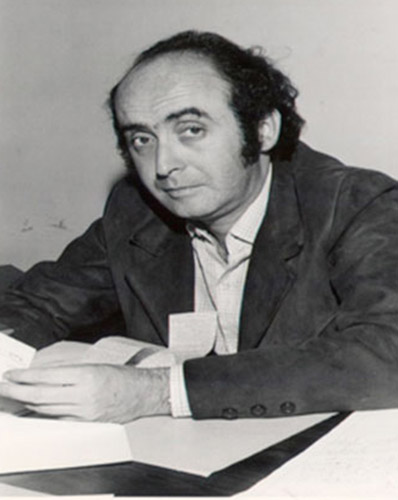

Rabbi Henry Sobel was a young rabbi in Sao Paulo, only 31 years old, when he was forced to make a decision that would define his life, and to a great degree would also impact the entire Brazilian nation. The year was 1975 and Sobel, the son of Jewish refugees who was born in Lisbon while his parents were fleeing the Second World War and were en route to New York, was in his fifth year as rabbi of a large Jewish congregation in Sao Paulo. And, then, the body of Vladimir Herzog was delivered to him for burial.

Herzog, who was 38 at the time of his death, was the head of the television journalism department at a TV network located in the city. According to the Political Division of the Intelligence Services, the cause of his death was suicide, which had allegedly occurred at an army headquarters near Ibirapuera Park. Sobel was given a highly amateur photograph of Herzog that was taken after his alleged suicide, showing that he had hanged himself with his belt. He had been questioned about his ties with the Communist Party, which was illegal at the time in Brazil under the military regime.

According to Jewish law, because Herzog’s death had been ruled a suicide, Sobel was obligated to bury him outside the gate of the cemetery. But the rabbi’s conscience kept him from doing so. Besides identifying signs of torture on the body, the rabbi had also heard that Herzog was the 38th reported case of suicide that had occurred during an investigation by the Political Division of Intelligence Services. But the previous 37 cases were less famous than that of Herzog. Furthermore, they represented only a fraction of the more than 400 people who had disappeared following their arrest.

In an act of defiance, Sobel decided to bury Herzog in the middle of the cemetery. As he saw it, Herzog was a Jew who had been murdered and had not committed suicide. Some members of the Jewish community opposed his decision because they felt it was dangerous to get involved in Brazilian politics, which at the time was a dictatorship and very intimidating. “I left the judging of the case to God,” Sobel said some years later.

Protests and demonstrations against the murder of political dissidents, or their sudden disappearance from the face of earth, occurred more than once in the early 1970’s. But according to the author Paulo Markun (himself a victim of torture), this was the turning point. It’s hard to know just how aware Rabbi Sobel was of the import of his decision and just how much it had trickled down to the Brazilian population as a whole.

A few days after Herzog’s burial, Sobel was asked by Archbishop Evaristo Arns to lead an interfaith service in the cathedral in memory of Herzog and for the ascent of his soul. A protest strike broke out at the University of Sao Paulo, drawing more than 30,000 students. 42 bishops signed a document demanding an investigation. Over one thousand articles in newspapers across Brazil demanded that the incident be investigated.

According to Paulo Markun, all of that was not in vain: Herzog was the last victim of a murder of a political dissident under the military dictatorship in Brazil.

Which begs the question: why did the Herzog affair, and not the others, bring about such a sweeping change? Just three years earlier, the Catholic Church led angry protests following the death of a young student named Alexandre Leme, the son of a privileged family. He, too, died after being arrested for political reasons. Those protests lasted a month, but did not cause the government to change its ways. Why, then, did the death of a Jewish journalist and the protest of a rabbi bring about the desired change?

Apparently, one reason was the political timing: a few months before Herzog was murdered, President Ernesto Geisel eased some of the repressive measures that had been imposed on citizens and their fear of the regime began to lessen somewhat. Because Brazilians were looking forward to a brighter climate, the shock and the rage were particularly strong. Another contributing factor was the botched attempt made by the security forces to cover up the case. The fake photographs lacked any shred of credibility. In fact, the cell where Herzog was held didn’t even have a high enough ceiling for a person to hang himself from.

