Not only in these trying times, but in the 16th century, the Italian region was the site of a “fatal virus.” Catholic scholars knew the invader well. They “studied” it for 1,500 years, and knew how to identify it from more than two meters away. They heard the primal story for generations – from father to son and mother to daughter: How the devious “plague” – the Jewish People – murdered their ancient Father and Savior and left him bleeding to death on the cross. The Christian leaders did not admit it, but in their hearts, they knew that they were a mutation of the same “virus.”

Jews had lived in Italy since the days of the Roman Empire. In the late Middle Ages, many of them began pouring into the Land of the Boot following their exile from France and continued oppression under various princedoms in Germany. Most of them journeyed east to Poland, where a mammoth Jewish civilization came into being. But some of them settled in Italy. Their numbers in Italy grew significantly in the early-16th century, following the exile from Spain in 1492. Tens of thousands of Spanish exiles settled in Italy and other Mediterranean countries.

On those days, Italy was not the sovereign nation that it is today. It was a region divided into city-states: Florence, Pisa, Genoa and the hero of our story on the Adriatic Sea, Venice.

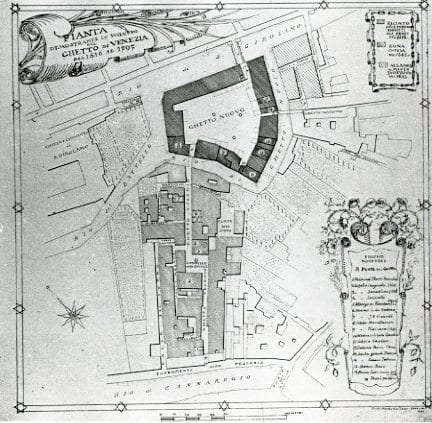

On March 29, 1516, 504 years ago, the Doge of Venice issued an order to create the first Jewish ghetto in history. Jews had been permitted to enter the gates of the city during the day to do business, but were forced to leave at sunset. To facilitate containment of the “virus,” authorities allowed Jews to live in the city – as long as they remained on a remote island far from the city center. The island – the site of a former lead foundry – was called in Italian “Ghetto.” That has since become a generic name for a separate, walled-off neighborhood designated for a specific population.

We have no idea which Italian played the current role of the Israel Health Ministry’s Moshe Bar-Siman Tov, but we do have the orders issued by the captains of the “Catholic Health Ministry” to prevent the spread of the “virus”:

- Exit from the ghetto is only permitted when the morning bells ring in St. Mark’s Basilica and until midnight.

- Exit from and entry to the ghetto is permitted only through two gates and under the supervision of four Christian guards, whose salary will be paid from the Jewish community’s coffers.

- Jewish money-lenders are permitted to leave for the city during limited hours and while wearing a yellow patch on their cloaks. The yellow patch was later replaced with a yellow hat, and then with a red hat.

- The following trades are permitted to Jews: Physicians, moneylenders, merchants, and used-clothing sellers – known in local jargon as “strazzarioli.”

Historians differ as to whether closure of the ghetto created a relative severance of cultural relations between the Jews and the rest of the population. Some maintain that it was actually a stage in their acceptance in the fabric of European life. Either way, the first ghetto dwellers in history adhered to the biblical principal that “It is a people that shall dwell alone and not be reckoned among the nations” (Bamidbar 23:9) – and they were undaunted by the limits imposed on them. They quickly began to develop a unique and independent culture that marked superb achievement in rabbinic

literature and commentary. Newly clustered in the ghetto, they established synagogues known as “Scole” and each ethnicity founded its own house of worship.

The Jewish community exported many scholars and schools of thought. One of the Venice Ghetto’s best known and colorful characters was Rabbi Yehuda Yehuda Aryeh of Modena, who was active in the city in the first half of the 17th century. On one hand, the sage scholar and true intellectual wrote questions and answers and contemplative texts and composed plays and music. On the other, he was an avid dice player and gambler. The Katzenellenbogen family, the father Meir, the son Judah, and the grandson Saul Wahl, were also well-known – Wahl for a legend in which he was claimed to have been King of Poland for one night.

But there is no doubt that the main contribution of all of Venice and of its ghetto were the city’s printing houses. The invention of modern printing, about 100 years prior, occurred in a canaled city that was ready and willing. One publishing house belonged to Daniel Bomberg, a Christian from Antwerp. He established a Hebrew print house on the recommendation of a friend – a Jewish convert to Christianity – who persuaded him to target the “People of the Book.”

Daniel Bomberg’s publishing house earned its name in the pantheon of creation mainly for printing editions of the Babylonian Talmud that were the first to gather all of the Talmudic tractates. Bomberg’s innovation was in its layout of the Talmud, in which Rashi’s commentary and the Tsofot appear on the outer margins of the page.

Bomberg assembled a staff of learned and exacting sages to prepare and proofread the texts for printing. To this day, every edition of the Babylonian Talmud, whether traditional of progressive, follow the model established in Venice. One of the first editions of the Babylonian Talmud published by Bomberg sold at auction five years ago for the astronomical price of $11 million. Another edition will be part of the permanent exhibition at the Beit Hatfutsot Museum of the Jewish People, scheduled to open in October this year.

The Venice Ghetto was home to the city’s Jews for 281 years. In 1797, when Napoleon conquered the city, the ghetto was dismantled in response to its new ruler’s order. Jews became equal citizens and retained their status when Venice gained its independence in 1848.

Mussolini’s fascist regime and ally of Hitler reintroduced race laws in Italy in 1938. More than 200 of some 1,200 Venetian Jews failed to return from the concentration camps.

Some 450 Jews now live in in the city. Isolated again in these troubled times, this time they join the rest of the city’s and the nation’s residents in the battle against the CoronaVirus.

Translated by Varda Shpiegel