“My girlfriend and I are Russian revolutionists and freethinkers, but our parents want us to have a religious wedding—what should we do?”

“Should I marry a woman with a dimple in her chin, when everyone says that people with dimples in their chins will lose their first husband or wife?”

“I was a prosperous businessman in Warsaw, but I have not managed to succeed in America; should I go back to Warsaw?”

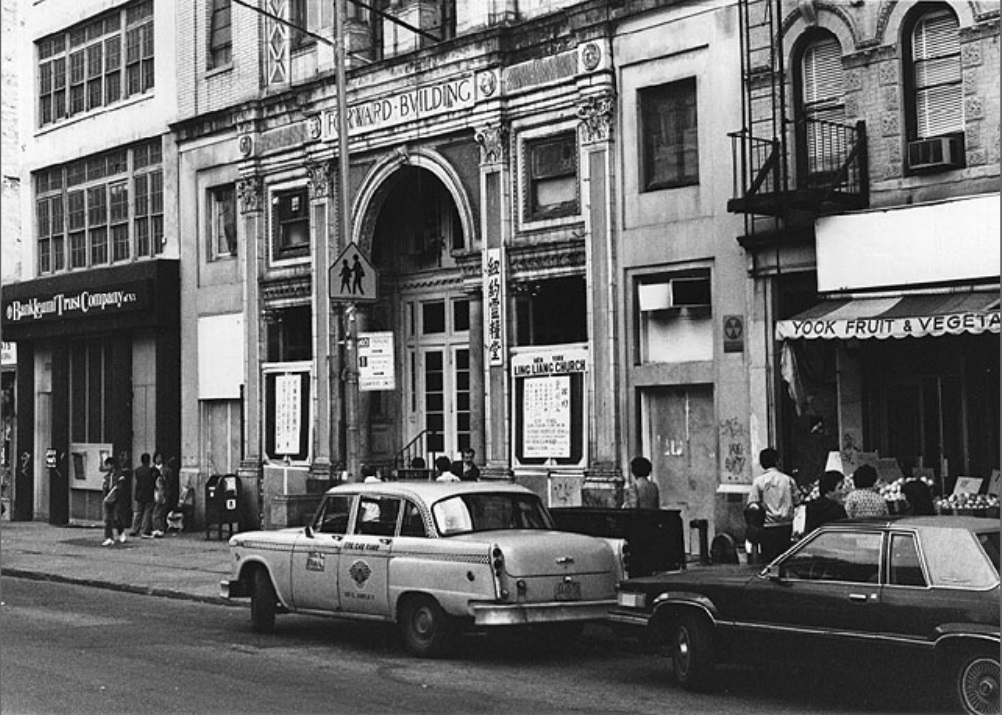

These are just some of the hundreds of questions printed by the Yiddish newspaper Forverts (פֿאָרווערטס) in its advice column, A Bintel Brief (אַ בינטל בריוו, A Bundle of Letters). The Forverts was established in New York City in 1897 by Yiddish-speaking socialists, and quickly became the most popular and widely-read newspaper—in any language—in Manhattan, eventually reaching a circulation peak of more than 275,000 before America closed its doors to Jewish immigrants. Abraham Cahan, the paper’s legendary editor, began the column in 1906, and it soon became one of the most popular sections of the newspaper, with friends and families gathering to debate the letters and the editor’s responses; for instance, one letter, from a young man asking whether he should marry a woman he did not love, prompted a response from a group of 68 people who had met in the park to discuss the question.

A Bintel Brief was more than entertainment; it served as a lifeline for Eastern European Jews who were trying to acclimate to their new lives in America. No topic was taboo: from love and sex, to politics, to religion the letters to A Bintel Brief tell both the unique and individual stories of each letter writer, as well as universal and timeless stories about immigration and acculturation; generation gaps and family conflicts; economic worries; and the ever-present, simultaneous pulls of the Old World and the New. A Bintel Brief was a place for Yiddish-speaking immigrants, who had so little power in their everyday lives, to express themselves and take control of their own stories. For example, one short letter from 1906 simply describes how a 13-year-old boy who worked with the writer in a Lower East Side sweatshop was docked pay (from an already meager salary) for arriving 10 minutes late. As a working immigrant struggling to make ends meet, the letter writer could not say anything to his bosses. What he could do, however, was write to A Bintel Brief and register his anger somewhere, at least.

Some letters provide intimate and personal stories from people who had experienced traumatic historical events. One woman who survived the Kishinev pogrom at the beginning of the 20th century wrote to ask whether she should tell her fiancé that she had been sexually assaulted during the pogrom. Another man, thinking that his wife and children had been killed during the pogroms married another woman and had a child with her, only to discover that his first wife was, in fact, alive in Russia, and wrote to A Bintel Brief asking what to do. Letters were sent from survivors and family members of victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, the 1911 fire that left 147, mostly immigrant women, dead. Survivors wrote about their terror and seeing their friends burn to death, while family members of victims described their sorrow, and their struggles to make ends meet after having suddenly and violently lost a much-needed source of income.

A Bintel Brief became another platform for the paper to advocate for its ideology, railing against the inequality that forced so many people to subject themselves to all kinds of abuse and work themselves to the bone in order to live. The column advocated for women’s enfranchisement, equal rights for African Americans, and for religious Jews and “freethinkers” to live according to their beliefs, while respecting each other. More than an advice column, it was a place Jews could unburden themselves, and believe in the better, more equal future that they hoped to find in America.

Rabbi Rachel Druck is the Manager of International Foundations and Projects at the Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.