When and why did the matzos that we’re all familiar with become square-shaped? Seemingly, it’s easier to package them that way and perhaps even break off a piece if needed. But since when have convenience and logic characterized kashrut – Jewish dietary laws – or traditions associated with Jewish food?

Therefore, it’s hard to disagree about one thing: when our forefathers left Egypt and their dough did not have enough time to rise, it definitely occurred during an attempt to bake pita bread. Pita bread was round, as were regular matzos for hundreds of years, and so are most of the shmurah matzo that can be bought today.

The story begins in 1838 when a Jew named Isaac Singer from Alsace-Lorraine invented the first machine for baking matzos. Even though he shared the exact same name with an American inventor, the European Singer made a critical contribution to humanity in the form of the industrial production of matzos, whereas his American counterpart was engaged in much more trivial matters, such as inventing the sewing machine.

Rabbi Singer’s matzo machine did not perform all the steps of the matzo manufacturing process, but it did flatten the dough before it was placed in the oven – which made it much easier to complete the entire baking process within the 18-minute time frame stipulated in the Shulchan Aruch.

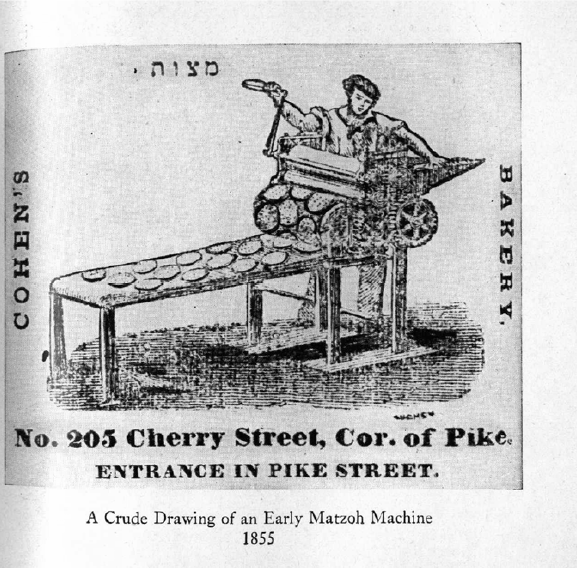

What did the matzos that came out of Singer’s machine look like? In an illustration from 1855, the machine is seen manufacturing round matzos ready for baking. At the time, the huge controversy surrounding whether the matzo machine was ‘kosher’ had not yet erupted. Rabbis from Germany and France – where the machine was in use – actually acknowledged its advantages, and in particular that it produced lower-priced matzos that the needy members of the community could buy. Traditional matzos were very expensive and oftentimes the poor could not afford them.

The trouble began when the machine traveled east to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and from there to Poland and Lithuania. One of the first people to voice his opposition was Rabbi Shlomo Kluger, known as the Marshak,, who wrote the following about the matzo machine: “And a fire shall burn within me and remain trapped in my heart should I see it spread among families like baldness, in the cities of Ashkenaz and also in our country which is still of superior quality.” Ashkenaz at the time referred to Germany – and Kluger / Ettinger was a Polish rabbi who bitterly lamented what he considered to be the low standards adopted in Ashkenaz.

Kluger’s ruling spread like wildfire and some Chassidic rabbis were even more adamant in their opposition to the machine. Rabbi Hayyim Halberstam of Sanz left no room for doubt when he wrote: “Matzo made using that machine is pure chametz.” The Rabbi from Gur not only condemned the machine, may its memory be blotted out, but also denounced anyone who used it: “as for what you asked about the Passover matzos made by a machine, etc., I agree with the ban and all the rest, and may G-d save his nation from those people, messengers of evil inclinations, students of Yeravam ben Nevat, who seek to chip away from each mitzvah a bit at a time, and their intent is to eradicate it all.” Which in layman’s terms means: those who bake matzos in a machine want to eradicate everything, and the matzo itself is no more kosher than a simple pita bread eaten on a regular day and it is chametz. Surprising, but true.

Ordinary readers of the Torah are probably wondering about the fast and furious intensity of the opposition. After all, it was not, G-d forbid, about eating pork, converting to another religion, ritual slaughter, Shabbat or licentious behavior. This was happening in the middle of the 19th century, when Chassidim were still in a head-to-head contest with Mitnagdim, reforms were in the making, and Zionism was just around the corner. And this is what you’re occupied with? A simple machine that makes matzo?

