Historical research indicates that there were Jews in ancient Ethiopia, but their unknown origin and history has inspired many varying theories. The debate among researchers focuses mainly on the quality of the ethnic affiliation between those ancient Jews and the Jews who were first documented in the 9th-Century writings of Eldad HaDani and in Ethiopian sources in the 14th-Century.

The Jewish community in Ethiopia, Beta Israel, cites various traditions as to their origins. One tradition maintains that Jews arrived in Ethiopia in waves, mainly via the Nile and its tributaries. Other traditions associate the Jews’ arrival in Ethiopia with the story in the Ethiopian national opus “Kebra Nagast” of the procession of Menelik I, the son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

The origins of the early Jews cited in Jewish sources – Eldad HaDani in the 9th Century, Benjamin of Tudela in the 12th Century and Elijah of Ferrara in the 15th Century – are few and they lack a historical basis. More specific reports appear in the Ethiopian Chronicles (Divrei Hayamim), maintaining that Judaism was common in the Aksum Kingdom established in the 2nd Century by Semite immigrants from Southern Arabia. The kingdom under the influence of Byzantine Rome adopted Christianity in the 4th Century. The subsequent persecution of Jews caused them to flee to the mountainous inland regions north of Lake Tana.

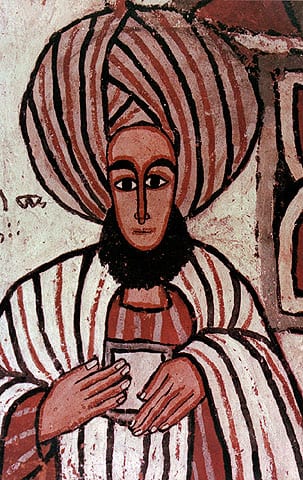

The group of Jews who came to be called “falasha” – Ge’ez for “exiles” or “immigrants” – coalesced and gained strength until they established an independent Jewish kingdom. The Jewish kingdom took part with the rebels in the 10th-Century rebellion against the Aksum rulers and the Christian church. The community’s tradition has it that a Queen of Jewish origin named Yehudit (Judith) led the rebels. The story – relying half on legend and half on history – says that Yehudit repelled the invaders and established a Jewish government that lasted 40 years.

The Solomonic Dynasty took power in the 12th Century, and established itself by means of conquests and promoting Christianity in pagan, Muslim and Jewish regions. Christian missionary activity in the 14th Century focused on the Jews of Shewa. Churches and monasteries were built in their midst. During that period, Ethiopians invaded Jewish regions and conquered what remained of Begamdar, the districts of Wagra and Dembia. The Ethiopian army established military outposts in Seklat and Gondar to fortify its occupation. That gave rise to a Jewish rebellion that was harshly put down, and missionary activity in the region escalated.

