The author, Jonathan Safran Foer, wrote that “Jews have six senses. Touch, taste, sight, smell, hearing and…memory. While Gentiles experience and process the world through the traditional senses, and use memory only as a second-order means of interpreting events, for Jews memory is no less primary than the prick of a pin, or its silver glimmer, or the taste of the blood it pulls from the finger. The Jew is pricked by a pin and remembers other pins. It is only by tracing the pinprick back to other pinpricks – when his mother tried to fix his sleeve while his arm was still in it, when his grandfather’s fingers fell asleep from stroking his great-grandfather’s damp forehead, when Abraham tested the knife point to be sure Isaac would feel no pain – that the Jew is able to know why it hurts. When a Jew encounters a pin, he asks: What does it remember like?”

In his canonical work, Zakhor, the historian Yosef Haim Yerushalmi likened Jewish memory to a pain laboratory inhabited by ceremonies, rituals, traditions and customs, whose purpose is not to look for a causal explanation of past events, but rather is an attempt to draw meaning and significance from them. “Because of our sins we were exiled from our land,” the Jewish sages said, and not because we launched a revolt against a powerful empire that was doomed from the start. According to Yerushalmi, forgetting is the Jews’ archenemy, and so much so that the fear of forgetting is equal to the fear of death.

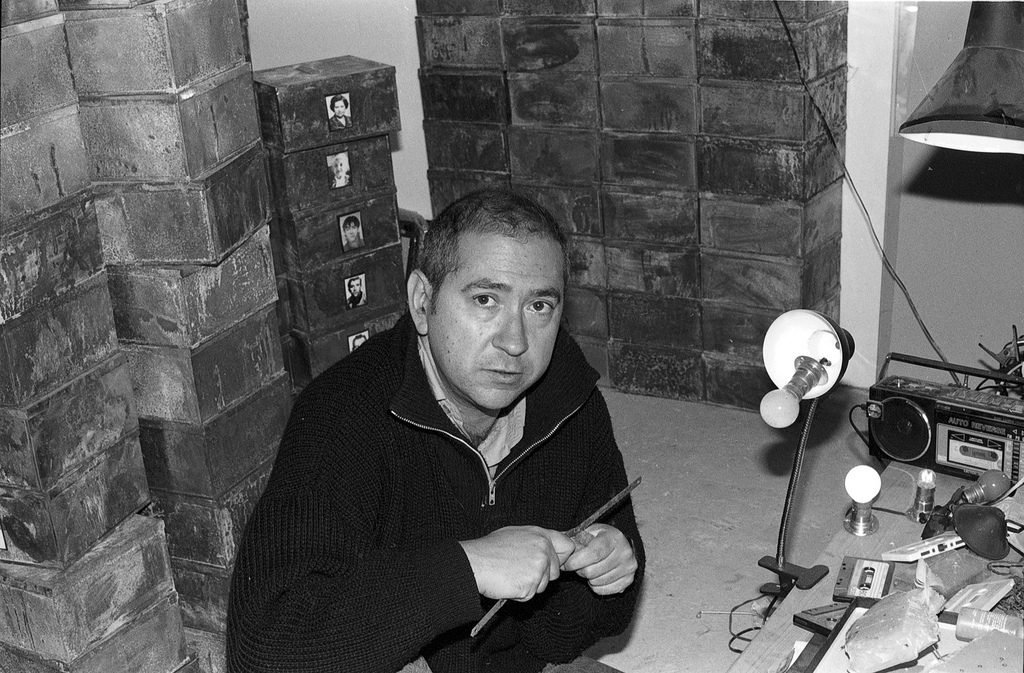

Memory, forgetting and death were the raw materials that preoccupied the artist, Christian Boltanski, who died last month in his home in Paris. His works are devoted to the war against forgetting and to a frantic search for the significance of memory and the fragility of life. Boltanski – one of the world’s most eminent artists in recent decades – attributed all this to his Jewish father, who during World War II hid under the floorboards in his house for eighteen months. “I believe that every artist is driven by some kind of trauma, and the Holocaust is my trauma,” Boltanski said in an interview. “I was born to a Catholic mother, but if asked I’ll say that I’m Jewish, even though I’m a nonbeliever. I’ve never been inside a synagogue, but feel that I am a son of the Holocaust. I can connect with the Jewish story because of my family’s story and all of my parents’ friends who were Holocaust survivors.”