The arguments made by the most vocal opponents were of course based on Jewish law – whether it was the difficulty associated with cleaning the machine, or the fact that the integrity of the conscious intent behind the mitzvah of preparing the matzos could be undermined. The machine also jeopardized the livelihood of the poor people who worked in the bakeries where the hand-made matzos were made, who were employed at least a few days during the year. But the real problem with the matzo machine was something else. Even though it only flattened dough, the machine also produced a much greater threat in the form of the Haskalah – the Jewish Enlightenment movement. Namely, the fact that innovations could provide answers to everyday issues. Following an ostensibly small breach in the wall like the matzo machine, it would not take long for other innovations to emerge, such as hot plates for Shabbat, televisions, artificial limbs, and who knows what else – maybe even a robot that inspects the kosher status of the food instead of a mashgiach (a supervisor certified by the rabbinate)?

The machine also had quite a few supporters, including Rabbi Avraham Jener from Cracow, who wrote: “If the geniuses of our times were only familiar with the numerous obstacles to making matzos here in our city, and could see how the matzos are made using the machine, they, too, would rule that matzos should only be made using the machine.” Believe it or not, the dispute even divided families. Another supporter of the machine was Rabbi Joseph Saul Nathanson, the chief rabbi of the city of Lemberg (Lvov) and one of the most respected writers of responsa in his generation. He was also the Marshak’s brother-in-law. He issued the Annulment of the Announcement, which invalidated his brother-in-law’s ban.

Spoiler – innovation always wins. Let’s fast forward 30 years.

