After a choppy and bizarre season, as the whole sports was hit by the pandemic, then a well-organized bubble in Orlando, the NBA has reached its annual pinnacle. And at a time of year when players are usually preparing for the new season, the finals series has begun featuring the Los Angeles Lakers and Miami Heat.

Typically to our era the Jewish involvement in the finals is at the higher ranks. Like the owner of the heat Micky Arison and league commissioner Adam Silver, who will award the trophy to the winning team. The last time a Jewish player featured in the finals was when Jordan Farmer was part of the winning Lakers team in 2010. In the 21st century David Blatt was the losing coach with the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2015 and Larry Brown, one of the greatest NBA coaches of all time, led the Detroit Pistons to the title in 2004.

But things were very different in 1947, when the Philadelphia Warriors and Chicago Stags met in the first finals of the league, that then called itself the BAA.

The Warriors, who won the series 4-1, went on to become one of the world’s most famous clubs. Currently known as Golden State, led by Steph Curry and calling the Bay Area home. The Stags, however, ceased to exist within five years of operation.

A glimpse into this future can be seen in one statistic of this inaugural series. Only 2,000 spectators bothered to attend the two games in Chicago, a city that was historically indifferent to pro basketball until the arrival of fellow named Michael Jordan almost four decades later. In Philadelphia, on the other hand, 8,000 spectators packed the old Philadelphia Arena in a city that had taken the game to it’s heart. And the person most responsible for this basketball craze was Eddie “The Mogul” Gottlieb – perhaps the most influential person in early professional basketball.

The Gottlieb’s obituary in the New York Times in 1979 mistakenly states that he was born in New York, but in fact he was born as Isidore Gottlieb in 1898 in Kiev. He came to the United States aged four, part of the wave of Jewish immigrants arriving at Ellis Island with dreams of a better future. Eddie’s early days in America were difficult. His father died when he was nine and the relocated to South Philadelphia. As a child he received 15 cents a day for school for travel and lunch. On nice days he would walk and save the money.

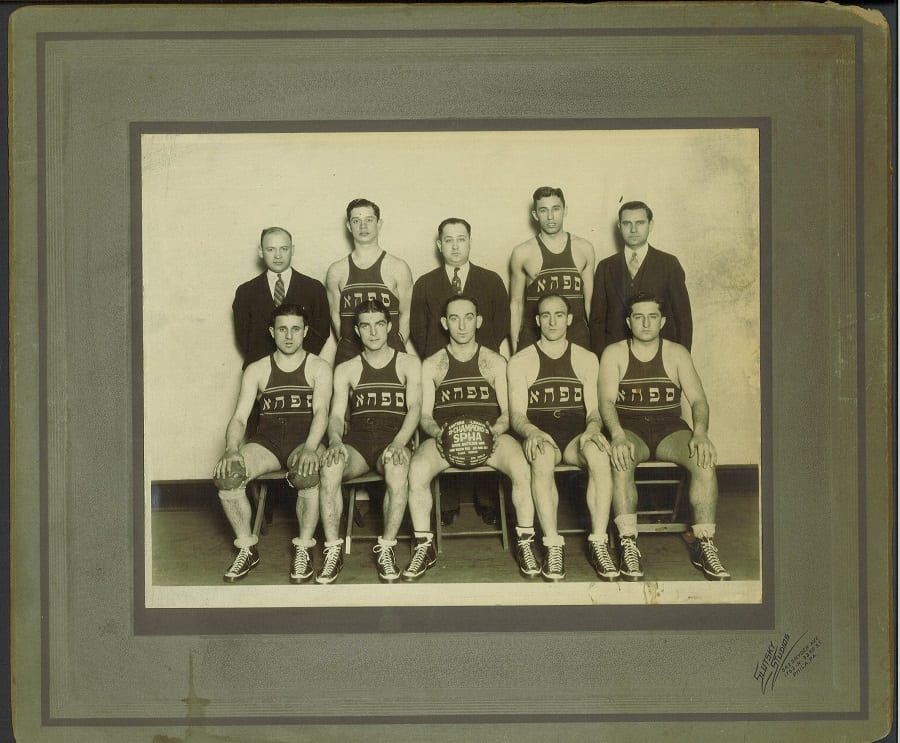

In middle school he began basketball – a young sport invented less than twenty years earlier. He loved the game an upon graduating from high school – he formed a basketball team, with the modest aim to keep his high school team together. The team, soon to be named the Philadelphia SPHAS – an acronym for “South Philadelphia Hebrew Association” – developed and grew and by the early 1930s was playing in front of thousands in the huge ballroom of the Broadwood Hotel. Carrying the ספהא Hebrew letters with pride on their playing Jerseys.