As a boy, Boltanski was afraid to walk the streets of Paris on his own and for that reason left school at the age of 13. He completed his studies at home, describing his family as being “crazy,” but in a good way of course. After his brother complimented him on a doodle casually drawn on a piece of paper, he decided that he was an artist. His parents encouraged his emerging talent and provided him with all the necessary supplies. Boltanski’s rise to fame was meteoric. Right after graduating from L’École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris – which is one of the most prestigious art schools in the world – he had a solo exhibition. And from there, the road to global success was short.

Boltanski took his personal trauma – the Holocaust – to universal places. In the numerous exhibitions he had around the world, you could never find the usual objects associated with the memory of the Holocaust. Rather, his commemoration is conceptual, where the particular and the universal merge together to form an emotionally powerful work. An example can be found in the Nevzlin Art Collection at ANU – Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv, where Inventory, a work created by Boltanski in 1989, is on display. Comprised of 54 old tin cans, the work is reminiscent of an altar-like structure. An enlarged photograph of a high school student hangs above the “altar,” which originally was part of a class picture taken at a Jewish school in Vienna in 1931. Boltanski enlarged the photograph and placed a small lamp over it. Whenever the light hits the student’s forehead, it looks like a bullet wound. The anonymity of the Jewish student, who was probably killed in the Holocaust, pushes the viewer’s emotional buttons, making it impossible to separate the feeling of sadness and sense of loss that the student evokes from the horror associated with the way his life ended.

Boltanski’s art deals with the transience of anonymous life and the desperate attempt to give life meaning despite its inherent banality. “Every one of us is special and important,” he said. “Nonetheless, we are destined to disappear. Most of us will be forgotten within two generations, after those who knew us die as well.” From his perspective, the Holocaust was an example of a collective death that left no personal mark. He therefore made use of it to convey a universal message. “People who are unaware of my interest in the Holocaust are able to see something else. And I want them to see something else.”

As someone who cast himself in the role of the Don Quixote of memory, battling the windmills of forgetting, Boltanski was a compulsive collector who took no break from his Sisyphean war against forgetting. He collected everything: threads, fabrics, cans. He had a huge archive of one million photographs, and even one of heartbeats. For real. His Heart Archive is installed on the island of Teshima in Japan, where tens of thousands of recordings of human heartbeats are already housed – and their number continues to grow. At his exhibitions, Boltanski installed recording studios where visitors were welcome to add a recording of their own heartbeat to the collection. Here, as well. Every heart symbolizes a world unto itself. But it becomes anonymous as soon as it coalesces with the universal human heartbeat.

About three years ago, Boltanski had an exhibition at the Israel Museum. It was called Lifetime and spanned 30 years of his prolific career. At the entrance to the exhibition, there was a stopwatch that showed how much time had elapsed since September 7, 1944 – the day on which Boltanski was born. When Boltanski closed his eyes for the last time, the watch was also supposed to stop ticking.

A little more than a month ago, on July 14, 2021, Boltanski’s heart stopped beating and the watch stopped ticking. His fate can be compared to that of Funes, the unforgettable character in Jorge Luis Borges’s story, Funes the Memorious. Funes is unable to forget anything, including the most trivial thing, until he finally collapses under the weight of his memories and dies. The same holds true for Boltanski, the artist who devoted his life to the war against forgetting. He, too, collapsed and died under the weight of his memories.