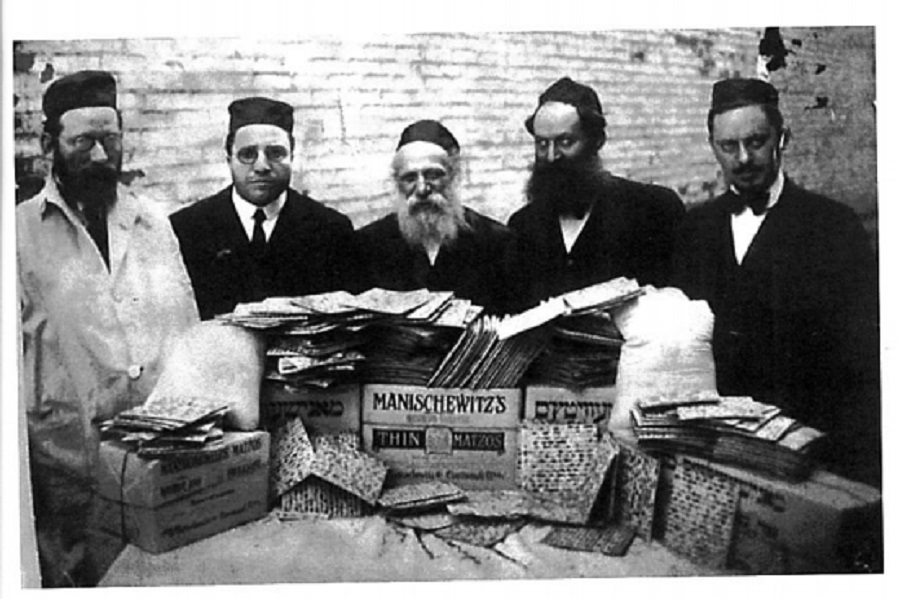

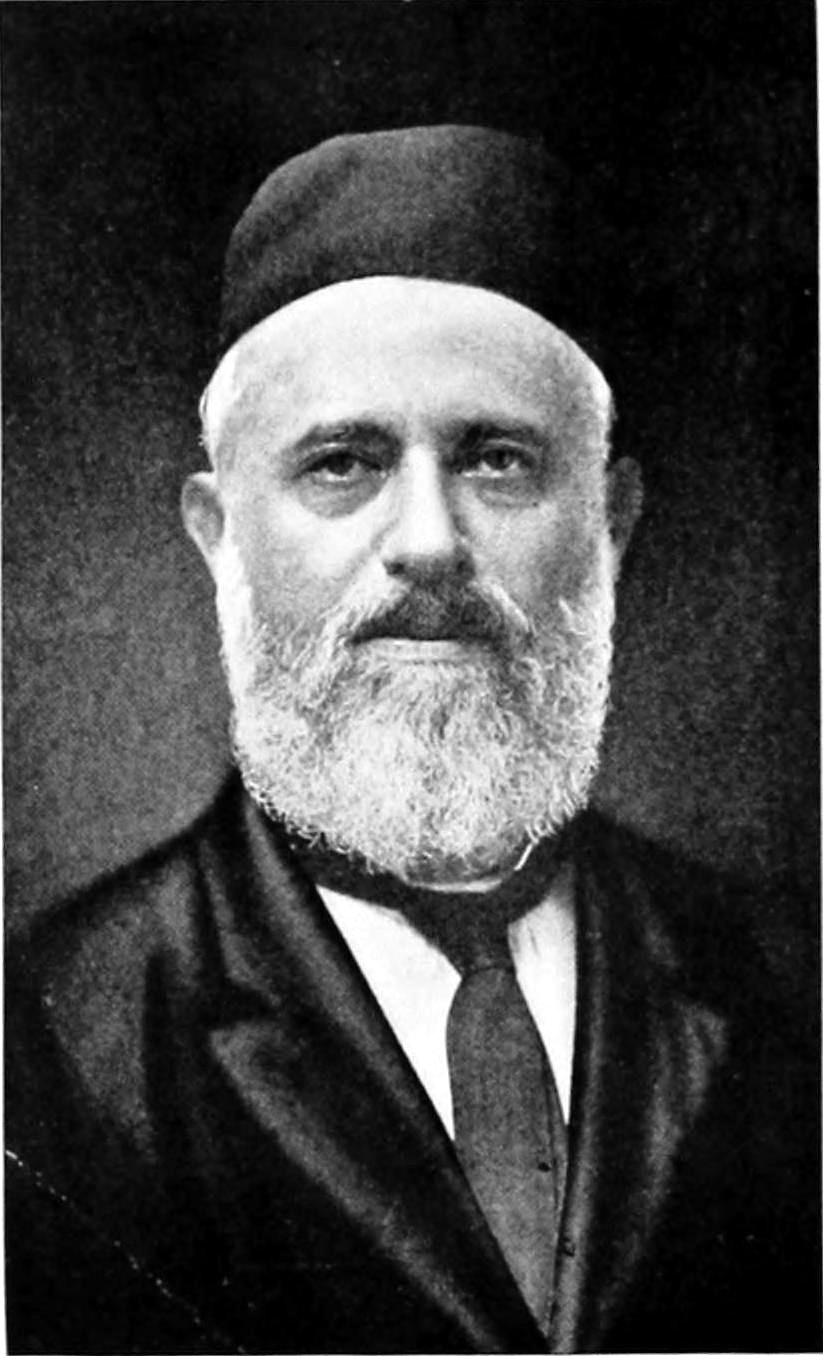

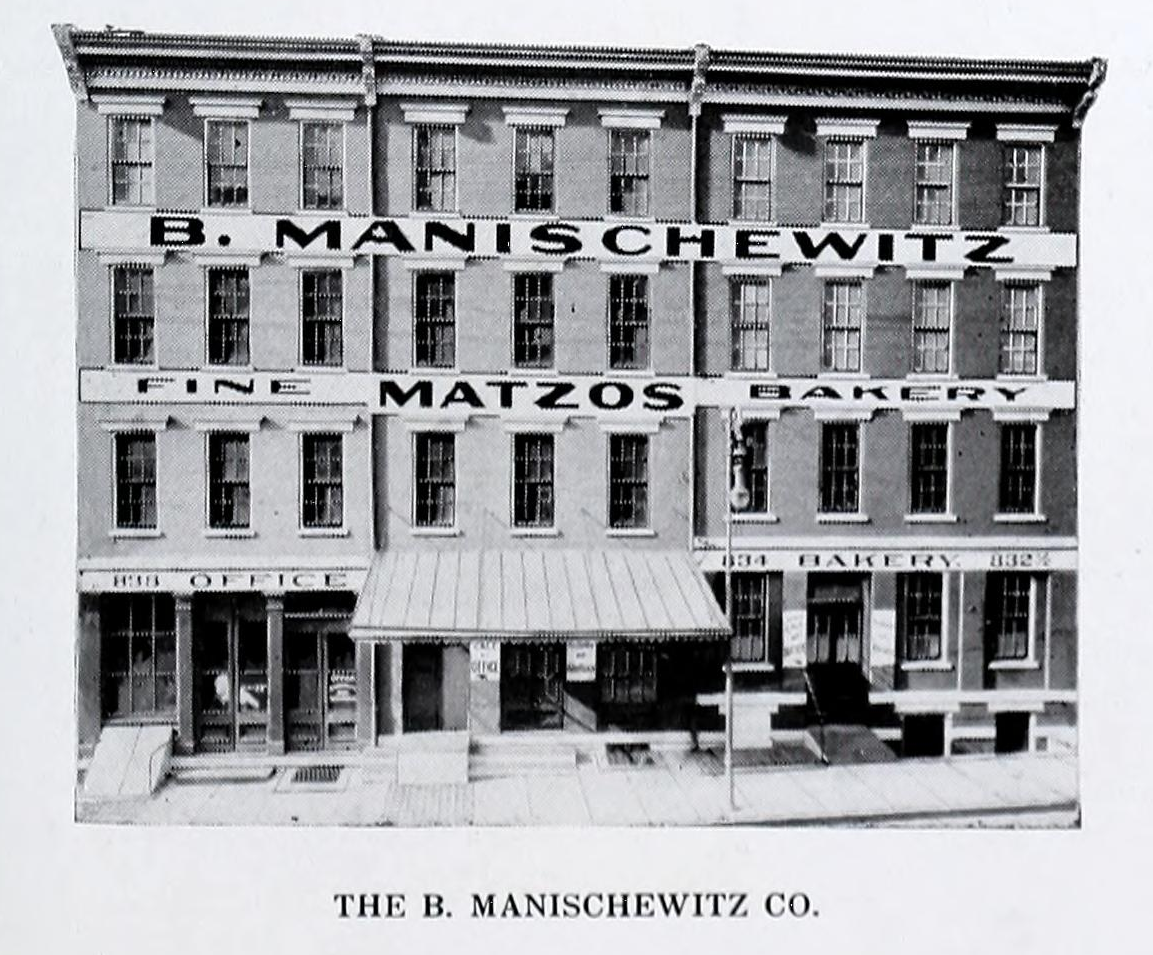

In 1886, a Jew by the name of Dov Behr Manischewitz emigrated to the United States from Memel (Klaipeda in modern day Lithuania). He was commissioned by the Jewish community of Cincinnati to be a shochet (a person certified to slaughter kosher animals). It was there that he would totally transform the Jewish-religious experience in America. He opened a bakery and started investing in technological inventions: one of them a machine for kneading the dough, and another one a gas stove that controlled the even distribution of the heat. In total, Manischewitz registered no fewer than 50 patents having to do with the manufacturing process – including a machine that counts matzos.

The baking of matzos is no longer a man-made craft. And if we go back to the question we asked at the beginning of the article, machine-made matzos can also be square and easier to package. Manischewitz spent most of his marketing budget on ads in Jewish newspapers published in English. He called his cutting-edge technology a “temple of kashrut.” But the message went much deeper: you can assimilate into American society, speak English, be in tandem with innovations, and still keep kosher.

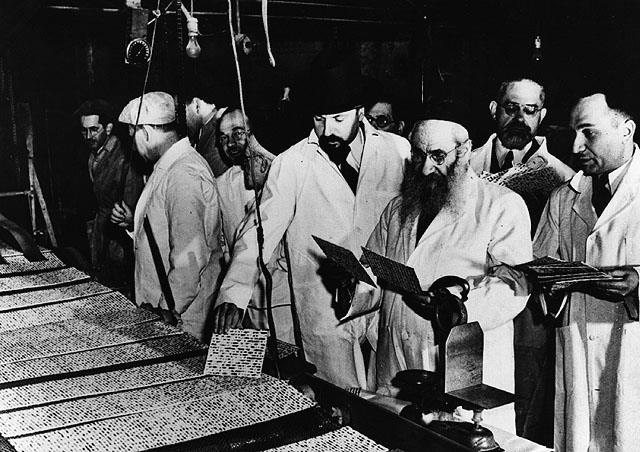