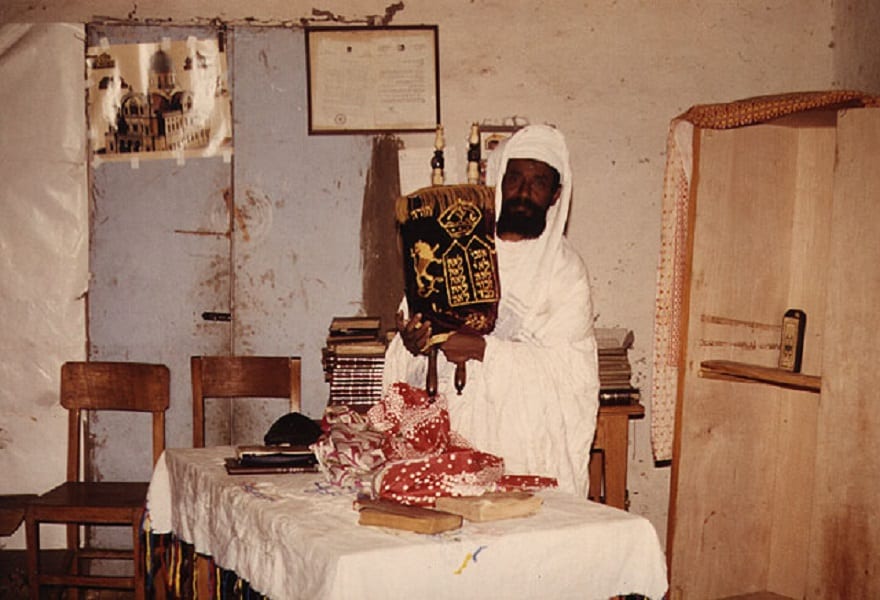

Ethiopian Jews were hurt physically and economically in this battle. Emperor Amda Seyon (1314-1344) waged a war to the death against the Jews and the Muslims. His great-grandson, Emperor Ishak (1414-1429), followed in his footsteps with sharpened focus. He singled out the Jews, threatening that if they did not convert to Christianity, they would lose their land rights. When they failed to surrender, their lands were seized and they were labeled “falasha.” During the years 1434-1468, Emperor Zera Yakob’s continued persecution of the Jews earned him the title of “Destroyer of the Jews.” The Ethiopian Jews continued to fight and even managed to bolster Judaism’s influence. Jews sacrificed their lives during that period to preserve their Judaism, and a monastic status unique to Ethiopian Jewry developed. Those monks played a key role in preserving tradition and fighting attempts to force Christianity on the Jewish community. They copied the Orit (Torah) texts and distributed them to the community.

Similar battles took place in the region until the 15th Century. And in the late 16th Century, the Ethiopians began to move their wandering capital to a region in North Ethiopia where most of the Jewish community lived. The relocation of the capital entailed progressive “Amharicization” (increased adoption of Amharic as the official language among non-Amharic-speaking ethnic groups) and conversion to Christianity among Jews and local pagans. The movement of the center of the Ethiopian kingdom to the center of the Jews independent region caused them to feel threatened and initiate a number of military responses. These battles – some of them successful – were viciously crushed and provoked the movement of the Ethiopian capital to the heart of the Jewish settlement. The last Jewish battle took place in the early 17th Century, when a mountain ridge on which the Jews lived was conquered.

In 1552, Rabbi David ben Zimra (the Radbaz), then-leader of Egyptian Jewry, determined that in accordance with Halacha, the Beta Israel were Jews and members of the Jewish People like all others. In 1632, 80 years later, what Ethiopian history calls the “Revival” began. That period was characterized by Ethiopian Emperor Fasilides’ orders to expel the Portuguese armies, and his restoration of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Known for his tolerance, the Emperor nonetheless completed the Ethiopian Inquisition that his father had begun in 1624. Fasilides banished Jesuit soldiers and missionaries from the land of Ethiopia and forbade Europeans from entering his empire. Under his influence, the Ethiopian Empire flourished politically, culturally, and creatively, paralleling the European Renaissance. The religious tolerance typical to that period benefitted the Beta Israel community. Its artists and sages joined the elite that led the empire.

Hebrew began to disappear as a ritual language in the mid-16th Century and vanished completely by the early 17th Century. Ge’ez then became the accepted language of Jewish ritual. From the early 17th Century to the last half of the 19th Century, the community spoke both the Amharic and Tigrinya languages. The script used in all the aforementioned Ethiopian languages is the Habesha Script.

In 1862, a monk named Abba Mehari led thousands of Jews to Ethiopia via the Red Sea. They believed that God would perform a miracle on their behalf like that of the parting of the Red Sea on the journey out of Egypt. This ended in tragedy. Many of them died of starvation and epidemic disease before crossing the Ethiopian border. The failed attempt to make aliya to Jerusalem heightened the belief that there was no way to go to the Holy Land, and prompted a certain sense of despair.

In 1864, two years later, Rabbi Azriel Hildesheimer, a major rabbi in Germany, published a call to action in which he unequivocally recognized the Judaism of Beta Israel and determined that the obligation to save and assist them comprised Arvut Israel – Jews’ mutual responsibility.

