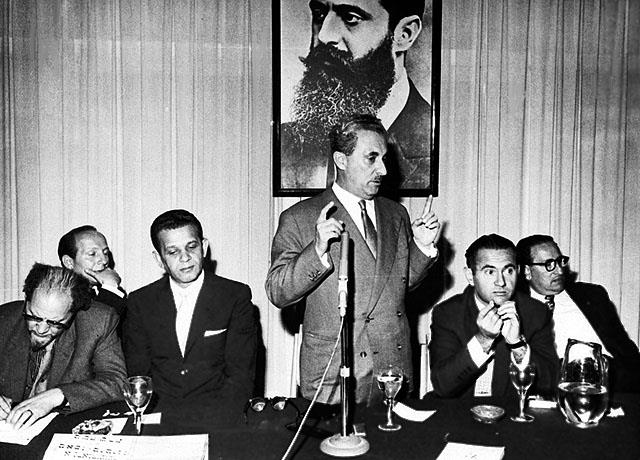

The evening of January 23, 1963 marked the start of a public trial held by the Jewish Agency against the Algerian Jewish community. Over 100 men and women crowded into the auditorium of the Jerusalem Artists’ House, where the key charge leveled against Algerian Jewry was their alleged flawed Zionist sentiment.

The person behind the trial and its architect was the then Chairman of the Jewish Agency and former Prime Minister, Moshe Sharett. He was maddened by the fact that out of 140,000 Algerian Jews, only 15,000 had emigrated to Israel, while the others preferred to emigrate to France. “That choice reflects their estrangement from Judaism and disregard for the State of Israel,” said Sharett.

Professor Shalev Ginossar from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who held the esteemed title of President of the Court, was quick to follow suit. He argued that “this community (Algerian Jewry) had already fled from one place of exile, and instead of learning the lessons of Jewish history, chose another place of exile over their national home – the State of Israel.” The highly charged deliberations lasted from the early evening hours until close to midnight. There were some dramatic moments, such as a failed attempt to prevent a group of Algerian Jews (employees of the Nuclear Research Center in Dimona) from entering the auditorium, who came there to protest the trial.

Goodness gracious. How did such a major error in judgement occur? Weren’t Algerian Jews smart enough to see the Zionist light when they chose Paris, the City of Lights, over Israel? The Sorbonne over the Hebrew University of Jerusalem? The Place des Vosges over Kings of Israel Square in Tel Aviv?

But the more interesting question is why did Moshe Sharett unleash his fury at Algerian Jews and not, for example, at Jews living in Britain, the United States, Holland or South America, who emigrated to Israel in much smaller numbers?

The explanation lies in an imperfect understanding of the reality in which Algerian Jews lived – owing to a combination of ignorance and Ashkenazi elitist arrogance. In the eyes of Sharett, Algerian Jews were part of the ethnic subgroup that the research typically refers to as “Jews from Muslim countries.”

Sharett’s disappointment over the low rate of immigration stemmed from an expectation that Algerian Jews would be like most of the “Jews from Muslim countries” – Morocco, Tunisia, Iraq and Yemen – and emigrate to Israel in masses. In his capacity as the ruler of “First Israel” (the privileged class), the former Prime Minister was blind to any other option. As Edward Said would probably have put it, he suffered from patronizing Orientalism. Whoever is familiar, and even a little, with the story of the Algerian Jewish community knows that its cultural and social characteristics should be compared not with those of Moroccan or Tunisian Jews (with all due respect), but rather with those of Jews living in the Western countries mentioned above.

