Winter 1759. Some 2000 Jews – men, women, and children – gathered in the central square in front of Lvov, Poland’s cathedral. All but the wailing infants were mum. The frigid bone-penetrating cold was beginning to claim victims. The occasional sound of a body hitting the ground was heard.

Elisha Shor – of the famous Rohatyn Shors – was among the Jews in the square. He begged the cathedral’s leaders to give at least the elderly and the babies food and shelter. He told them that the Council of Four Lands, the central Rabbinic authority of Polish Jewry, had issued a bill to excommunicate them. The council has accused us of Sabbateanism, heresy, and lawlessness, he said. It is forbidden to rent us a home or hire us, and our children have been expelled from educational institutions. We are starving.

The Church elders knew very well that in those days, the fate of a Jew who did not belong to the community was a painful death. The Bishop of Lviv told Elisha, “You will be given shelter and food on three conditions. First, that you publicly declare that your Talmud spreads lies about Jesus. Second, that you confess to using the blood of Christian children to bake matzas. And third, that you convert to Christianity.” Elisha Shor turned around to face the 1,999 questioning pairs of eyes. They stared at him in nerve-wracking anticipation. He took a deep breath, stood up straight, and told the bishop, “That is what we will do.”

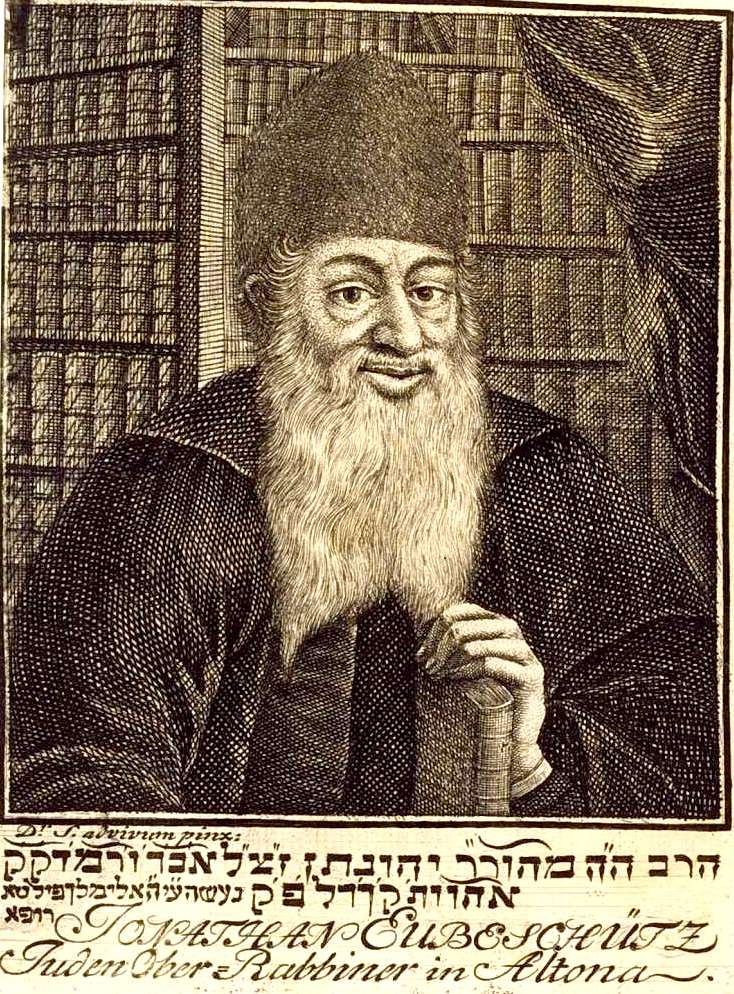

How did we arrive at this cataclysmic moment? Our story begins 65 years earlier. In 1694, a baby named Jonathan Eybeschutz was born in the city of Pinchov, Poland to Sheindel nee Tzuntz and Rabbi Natan Neta, an offspring of Rabbi Natan Neta Shapira the “Megale Amukot (revealer of the depths).” Eybeschutz, who grew up in a family of sages, was known to be a child prodigy and brilliant Talmud scholar.

When he turned bar-mitzva age, a tragedy befell his family: His father passed at a young age, leaving him an orphan. Before he died, his father asked Rabbi Meir Eisenstadt – known as the “Panim Me’irot” for his major work, “Shu”t Panim Me’irot” – to adopt his son and see to his education. The loyal rabbi fulfilled his friend’s last request. Eybeschutz moved to Rav Meir Eisenstadt’s home in Prossnitz, Moravia and continued to excel in his studies.