The missionary Samuel Gobat arrived in Ethiopia in the early 19th Century. Gobat met with and wrote about the Beta Israel community, and after that meeting, organized a mission to the Beta Israel community. The mission began to operate in 1860 under the management of the Church’s general mission to the Jews. The Beta Israel community’s resistance to the missionaries led to their expulsion from their villages and religious debate surrounding their customs – including their offering of sacrifices.

In 1867, the famous French-Jewish Middle-East historian and traveler Joseph Halevy arrived in the Beta Israel community. He was sent by Diaspora rabbis to examine how the community’s Jews were faring under the Christian mission. A period in the second half of the 19th Century came to be known by Ethiopians as “the Bad Times” – seven straight years of drought, wars, and epidemics in which two-thirds of the Jews died.

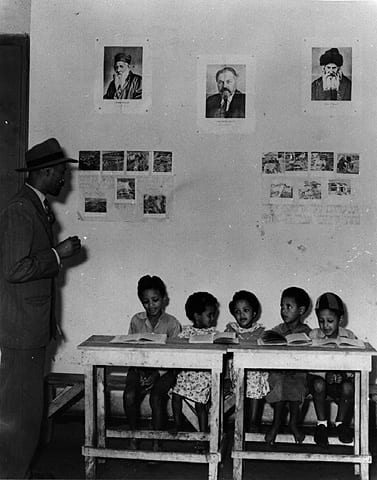

In the early 20th Century, Joseph Halevy’s student, Jacques (Yaakov) Faitlovitch arrived in Ethiopia. His arrival began a continuous connection between the rest of Diaspora Jewry and the Jewish community in Ethiopia. The missionary activity continued in parallel. From 1922, Faitlovitch sent youth “from Beta Israel” to Jewish educational institutions in Europe and the Land of Israel in order to make them leaders and emissaries to their community. In 1946, Dr. Faitlovitch spearheaded the establishment of the first Ethiopian-Jewish boarding school, in the village of Uzebba in Gondar. The village serving children of the Beta Israel community from all the nearby villages was run by leader and educator Yona Bogala.

During the Italian occupation (1936-1941) their connection with the rest of world Jewry was severed. The local government’s relations with the Jews were adversarial and many of them joined the Patriot movement. The race laws published in Italy in 1938 did not help the Jews, and many of them were executed because of the rebellion. In 1941, orders were issued to implement the plan to exterminate Beta Israel, in conjunction with the collaboration with Nazi Germany. But the Italians’ defeat by Allied Forces in the Ethiopian War of Independence prevented the plan’s realization. Emperor Haile Selassie returned to government and adopted a policy of Amharicization of Ethiopian peoples. In 1948 and in line with that, he approved the Christian mission’s continued activities in the Jewish community.

In 1973, then-interior minister Yosef Burg issued deportation orders to members of the Ethiopian community in Israel, claiming that the Law of Return did not apply to them. These Jews hid in places provided by the Public Committee for Ethiopian Jewry. The committee members appealed to the Rishon LeZion Rabbi Ovadya Yosef to thwart the deportations. Most 20th Century poskim (legal religious scholars) addressed the Ethiopians’ Judaism with skepticism. But Rabbi Ovadya Yosef relied on the Rambam’s 15th-Century claim that they were members of the Dan Tribe, who had been exiled during the First-Temple-Period destruction of the Kingdom of Israel by the Assyrians. Rabbi Ovadya’s ruling was dispatched to a special government committee charged with examining the Ethiopian issue in 1974. That paved the way for the Ethiopian Aliya. In contrast with the Chief Rabbis who succeeded Rav Ovadya and demanded that the Ethiopian olim must undergo ritual immersion to satisfy the laws of conversion – and in contrast with all the ultra-Orthodox rabbis – Rabbi Ovadya insisted that the Ethiopians were Jews in every sense and not required to undergo any process of conversion.

(Translated by Varda Spiegel)