Itamar Kremer

A mysterious disease erupted in the mid-14th century called the Black Death. The disease, caused by the Yersinia pestis bacteria, began in Mongolia and spread quickly to China. It spread to Europe following a battle between the Mongolians and the Genovese army on the Crimean Peninsula. Dead bodies were catapulted toward Italy, in what appears to have been the first use of biological warfare, if you will.

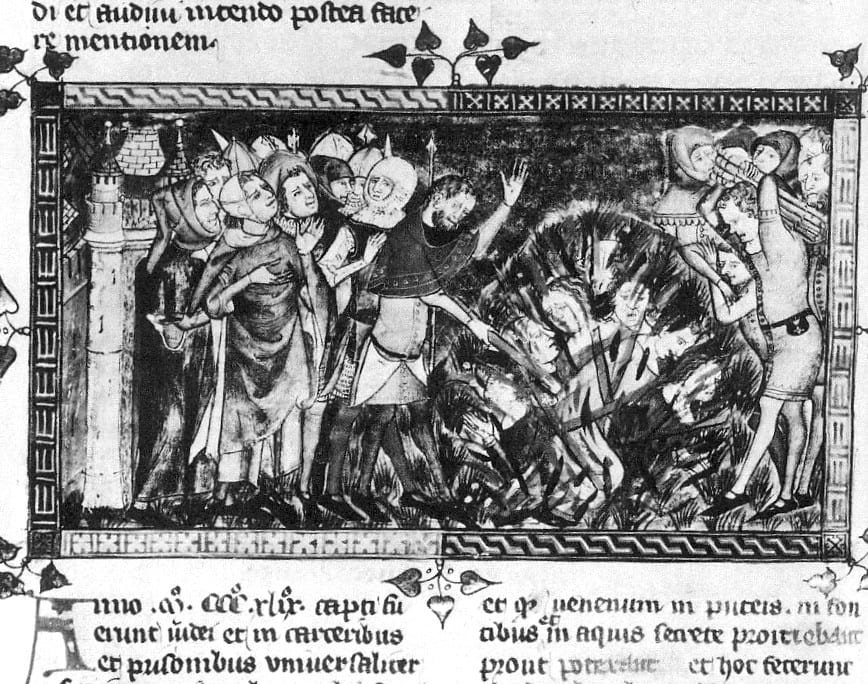

The disease spread throughout the Old World, killing 20-25 million Europeans and another 35 million Chinese within a decade. As soon as the disease arrived in Europe in 1346, some blamed the Jews for leisurely poisoning wells. When the disease’s virulently fatal nature became clear – mainly in 1348-1349 – it was accepted as fact that the Jews were to blame.

This was not a new notion. During the 500 years that preceded the plague, European demographics, urban trade centers and major ports thrived, and Jews engaged mainly in local commerce. Jewish communities were subject to no lack of persecution, including the Crusades and major exiles from England and France in the late-13th and early-14th centuries.

But the plague brought a completely different type of persecution. This was not just economic oppression, unfair taxation, or even marking Jews with a yellow or purple patch. This was real slaughter. The masses ignored Pope Clement VI’s bull that the Jews were not to blame, King Carl IV of Germany’s explicit policy and even the public statements of a significant number of European municipalities. A purely economic matter was at play here. Jewish property was perceived to belong to royalty or cities. Jews worked under licenses, trading, profiting and earning their daily bread in the only occupations permitted to them. Kingdoms and local authorities were thus empowered to announce when and where Jews could be killed, how their property would be divided and by whom.

But the masses did not obey. Extremist religious groups, local actions, a series of religiously, economically and socially based mass murders, and mainly unbridled hatred and fear of the Other ensued.

Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed. Jews in Basel were burned in a structure created solely for that purpose, walking distance from the casino in which the First Zionist Congress was held 550 years later. More than 1,000 Jews were killed on the night of Valentine’s Day, and Jews were forbidden from living in the city for 100 years. A mass suicide of Jews took place in Frankfurt and the Jewish community of Erfurt was completely wiped out. Information regarding the location of a bounty of treasure, buried by the community’s sponsors, was also erased when the plague began. That treasure was coincidentally discovered during an archaeological dig in 1998. Beit Hatfutsot’s collection includes a wedding ring that was part of that treasure.

