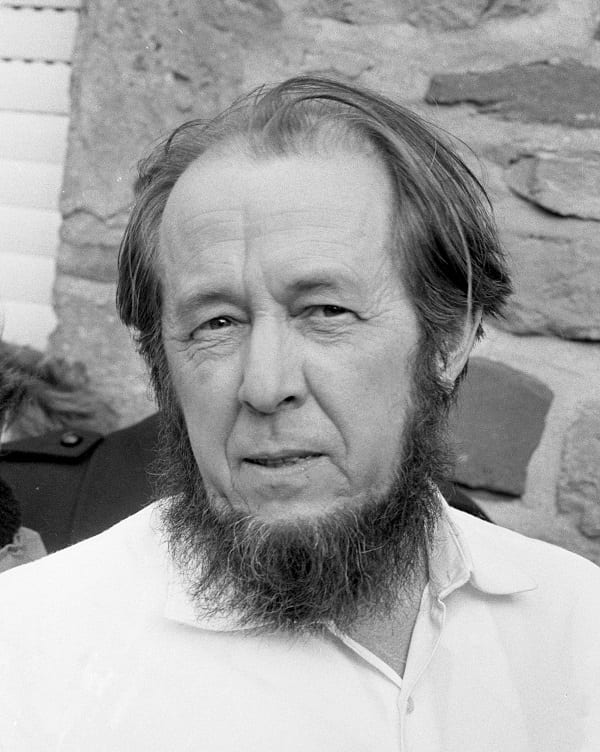

The “Demon of the Archipelago” is how the historian, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, described Naftaly Frenkel, the man who started out as a common prisoner in the gulag and became the big boss of the Soviet forced labor camps. He also conceived the idea of the “nourishment scale” – the barbaric labor system that was in place in the gulags.

Solzhenitsyn, the Nobel Laureate in Literature who was exiled from the Soviet Union, knew all too well what he was talking about. He played a pivotal role in exposing what was going on in the Soviet labor camps (gulags) to the Western world.

So, who was Naftaly Frenkel, that “Demon of the Archipelago”?

Facts about Naftaly Frenkel’s childhood are vague. Some sources claim that he was born in Haifa in 1883 and during the great famine that afflicted the country in the early 20th century, he emigrated with his family to other locations along the Mediterranean to escape hunger. According to Solzhenitsyn, Frenkel was a “Turkish Jew who was born in Constantinople.” Other accounts describe him as a Hungarian industrialist. In any event, his Hebrew name reveals his Jewish ancestry. Furthermore, in Soviet records, he appears as Naftaly Aronovich, which probably means that his father’s name was Aaron.

In his adult years, he established himself as a successful businessman in Odessa, where he traded in whatever goods he could get his hands on, including timber and weapons. He even owned a local newspaper. His acquaintances described him as an innate trader. He had a keen sense for business, as well as impressive managerial and organizational skills. In the years following the Bolshevik Revolution, Frenkel continued to be very successful in his business dealings thanks to the ‘soft’ Marxist economic policy, known as the New Economic Policy (NEP), under which small and private businesses could be opened in Odessa.

At the time, there were no early signs of his Mephistophelian character, which would later enable him to assume a position of leadership in the Soviet government. Nor were there indications that he would maintain personal ties with Stalin and become the architect of the death of tens of thousands of prisoners from hunger.

The first twist in Frenkel’s path to becoming a human monster occurred in 1923. Together with nine other people, he was arrested by the Soviet authorities and sentenced to death for “illegally crossing borders.” But right before his execution, his sentence was unexpectedly commuted to ten years of hard labor, whereas the other prisoners with him were shot to death. The rumors say that Frenkel bargained for his life with the local commandant. Whatever the case may be, Frenkel was not executed, but rather was sent to the Solovetsky labor camp in northwest Russia, which was one of the first forced labor camps in the USSR.