How did Gottlieb draw large crowd to watch a Jewish team play hoops? With a very early understanding of basketball and sports as entertainment for the entire family and both genders – and in the case of the SPHAS a savvy understanding of the target audience.

Admission to SPHAS games was 65 cents for men and 35 cents for women. But it wasn’t the reduced price that created basketball interest amongst young Jewish women but what happened later. Once the game ended an orchestra took the stage and the evening continued with a dance.

Jewish families of the time often forbade their daughters from visiting Philadelphia’s dancing halls. The usual reasons of immigrant family values confronting general society. But SPHAS games were a different – as the audience was young Jewish boys of the appropriate age, families actually encouraged their daughters to go to games, so SPHAS games became somewhat of a friendly “meat market” for Philadelphia’s Jewish community. The players incidentally earned relatively good money for the 1920s and 1930s, 30 to 50 dollars a game in an 80 game season.

The SPHAS were also pretty good. They won 12 championships in various leagues, including seven in the ABL-considered the strongest East Coast competition in the pre-NBA era. The Jewish players were so good that one of the most prominent sports journalists of the period, Paul Gallico, even tried to suggest a “scientific” explanation to this phenomena: “the reason, I suspect, that [basketball] appeals to the Hebrew with his Oriental background is that the game places a premium on an alert, scheming mind and flashy trickiness, artful dodging, and general smart-aleckness…”

Indeed, dozens of Jewish basketball star starred in the early years of basketball. Names like Berney Sedran Seder and Lou Sugarman were among the big stars of early 20th century un-organized pro game. Later came players like Lulu Bender and the great Nate Holman. Holman a member of the Basketball Hall of Fame was not only the star of the “Original Celtics”, a famous New York team (with no connection to the current Boston Celtics), but wrote books about the game and became a renowned coach. The Wingate Institute School of Coaching, Israel’s top sports academic institution, is named after him. When basketball was first included in the Olympic Games in 1936, in Nazi Berlin, Sam Balter won gold for the United States and Irving Meretsky won silver with Canada.

Jewish excellence in basketball at the time had its reasons – but they were economic rather than so-called genetic. The size of a basketball court is less than 5,000 square feet, while the size of a baseball field, America’s “National Pastime” is typically 10 times larger. So basketball courts were common in the Jewish ghettos of Philadelphia, New York and Chicago, often built on roofs and caged with fences. Brooklyn native Red Auerbach, later the illustrious patriarchal Boston Celtics coach, leaned his game is such cages.

Baseball would suit Jews of later generations who were economically established and living in the suburbs. Currently there are 14 professional Jewish baseball players in the major leagues, several of them enjoying star status, while we are currently devoid of an active Jewish NBA player.

In 1946, owners of the NHL ice hockey teams, at the advice of league president Maurice Podoloff, decided to make better use of their arenas and establish a national basketball league to maximize revenues. Podoloff was a Jewish lawyer born in the Russian Empire, present-day Ukraine. His family was relatively wealthy, settled in Connecticut and he was a graduate of Yale University. He is the only person to serve as president of two professional leagues simultaneously and his important contribution to the NBA was ruthlessly eradicating corruption and expelling players who have fixed games for life.