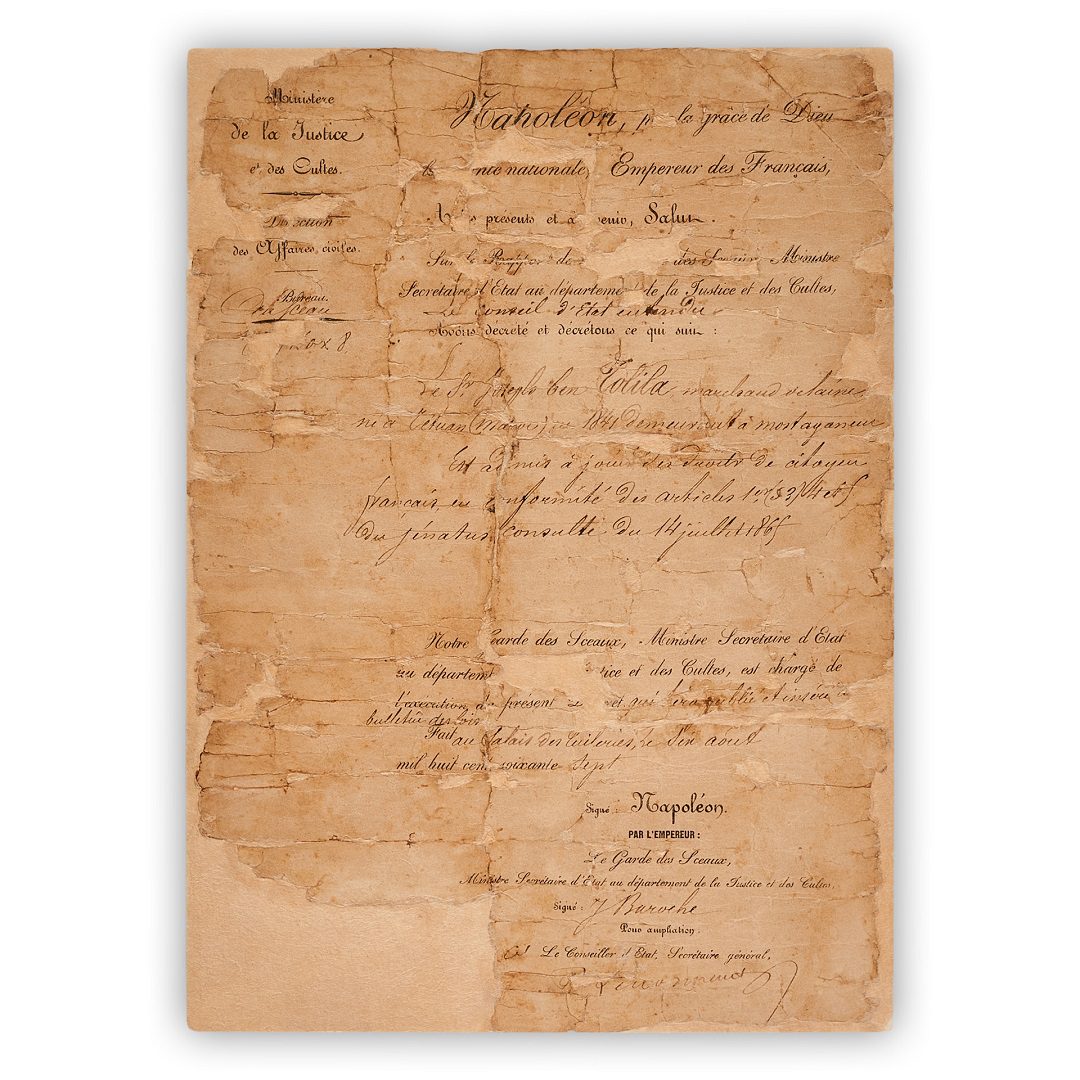

The original Letter of Rights issued by Napoleon III to a Jew named Abraham Bentolila is on display at the new ANU Museum. Bentolila’s brother was the great-great-grandfather of none other than the television personality, Erez Tal, who also narrates the story during the highlight tour on the Museum’s audio guide.

The Bentolilas were originally from Toledo, Spain. Following the expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula, they settled in Tetouan, Morocco and from there made their way to Algeria. It is believed that because they were fluent in a number of languages – Arabic, Spanish and French – the members of the Bentolila family became expert interpreters. That possibly also provided the backdrop for the issue of the Letter of Rights. As the leader of the French Empire that ruled Algeria, Napoleon III needed professional interpreters to mediate between the colonial French government and the local population.

Furthermore: the Letter of Rights given to Abraham Bentolila by Napoleon III was issued around the middle of the 19th century. That was before German Jews were granted full and equal rights, and surely before Jews living in Russia or in other Eastern European countries received them. In this regard, Algeria’s Jews were the exception. As early as 1865, many of them were granted equal rights, and in 1873 they officially became full French citizens. That occurred as a result of the Crémieux Decree (named after Adolphe Crémieux, the Jewish-French Minister of Justice). It was a remarkable precedent that none of the Jewish communities in North Africa, nor the majority of Jews worldwide, benefited from at the time.

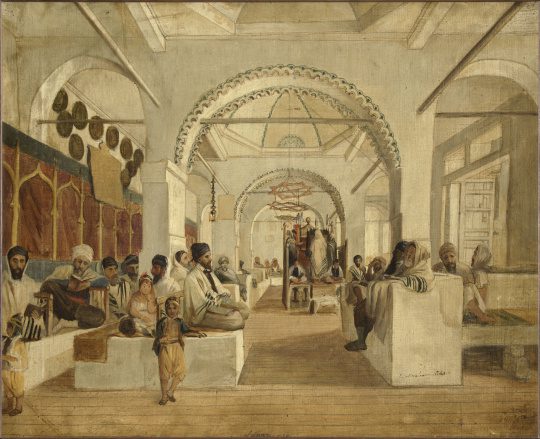

In his enlightening book “Algerian Jewry During the French Period,” Professor Yossef Charvit describes in detail how the early emancipation of Algerian Jews made them more French than the native Frenchmen, and it only took two decades. The rapid transition from Muslim rule to French rule dazzled them. They were enchanted by the luster and the etiquette, the ceremonialism and the French discipline. They quickly abandoned their Judeo-Arabic language for French, adopted French fashions, changed their names to French names, and acquired a broad-based education at private schools where French was the sole language of instruction.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Algerian Jews made up a disproportionately high percentage of the white-collar workforce – they were lawyers, physicians, engineers, government workers, senior officers in the French army, etc. Their identification with French culture also manifested itself in works of literature and poetry written in French by Jewish Algerian poets and authors. A number of women were prominent in this field in the early 20th century, including Elissa Rhais, Berthe Bénichou-Aboulker and Blanche Bendahan (whose life stories are recounted in the Women Trailblazers section of the Museum).

According to Professor Charvit, the public trial against Algerian Jewry, which ended with a whimper, underscores how little the Israeli elite understands the multiple identities that Algerian Jews live with – they are Sephardi Jews, but at the same time also Frenchmen, and also products of the West and the East, and also secular and traditional in their religious views. Algerian Jewry is unique. For that reason, Professor Charvit believes that the public trial held by the Jewish Agency against Algerian Jewry – the only public trial ever held by the Zionist movement against a Jewish community– is a badge of dishonor. It was not the Algerian Jewish community that should have been put on trial, but rather the Jewish Agency itself.

Professor Charvit also shatters the myth that Algerian Jews were not Zionists. As he sees it, because the Jewish community in Algeria had Western features, likening it to Jewish communities in North Africa is an unfair comparison. Rather, it should have been compared with other Jewish communities in the West, as opposed to which the emigration rate of Algerian Jews to Israel would be considered one of the highest.