This was the point at which the man who fired the opening shot in this war appeared. Among the young teachers appointed by Eisenstadt to teach Eybeschutz was Rav Yehuda Leib Prossnitz, a secret Sabatean and student of Rabbi Nehemia Hayun, a well-known 18th-century leader of Sabateanism. The young teacher and his charge shut themselves in a room and – in addition to studying the fine points of Talmudic pilpul and Halachic ruling – they devoted themselves to studying the Kabbalah, reading the Holy Zohar, and examining known Sabatean literature like the “Raza DeMehimnuta,” attributed to Sabbatai Zevi. Sabbateanism enchanted the talented boy. He devoted his days to the Torat Hanigla rulings of poskim (mainstream religious commentators), and his nights to the Torat Hanistar commentary of Kabalistic sources.

A brief aside. While this sounds anachronistic to us, a bitter struggle took place throughout the 18th Century between the Sabbatean movement and the rabbinic establishment. A near half-century after Sabbatai Zevi’s death, his ideas spread like wildfire throughout Europe. For example, it was said in 1726 about the city of Nadvorna, Galicia that “everyone in the entire city is Sabbatean,” and that “all the gifted scholars there [in Rohatyn, Ukraine] were Sabbatean” or in Yiddish, “Shabbtai Zvinikes.” The rabbinic establishment feared the anarchistic principles embodied in Sabbatean doctrine and the explosive Messianic material it contained. The elite required obedience and the Sabbateans were a thorn in their sides that must be expunged.

Let’s return to Jonathan Eybeschutz. The boy did not limit himself to Sabbatean concepts – he had plenty of Shas Mishna study and poskim rulings under his belt. And in 1710, he was privy to a worthy match with a Torah genius of his ilk. Her name was Elkele and she was the daughter of Rabbi Isaac Spira, the Chief Rabbi of Prague, after he was married, Eybeschutz served as a rabbi in the Great Beit Midrash in Prague, considered the greatest Beit Midrash in Europe.

In 1725, the troubles began. A complaint about Eybeschutz’s affinity for Sabbateanism was filed with the Prague Rabbinate. Eybeschutz was subsequently obligated to subject himself to a humiliating ritual during Kol Nidrei Yom Kippur services in the Great Synagogue of Prague. He was forced to face the entire Jewish community of Prague and admit that he was a Sabbatean. And that was only the beginning. A number of years later, Eybeschutz was offered the position of chief rabbi of Metz. There too, a surprise awaited him. It turned out that Elkele’s aunt lived in Metz and was coincidentally the widow of Rabbi Yaakov Reicher, the city’s chief rabbi who died not long before Eybeschutz’s arrival. When Eybeschutz’s name was mentioned to replace her husband, “Aunt Gittel” announced that she was present at an event that took place during Kol Nidrei services in Prague and that she refused to let Eybeschutz – who was tainted with Sabbateanism – replace her husband. She failed to heed sage advice to “keep this all in the family.”

But the Metz affair was only a promo for the major storm that would erupt in 1750, when the leaders of the Jewish community in Altona, Hamburg, and Wandsbek – an area known as the Three Communities – offered Eybeschutz the prestigious position of chief rabbi of that district. For Eybeschutz, this was a dream come true. For another man, it was a living nightmare.

Yaakov Emden, who is known as the Ya’avetz, was the son of the Hacham Tzvi Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch and the grandson of Rabbi Zalman Mirlesh. Both of them had served as chief rabbis of the Three Communities. When Ya’avetz heard that Eybeschutz was to be seated on what was once his father’s and grandfather’s rabbinic throne, his response was “over my dead body.” Ya’avetz, a Torah genius in his own right, declared a war to the death against Eybeschutz and the Sabbateans.

Ya’avetz established a printing house for no other purpose than to print 20 books to thwart Eybeschutz’s appointment. You heard right: Only to condemn Eybeschutz and the Sabbateans. But that didn’t satisfy him. Eybeschutz’s step-brother was none other than Rabbi Meir of Biala, Ya’avetz’s brother-in-law who was also coincidentally a representative of the Council of Four Lands – the rabbinic authority over all of Polish Jewry. Ya’avetz dispatched his brother-in-law to oppose Eybeschutz, his step-brother. And from that moment forward, the council waged a McCarthyesque witch hunt against Eybeschutz and the Sabbateans. This culminated in events including the “Lvov Excommunication” in which 2,000 Jews were forced to convert in that city’s cathedral.

The five years in which Rab Eybeschutz served as the chief rabbi of the Three Communities were overshadowed by the battle against him. Ya’avetz relentlessly attacked him until Eybeschutz finally surrendered. He died exhausted and emotionally scarred in 1764.

*The story appears in Professor Rachel Elior’s book “Israel Baal Shem Tov and his Contemporaries*

(Translated by Varda Spiegel)