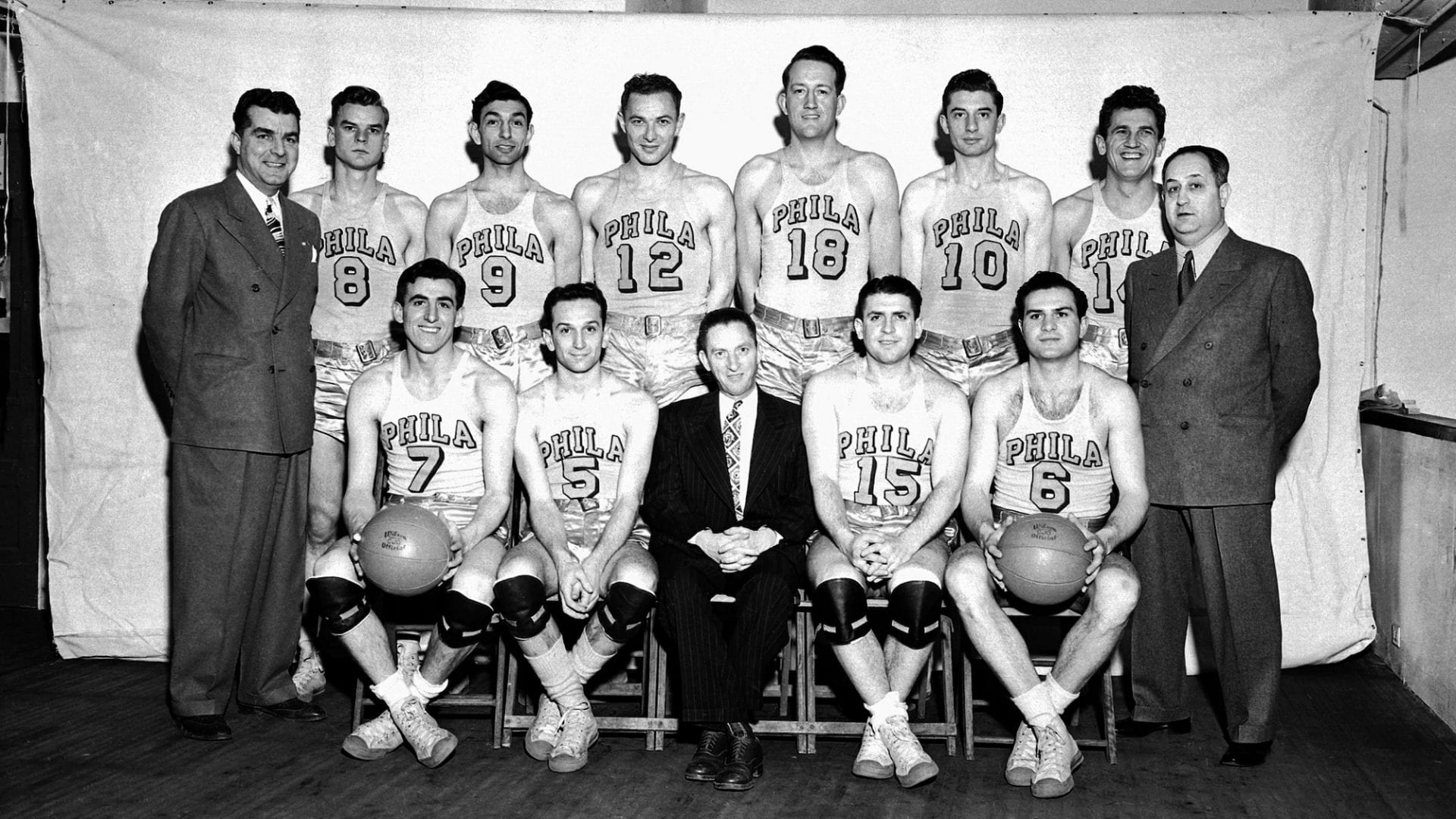

Back to Gottlieb he was now among the founders of the Philadelphia Warriors as head coach and immediately signed most of the SPHAS stars. They included Jerry Fleishman, Petey Rosenberg, George Seneky and Art Hillhouse. Only the first two were Jews as during WWII, with so many young Jewish men volunteering for service, the SPHAS began to recruit non-Jews to their roster. By the time of the final series, Gottlieb will sign another Jewish player, Ralph Kaplowitz.

When the first NBA game began, between the Toronto Huskies and the New York Knicks on November 1, 1946, six Jewish players were on the court. and Ossie Schectman scored the first basket ever in the NBA. Four of the six, Shechtman, Kaplowitz, Sonny Hertzberg and Leo Gottlieb – were New York players. But if one would expect enthusiasm for this phenomena in the world’s largest Jewish city, the reality was disappointing. The old Madison Square Garden was often occupied by a large Irish crowd with anti-Semitic tendencies, often booing the local team for being “too Jewish” for their liking. Management decided to cater to these fans and within a year all four Jewish players would leave the Knicks. Kaplowitz would find his place in Philadelphia, as mentioned, where the audience was largely Jewish and the team enjoyed another great asset. Gottlieb signed Joe Fulks – a dazzling intimidating gentile – to lead his group of ex-SPHAS.

Fulks was the league’s first superstar. He led all scorers averaging 23 points. Gottlieb had signed him for a handsome salary of $8000 a year. The credit of recruiting him goes partly to Petey Rosenberg. He had served with the Kentucky-born Fulks in Pearl Harbor and told Gottlieb he just has to sign him.