Herzog’s persona also had a lot to do with the ramifications of the incident. Quite a few similarities can be drawn between his personal-family history and that of Rabbi Sobel. Herzog was also born in Europe, in Osijek, Croatia, in 1937 – which at the time was Yugoslavia. After the Nazis installed a puppet government in Croatia, the Herzog family’s property was confiscated and young Vladimir “Vlado” and his family fled to Italy. After Italy was conquered by the Allies, the family made their way to a camp for displaced persons in the city of Bari, and from there emigrated to Brazil. Vlado was eight years old at the time. His maternal grandparents were murdered in Auschwitz. His paternal grandparents were killed by Croatians in the Jasenovac concentration camp.

Brazil of the 1950’s and 1960’s experienced rapid economic growth and the story of the Herzog family was the story of many Brazilian Jews. Vlado’s father, Zigmund, worked as a bookkeeper, and his mother Zora, in addition to being a housewife, worked as a professional cook before entering the textile business. The prosperity and the freedom, as opposed to the darkness of their lives in Europe, created a genuine and strong bond between the Jewish emigrants and their new country.

Young Herzog was very thin and not the athletic type, but he excelled at school. People said that he urged and convinced his classmates to read European classics, especially ones written by Dostoyevsky. His parents tried to persuade him to major in the sciences, but he was not interested. Later attempts to find a low-profile, yet stable, job, like at an optical firm or a bank, also ended very quickly. When it came to making the choice that many of his generation faced – between professional success and idealism – Herzog’s decision was clear. He wanted to change the world.

Vlado studied philosophy at the University of Sao Paulo, after which his career as an arts and culture correspondent began. In parallel with his work as a journalist, he ‘crossed the lines’ and became a creator himself – he wrote a play and took part in making some important documentary films. In tune with his adopted homeland, one of the films that he produced – Subterraneos do Futebol – dealt with the importance of football (soccer) in Brazilian life as a vehicle for social mobility. It is interesting to note that two of Brazil’s football legends, Socrates and Romario, asked some years later that the head of the Football Association be investigated to ascertain whether he had any involvement in Herzog’s arrest and murder.