Manischewitz invited the most distinguished religious leaders of his generation to come and visit his bakery, regardless of their position on the disputed matter. He made sure that the visits were photographed, enabling him to publish ads in which America’s most eminent rabbis could be seen tasting his matzos and enjoying a good meal. Manischewitz also established the ” Manischewitz Board of Rabbinical Supervision,” whose members provided the company’s products with their kosher stamp of approval.

He took his public relations campaign outside the borders of the United States to the Land of Israel, where he funded charitable organizations and founded the Manischewitz Yeshiva in Jerusalem. In a successful attempt to expand his business beyond ultra-Orthodox Jews, Manischewitz received the blessing of Rabbi Kook, which turned the entire Zionist-religious community into his customers as well. A Manischewitz matzo factory was also opened in Givat Shaul in Jerusalem.

The money earned from the machine-made matzos injected cash into the rapidly growing business and enabled Manischewitz to branch out to wines (which became a familiar cultural icon, especially among American Jews), gefilte fish in jars, and every other imaginable Ashkenazi dish that could be mass produced. In the past few decades, the ownership of the business has changed hands a number of times. The company’s shares are currently traded on the stock exchange and its revenues are estimated at about $75 million a year. Today, Manischewitz is a household name among American Jews, but it is also part of popular culture where it is visible in various circles. And no less important – it is entirely synonymous with kosher food. Happy Passover!