Most of the Jews who inhabited and survived the pogroms in Germany, Austria, France, and Switzerland emigrated to Poland, where King Casimir (Kazimierz) III displayed a tolerant policy toward Jews and other minorities. A smaller number fled to Spain, where Jews were briefly offered shelter until the pogroms and Massacre of 1391 meant their days were also numbered.

Despite commonly held belief, we cannot say whether Jews died in greater or lesser numbers of the disease than they did of their neighbors. Many historians believe that halacha mandating hygiene practices like netilat yadayim (handwashing), quick burial of the dead, and tahara (ritual purity); and arvut hadadit, mutual responsibility among members of the community protected Jews – at least from death – by reducing the spread of disease. Halacha also contains strict rulings on isolation

during an epidemic like “When there is an epidemic in the town keep your feet inside your house (Bava Kamma 60b.)” or the Halacha’s command against double-dipping: “One should not bite off a piece [of bread] in front of his fellow and put it into the bowl of food from which he eats (Masechet Derech Eretz).”

But one must remember that all Halachic laws were not enforced and observed to the same extent at the time, and that the Jews faced difficult environmental conditions: The Jewish Quarters were typically relatively crowded, located far from city centers and adjacent to city walls. Jewish Quarters in cities along rivers were typically located on their banks, in relatively unsafe areas near forests and wildlife.

We know that many Jews died directly – not just indirectly – from the disease. There is little documentation about the lives of Jews in that period beyond fear, harsh decrees, and persecution. Halacha ceased completely to develop during those decades; yeshivot were dismantled, and the center of learning and religious ruling moved.

Rabbi Jacob ben Asher, Ba’al Haturim, penned the Arba’ah Turim (“Four Columns”), a few years before the plague broke out in Cologne, Germany. The collection of halachot practiced during that period was a testament to Western European Jewish life. It is actually eulogies and depictions of death that shed light on Jewish life during those dark times.

An epitaph for a boy named Asher ben Turiel has remained inscribed on his tombstone for hundreds of years in the surviving Jewish cemetery in Toledo. We can learn a great deal from his father’s farewell to his dead son about how the Jews of Toledo lived:

This stone is a memorial / That a later generation may know

That underneath it lies hidden a pleasant bud / A cherished child

Perfect in knowledge / A reader of the Bible

A student of Mishnah and Gemara / Had learned from his father

What his father learned from his teachers / The statutes of God and his laws

Though only fifteen years in age / He was like a man of eighty in knowledge

More blessed than all sons: Asher – may he rest in Paradise /

The son of Joseph ben Turiel – may God comfort him /

He died of the plague, in the month of Tammuz, in the year 1349 /

But a few days before his death / He established his home /

But yesternight the joyous voice of the bride and groom /

Was turned to the voice of wailing /

And the father is left, sad and aching /

May the God of heaven / Grant him comfort /

And send another child / To restore his soul /

Forty years later, French Jewish physician Jacob ben Salomon wrote a work entitled “Great Mourning,” in which he describes his daughter Esther’s last moments. She died of a secondary outbreak of the Great Plague in 1383, weeks after her brother and sister, Israel and Sarah, also died. Esther expressed her few final wishes on her deathbed: She asked that her money be donated to charity and her clothes to the poor. She asked that her uncle leave the room before her death, because as a Cohen (member of the priestly class), he was forbidden from being in the presence of the dead; and that her husband not come to her side because she was ritually impure according to the laws of niddah. She asked that her husband name a future daughter after her, and that her sister not take her place as his wife. Jacob ben Salomon eulogized his children by noting that during Esther’s final moments, she strictly observed the letter of Jewish law.

May we not know his suffering. Great health to all.

Translated by Varda Spiegel