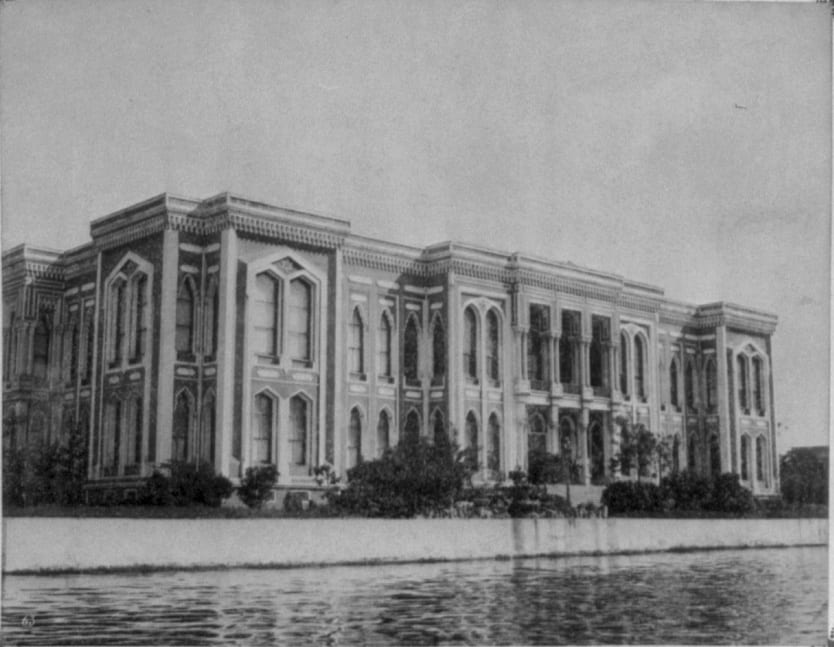

In his epic novel Le dernier des Camondo (The Last of the Camondo Family), Pierre Assouline lays out the amazing story of the Camondo family, who after the expulsion from Spain settled in several different Mediterranean countries. And like other aristocratic families, such as the Ephrussi family and the Rothschild family, the Camondos also established an extensive network of banks in Europe’s major capital cities. In the 19th century, the bank owned by the Camondos financed much of the trade in the Ottoman Empire and its founder, Abraham de Camondo, was even given the title of Count. Based on the value of the currency back then, at the time of Abraham’s death, his estimated wealth amounted to 125 million francs.

In 1863, the Camondo family embarked on the French chapter in their history after settling in Paris, to which they also transferred the bulk of their banking business. Assouline’s novel focuses on Moise de Camondo, a grandson of the founder of the family empire. The death of his daughter and granddaughters in Auschwitz brought an end to the distinguished Camondo family dynasty.

Unlike the previous generations of the family, Moise de Camondo did not have a knack for business. Rather, he was drawn to art, or to be more exact, to collecting works of art. If there is truth in the theory which says that art collectors share the need to compensate for a loss, then Moise de Camondo was definitely proof of that theory. In 1902, his wife Irene left him for the stable manager at their estate. She was the daughter of the Jewish financier Louis Cahen d’Anvers, who headed a bank that would later become a global financial institution – BNP Paribas. Irene disappeared from his life forever, leaving him heartbroken and alone with their two children – Béatrice and Nissim.

Moise de Camondo chose to sweeten the bitter pill by renovating the family mansion located on 63 de Monceau Street in the upscale 17th arrondissement (district) of Paris. As noted by the author Edmund de Wall, it hosted an unprecedented blend of financial aristocracy, Jewish aristocracy, well-known artists and writers, and upper class bourgeoise. The latter included the renowned playwright Edmond Rostand (who wrote Cyrano de Bergerac), the celebrated author Marcel Pagnol (who wrote Jean de Florette), and the famous courtesan Genevieve Lantelme, whose involvement in a romantic triangle inspired Marcel Proust to write In Search of Lost Time. And the acclaimed Jewish actress, Sarah Bernhardt, lived a few doors away – to mention just a few.

Moise de Camondo, who was 9 years old when he first came to Paris, was enamored of the city of his youth and of French culture. As an avid Francophile, his main interest was in collecting works of art from the 18th century that been created shortly before the start of the French Revolution – “the great century of the Enlightenment” – which was an age when “France was really France.” To fulfill his fantasy, Moise hired the noted architect, René Sergent, who was commissioned to design a mansion in the style of the Petit Trianon, the palace located in the gardens of Versailles that was home to Madame de Pompadour, a mistress of Louis XV.

Moise de Camondo’s obsession with 18th century neoclassical art did not end with the architectural design of his mansion. That was just the start of it. The Jewish collector devoted all his time and energy to acquiring works of decorative art from the 18th century, including a furniture set designed by the iconic furniture maker Georges Jacob, a desk created by the cabinetmaker Jean-Francois Oeben, who was Madame de Pompadour’s carpenter of choice, rare glass objects from China that were popular in the reign of Louis XVI, and silver dinnerware designed by the silversmith Jacques Nicolas Roettiers, commissioned by the Russian Empress Catherine the Great for her lover, Grigory Orlov. All these artifacts were just a small part of the splendid artistic repertoire housed in the mansion.

On September 5, 1917, Moise de Camondo suffered another loss when his son Nissim, a combat pilot serving in the French Air Force, was shot down during World War I. Following this great tragedy, Moise sunk into a depression and seldom left home. At the same time, his obsession with collecting objects only intensified. In an attempt to cling to what was familiar, he continued to collect a growing number of works of decorative art, including a rare porcelain service that was manufactured at a factory in the city of Meissen, which is considered Europe’s first porcelain factory.

Moise de Camondo died in 1935. In his will, he wrote that his lifelong project had focused on glorifying French culture “in the period I loved more than any other.” He appointed his daughter Béatrice to be the guardian over the rare artifacts and left her strict instructions. She was not allowed to loan out any works of art or add or acquire new ones. He even forbade her from moving any pieces of furniture or paintings from one place to another unless they remained in the same room.

On January 4, 1945, Béatrice, her husband and their two daughters were murdered in Auschwitz. Because the Camondo family had no other offspring, the mansion was transferred to the French government, which converted it into a museum named after Moise’s son, Nissim. Since then, the home and all its furnishings have remained exactly the same, as if frozen in time.

The story of the Camondo family is on display at ANU – Museum of the Jewish People that was recently dedicated in Tel Aviv.