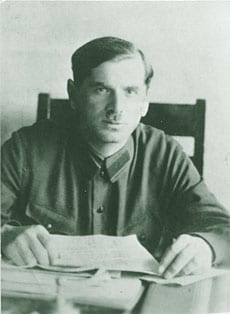

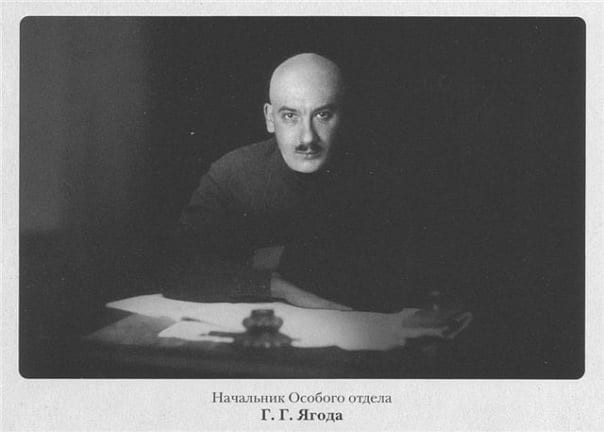

After arriving in the Solovetsky labor camp, Frenkel was surprised to find that utter chaos, inefficiency and wasted resources prevailed there. For some reason, the corruption and state of disarray bothered the Jewish businessman from Odessa, who displayed resourcefulness and decided to take action. After devising a detailed efficiency plan, Frenkel put it in writing and placed the letter in the prisoners’ complaint box in the camp. Against all expectations, the letter made its way to Genrikh Yagoda, a bureaucrat in the secret police who later became the founder and director of the NKVD (Yagoda, by the way, was also Jewish). He was enthused by Frenkel’s ideas and summoned him for a conversation.

In a flash, Frenkel went from being a nobody to a somebody, and the disenfranchised prisoner sentenced to hard labor was appointed the chief of works at Solovetsky. The first step that Frenkel took was to cancel the distinction between ordinary criminal offenders and political prisoners. He did away with the unprofitable agricultural work at the camp and discarded the re-education initiatives – all in favor of pure productive labor in the form of building roads and timber mining. Under Frenkel’s management, output became the only principle that mattered in the camp. The reward – was food, and the system – was simple and cruel. Whoever managed to produce more than his daily work quota received an added portion of food. And whoever produced less – his portion of food was reduced.

Frenkel divided the prisoners into three categories: prisoners who were capable of heavy labor, prisoners who could do light labor, and prisoners with disabilities. Each group received a different set of tasks and quotas that they had to meet, and were fed accordingly. There were drastic differences between the prisoners’ portions and their fates. Over time, the able-bodied prisoners survived longer, and the weak ones became even weaker and died of hunger. If you like, it was a Hobbesian jungle at its best. It also poked a finger in the eye of an ideology that started out as the Marxist utopia of “from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs,” and ends with a “Frenkelian” dystopia of “each according to his abilities, and whoever is unable – can drop dead.”

Frenkel’s system was a huge success and was adopted by other forced labor camps. It was soon given the name “nourishment scale” – or the “you-eat-as-you-work” system. The rumors about the prisoner who climbed up the Soviet hierarchy thanks to his extraordinary logistical abilities also reached the supreme leader, Stalin, who ordered Lazar Kaganovich, his friend and confidante, to summon Frenkel to a meeting. Stalin was impressed by the Jewish entrepreneur, and at the end of the meeting he appointed Frenkel to be manager of the government’s flagship project: building the shipping canal that was supposed to join the White Sea and the Baltic Sea in northwestern Russia, not far from modern-day St. Petersburg.

Frenkel managed the project with great skill and within a matter of two years, in 1933, the construction of the 227-kilometer canal was completed in record speed. For purposes of comparison – it took 19 years to build the Panama Canal, which is 81.6 kilometers long, and 10 years to build the Suez Canal, which is 162.5 kilometers long. The cost was a marginal issue, mere grease on the wheels of the revolution – over 12,000 prisoners died during the construction of the canal (out of a total of 250,000 laborers).

Testimonies have described Frenkel as being power hungry and heartless. The former businessman from Odessa would walk around the camps dressed in a perfectly pressed military uniform, with a walking cane and a “sinister Hitler moustache.” Others recalled that he had a phenomenal memory and impressive computing skills. They said that Frenkel would walk around without pencil or paper because he simply remembered all the data given to him out in the field by heart. He would later return to his office and dictate the figures to his secretary, while doing all the complicated mathematical computations in his head unassisted.

Naftaly Frenkel lived until a ripe old age and died in his apartment in Moscow in 1960. He survived the great purges of Stalin and the persecutions against the Jews that were widespread at the beginning of the 1950’s. According to rumors, every time he was suspected of treason and his name would come up in Lubyanka, the headquarters of the KGB, Stalin would personally intervene on his behalf.

Frenkel made a huge contribution to the Soviet murder machine, and those who claim that the gulags would have existed even without him, need to remember what Solzhenitsyn wrote, who was the most prominent documenter of the atrocities perpetrated in the gulags: “It would seem that there had been camps even before Frenkel, but they had not taken on that final and unified form which savors of perfection.”