Rabbi Chanoch Heinich HaCohen, once told a story about a fool who didn’t want to go to sleep because he was afraid to take his clothes for fear of not finding them the next morning. So, what did he do? He took a pencil and paper and wrote down where he had placed each and every item of his clothing: the streimel is on the right side, the trousers are on the left side, the shoes are over there, and so on. When he woke up in the morning and wanted to find his clothes, he read what he had written down: the streimel is on the right side, the trousers are on the left side, and the shoes are over there, etc. etc. And then he asked: “But where am I?” Because he was looking for himself in his bed.

If the security situation permits, this coming Sunday Israelis will don their holiday clothes and as many Leil Tikkun Shavuot events as you can imagine – namely, study sessions held on Shavuot Eve – will sweep Israel’s streets and cities: whether a secular-Jewish tikkun or a religious-Jewish tikkun, a tikkun in the spirt of Chassidism or a tikkun in the spirit of sustainability, a tikkun organized by the Reconstructionist Judaism movement or a tikkun organized by the long-standing Judaism movement, a tikkun marking a collective awakening or a tikkun marking individual lethargy.

The question is whether like the fool in the Chassidic story, we, too, will wake up in the morning and ask ourselves: “Okay, we’re wiser, we studied, we’re more knowledgeable. But where am I in all this story?

In this brief article, we will try and show how the nature of the Shavuot holiday has shed and assumed new forms throughout Jewish history, in line with the changing circumstances and the zeitgeist of the period in which it was celebrated.

Initially, Shavuot was a wheat harvest festival. Prior to the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, Jews in ancient times would bring the first sheaves of their wheat harvest to the Temple. In our romantic collective imagination, we can see masses of people going to the Temple with baskets of newly harvested produce, brimming with all the best that the earth yields – fruits and vegetables, grains and various sweets. But the truth is that the baskets only contained two challahs, which were baked with seeds from the first wheat harvest, namely the first fruits of spring.

Following the destruction of the Second Temple, the Jews were dispersed in the Diaspora and the land was abandoned. When on the morning of the destruction the Sanhedrin sages found a note left behind by their forefathers, which included instructions about how to bring the first ripe fruit to the Temple on Shavuot, they rightfully maintained: But where are we in all this story? So, what did they do? They changed the focus of the festival from the earth to man and from space to time. And when we say “time,” the intention is to a particular date – the 6th of Sivan – which according to Jewish tradition is the date on which the covenant was established on Mount Sinai. Consequently, starting in the second century A.D., Shavuot went from being an agricultural festival to a national holiday.

In the early part of the Middle Ages, the center of Jewish learning shifted from Babylonia in the East to Muslim Spain in the West. It was during that period, which is also known as the Golden Age of Spain, that one of the greatest works was written – the Book of the Zohar.

The Book of the Zohar is a mystical enigma comprised of geological layers of symbols and allegories. According to the kabbalists of Spain, which they revealed to us in a moment of divine inspiration, what we read in the Old Testament is merely an indicator, a display window leading to a deep and highly meaningful signpost. Abraham, for example, is not only a tangible figure who had a place in history. Rather, he is also a “sefira” – a kind of Jungian archetype – who represents a mythic-spiritual power of the abundance of divine grace. One of the key images in the mystical menu of the Zohar is the erotic image. As described for us in the Zohar, the world of divinity is a sexual-spiritual arena, where powerful male and female forces clash with the eternal Eros-Thanatos relationship. It reached a peak at Mount Sinai, when the holy union between G-d and the Jewish people took place, a marriage covenant that symbolizes the apex of monotheism – the perfect union of the cosmos.

The wisdom of the Zohar reached the Land of Israel in the 16th century, after being adopted by the Safed kabbalists headed by Joseph Karo, the author of the Shulchan Aruch, and Rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz, the author of the Lecha Dodi liturgical poem, and later by a group of kabbalists who were followers of the Ari (Isaac Luria). Even though that group of sages was active for only a short time, their impact on Jewish philosophy was unprecedented. Under the leadership of the Safed kabbalists, Shavuot underwent another transformation. The 6th of Sivan went from being a date of national importance to one of spiritual-religious significance, embodied in the ritual of Tikkun Leil Shavuot. In Aramaic, tikkun means decoration. Because according to the Book of Zohar the mystical union between G-d and the Jewish people took place on the 6th of Sivan, we must adorn the bride – the Jewish people – by studying Torah all night long on Shavuot. That way the bride will be beautiful and elegant at her marriage ceremony with G-d held the next morning. The Shavuot holiday, which began as an agricultural festival and after that became a national holiday, now received a mystical-religious dimension. Three layers, Three identities.

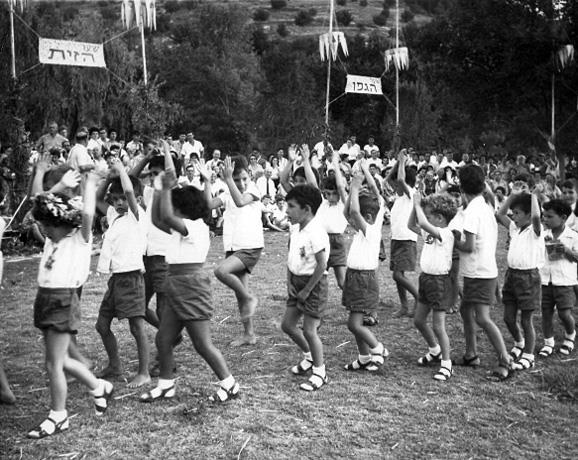

A fascinating thing occurred following the return to Zion in modern times and the emergence of the Zionist movement. The kibbutzim and agricultural communities restored Shavuot’s ancient glory and it reassumed its original character – namely, that of an agricultural festival. The time and the space merged again, but the holiday now had an added national layer that was missing the first time around. However, even more interesting is the fact that in recent decades the nature of Shavuot as an agricultural festival, which symbolizes Israel’s national strength, has been abandoned and discarded in the dustbin of history. And, surprisingly, Tikkun Leil Shavuot, which has mystical-religious origins, has become the main focus of the holiday.

The transformation of Shavuot from an agricultural-national festival to a religious-spiritual one is thought provoking: Does it reflect the disavowal of national ideas by Israeliness? Are we witnessing a new spiritual-religious quest among Israelis? Or, perhaps, is the Shavuot holiday in Israel of 2021 a litmus test of our fragile, and mostly confused, identity? Just like that fool who got up in the morning and started looking for himself.