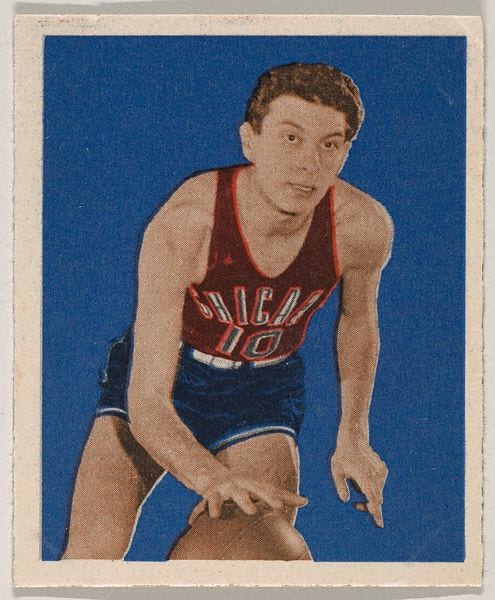

Meantime in Chicago, Philadelphia’s rival, the leading star was Jewish. Brooklyn-born Max Zaslofsky, a was a deadly sniper who was selected to the all-league team in each of his four seasons in Chicago. When Chicago folded at the end of it’s fourth season, Zaslofsky was in such demand that the league held a lottery for his services. The Knicks, who were now happy again to have Jewish players, were the winners and awarded Zaslofsky a $15,000 a year contract. The second Jewish player for Chicago was team captain Mickey Rottner. Extremely popular he grew up in a poor family as one of nine children and thanks to basketball he received a college scholarship to De Paul. Upon graduation he enlisted in the U.S. Army and served for four years during World War II.

The Warriors won the first game in Philadelphia 84-71 starring Fulks who scored 37 points, including 21 in the final quarter – monstrous numbers even in modern standards. In the second game, the Chicago team contained Fulks, so this was the moment for the old SPHAS to take control and lead their city to a second victory in the series. Fleishman scored 16 and Kaplowitz added 14 in an 85-74 victory.

Philadelphia practically secured the series and the title in the next game in Chicago with a 75-72 victory. To this day a 0-3 deficit in an NBA series has never been Fulks led the team with 26 points as Kaplowitz and Fleishman scored 11 each. Chicago seemed broken and with Philadelphia leading 65-52 in the fourth game, again in Chicago, was facing humiliation. But Zaslowski responded brilliantly avoiding the loss of the series on home court. He scored 20 points and Chicago survived with a one-point victory, 74-73.

The series returned to Philadelphia. Chicago was encouraged, fighting to the end but surrendering 83-80 in the final game. The Warriors were crowned Champions and awarded $14,000. Gottlieb, a generous man throughout his life, would give each player a $2,000 bonus.

Gottlieb would not go on to a standout coaching career. His historical role was destined to be different. He always described himself more as a promoter than a coach. He once told a reporter ‘I refused to slow down the game even when it helped the opponent. The crowd paid good money to see fast basketball. Why ruin it?’

When he retired from coaching the league entrusted him with two of the most critical roles for its development. Until his death in 1979 he was head of scheduling, utilizing his ingenious ability to figure out on which days revenue could be maximized. As a team owner-manager it was never beneath him to hit the streets selling tickets. His second role was even more historic – head of the rules committee. He did everything to encourage fast attractive basketball. When teams began using slow-down defensive tactics in the 1950s, he introduced the 24 second shot clock, without which it is difficult to imagine basketball today. The “Rookie of the Year” award – for the league’s most outstanding newcomer – is named after him.

He will of course not be the last Jewish coach to win the title. Red Auerbach did so nine times, Red Holtzman led the Knicks to two championships in the 1970s and Larry Brown is the only coach to win the professional and college championships.

And the Jewish players? They still had a role to play for many years. In its leagues second season, Dolph Schayes, a native of the Bronx, New York, 6ft 8in (2.03m) tall, and probably the greatest Jewish player of all times, entered the league. By the time he retired after 16 seasons he was the all-time leader in number of games, second scoring and third in rebounds. In the league’s 50th jubilee in 1996 he was selected from among the 50 best players of the half-century of play.

Schayes was starring in a league that was quickly absorbing black players and Jews also played a significant role in this process. Abe Saperstein, another Jewish coach-promoter, and good friend of Gottlieb’s, took over running the Harlem Globetrotters in 1928. Today the African-American team is known as a basketball trickery band but in its early years it was a legitimate competitive team. In 1948, when the Globetrotters reached 100 consecutive victories in tournaments and road trips, Saperstein and Max Winter, the Jewish owner of the Minneapolis Lakers, decided to hold a game between the teams. Saperstein and Winter did not see the event as a racial statement, but simply an attempt to find out who had the better team.

In front of 18,000 spectators in Chicago, the Globetrotters won 61-59 thanks to a last second shot by Elmer Robinson. A year later the Globetrotters defeated the Lakers again, who were now NBA champions, 49-45. The path for black players into to the league was paved. And that, of course, with all due respect to early Jewish contribution, was the game’s most historical turning point.