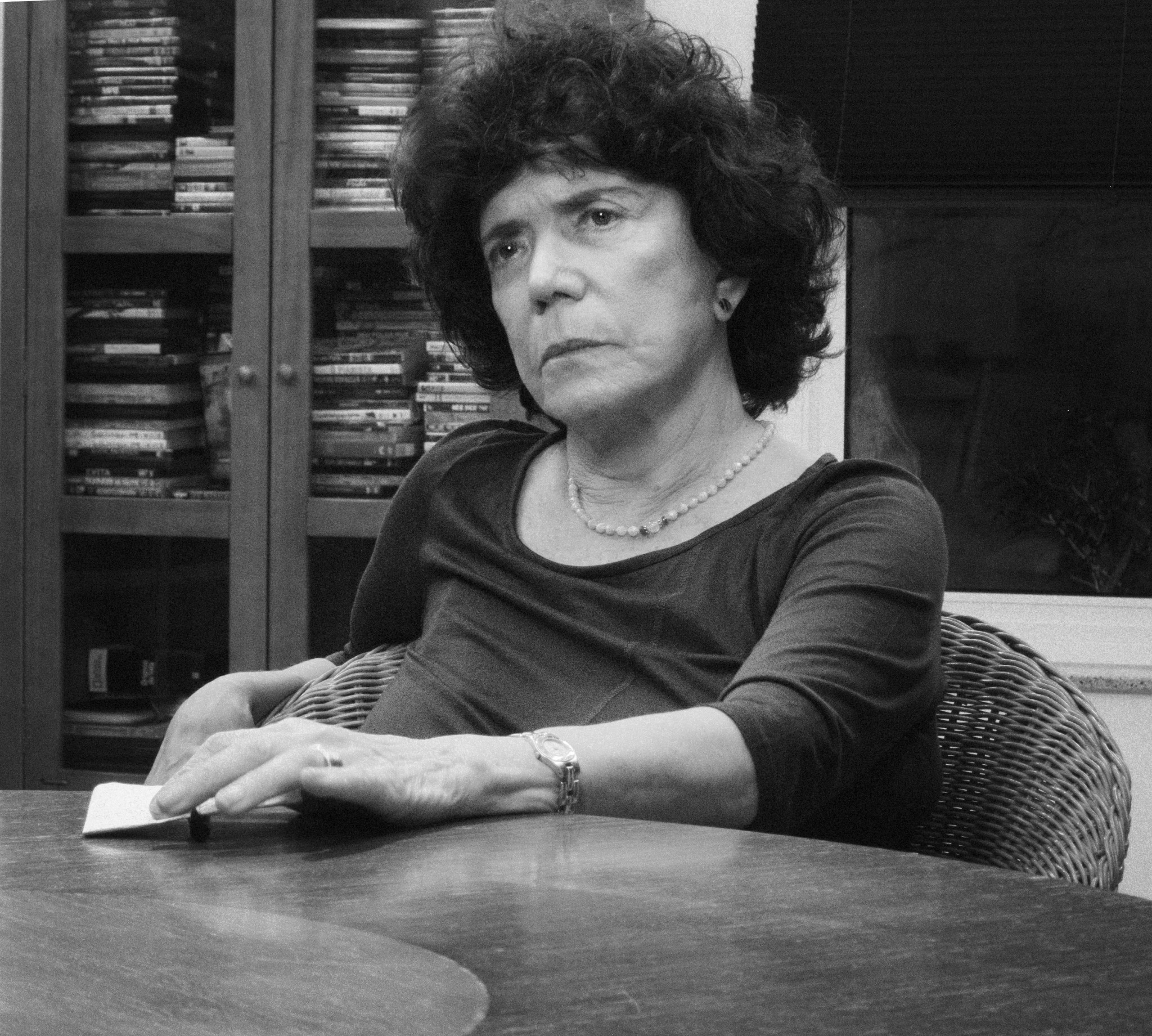

In 1964, two months after his marriage to an advertising professional named Clarice, Brazil’s democracy was replaced by a military regime, which remained in place for two decades. Vlado joined the circles of political dissidents, but at that point in time he had not yet become a major activist. He was actually given an opportunity to work for BBC News Brazil in London, where he ended up living for three years. While he was there, he took advantage of being back in Europe to take a month-long ‘roots’ trip to Yugoslavia and Italy – together with his family, including his two young children who were born in London. During his last months in London, he took a television production course that prepared him for a new television career which he embarked on after returning to Brazil.

Vlado Herzog began working as a professor of journalism at the University of Sao Paolo, and in 1975 was offered the job of his dreams – head of the television journalism department at TV Cultura, a television network that was a strange kind of animal in the media arena under the military dictatorship: it belonged in part to the Government of Sao Paolo, but demonstrated independence in its reporting. In his new position, Herzog managed to cover life in Sao Paolo from a different angle, while placing emphasis on the huge incidence of poverty in the city and the state. That type of reporting was highly unusual and rare for those times and it made him an object of admiration among the masses.

Nowadays in Brazil, Herzog is considered a hero and people credit him with expediting democratization processes in the country. But in real time, the regime of fear and informants instituted by the military dictatorship led some of his colleagues at the TV network to lodge a complaint with the authorities, claiming that Herzog was spreading communist ideas. After being called in for questioning, he came to the police station voluntarily on the morning of October 25, 1975. He even slept in his office to make sure that he wouldn’t be late for the investigation.

He was taken to an investigation facility on Rua Tomas Carvalhal, where he was tortured with beatings, strangulation, ammonia gas and electric shocks. Sergio Gomes, a journalist who was being held in an adjacent cell, reported the following in 1992: “I heard his screams from the investigation room: Who are those journalists? Who are those journalists?” He wanted the names of his colleagues who had betrayed him.

Herzog’s death triggered a wave of protests, strengthened the opposition to the military dictatorship in Brazil, sparked a storm in the international press, and galvanized the human rights movement in Latin America. The false account of Herzog’s murder and the attempt to rule it a suicide led to rage throughout the country. It was so widespread that even the then president of the republic, General Ernesto Geisel, claimed that Herzog had been killed by people he called “criminals.” As a first step, Geisel fired Ednardo D’Avila Melo, the extreme right-wing general who was behind what had happened.

Three years after Herzog’s death, his widow Clarice won a civil suit that she filed against the government. The federal court confirmed that his death had been unlawful and ruled that his family was entitled to compensation.

Herzog, who became a symbol of the struggle for democracy in Brazil, has been commemorated in many ways. The street in Sao Paulo that houses the TV network where he worked is named after him, and the Vladimir Herzog Institute was founded in 2009. Its aim is to preserve information and materials about him, promote the status of journalists, and award the Vladimir Herzog Prize to journalists and human rights activists.

In 2012, 37 years after his murder, a new death certificate was issued for Vladimir Herzog. It cites that he died “due to physical torture at the facilities of the Center for Internal Security Operations of the Sao Paulo Army.” Despite the considerable delay, justice has been served.