During the Holocaust a number of incredibly brave individuals risked their lives to save those of their friends, neighbors, or even the lives of strangers. One of the most remarkable stories of courage and creative thinking in the face of danger is that of Dr. Eugene Lazowski, who managed to create an entire typhus “epidemic” in order to keep the Nazis at bay.

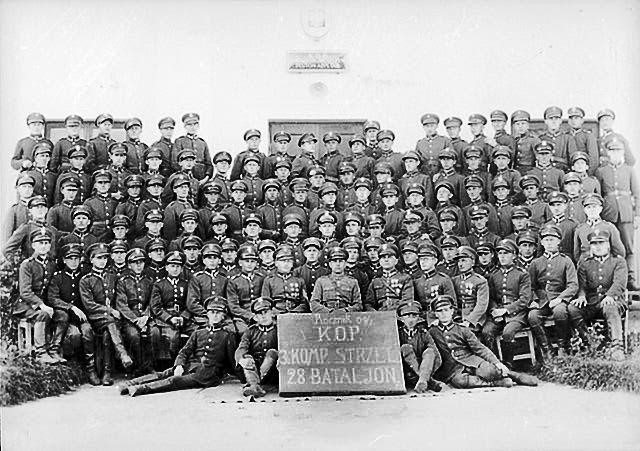

Dr. Lazowski (whose original name was Eugeniusz Sławomir Łazowski) was born in Częstochowa, Poland in 1913. In 1939, when the Germans invaded Poland, Dr. Lazowski was a young physician who had recently finished medical school and who was serving as a doctor in the Polish Army. After the outbreak of the war, Dr. Lazowski was sent to practice in the town of Rozwadów, a town in southeastern Poland with a large Jewish population.

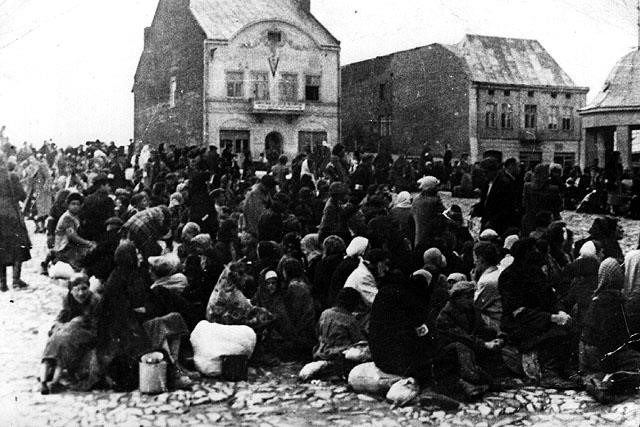

When Dr. Lazowski arrived in Rozwadów the town was under German occupation, and by the 1940s a ghetto had been established. Although he was forbidden from providing any form of aid to the Jews, as both a Catholic and a medical professional Dr. Lazowski was determined to help them as much as possible, regardless of the danger to himself. Though he could not openly treat the town’s Jews, a system developed whereby if a Jew required medical assistance someone would hang a rag on Dr. Lazowski’s gate (which bordered the ghetto). Dr. Lazowski would then know to visit the ghetto at night, under cover of darkness, and provide medical aid.

Crucially, as it turned out, it was not only the town’s Jews who sought Dr. Lazowski’s help. At one point a Polish man came to see Dr. Lazowski and his partner, Dr. Sanislaw Matlewitz. The man had been conscripted by the Germans to work as a forced laborer, and was due to return to the labor camp after two weeks of leave to see his family. The man was frantic; he desperately did not want to return, but he knew that if he failed to report back he and his family would be arrested and sent to concentration camps.

Coincidentally, Dr. Matlewicz had already been researching typhus and possible treatments and vaccines. Over the course of his work, he discovered that injecting a person with a dead strain of typhus (Proteus OX19) would be enough for them to test positive for the disease without actually causing them any harm. This was a useful discovery; the Nazis were particularly fearful of typhus and its potential to spread and become epidemic, and imposed a number of rules in order to track and prevent its spread; doctors were required to report suspected typhus cases and send blood samples to German labs for testing and confirmation, and various procedures were put into place to deal with confirmed cases.

The doctors saw an opportunity to help not only the Polish worker, but Rozwadów’s Jewish residents as well. While Jews with confirmed cases of typhus would have been killed immediately, non-Jews were quarantined. Since the Polish worker was so desperate, and was due to report back for work imminently, he became the doctors’ first test case. And indeed, after injecting their Polish patient with the dead typhus strain, the results of his typhus test came back positive and he did not have to return to work. While Dr. Matlewicz feared arousing Nazi suspicions and ultimately left, Dr. Lazowski began injecting non-Jews who came to him with typhus-like symptoms (such as the cold or stomach flu) with this dead strain, reassuring them that it was a precautionary measure. He would then take blood samples and send them to Nazi-run labs, even taking care for the injections to follow the patterns that an actual typhus epidemic would follow. Within two months, the Nazis concluded that a typhus epidemic had broken out in Rozwadów and quarantined the area. No one was allowed in—and, more significantly, no one was allowed out. This meant that the Jews within the quarantine zone were not deported from the town to concentration and death camps.

The Nazis, however, eventually grew suspicious—particularly since no one seemed to be dying in this “epidemic.” A group of German doctors and soldiers was sent to Rozwadów to investigate. Once they arrived, they were greeted by Dr. Lazowski, who had made sure to provide them with a large meal, complete with copious amounts of alcohol. As the senior Nazi official became increasingly intoxicated, he sent his underlings to examine the patients. Dr. Lazowski, meanwhile had arranged for the sickest-looking patients to be present in the clinic for the visit. Fearing infection, and lacking experience, the younger doctors satisfied themselves by merely taking blood samples, which served to confirm the “typhus epidemic,” without providing any further analysis that would have exposed Dr. Lazowski and his plan. The Jews of Rozwadów—and Dr. Lazowski’s family—remained safe.

Dr. Lazowski subsequently expanded his work to the 12 villages surrounding Rozwadów, increasing the number of people under his care, and Jews under his protection. Eventually, however, the Germans once again grew suspicious of Dr. Lazowski and the “epidemic,” and were less inclined to satisfy themselves with a short visit to check in on him. A German soldier tipped off Dr. Lazowski that the Gestapo were planning on arresting him. Dr. Lazowski and his family fled the area, bringing his work to an end. However, it is estimated that between 1939 and 1942 Dr. Lazowski saved approximately 8,000 Jewish people in Rozwadów and the surrounding area.

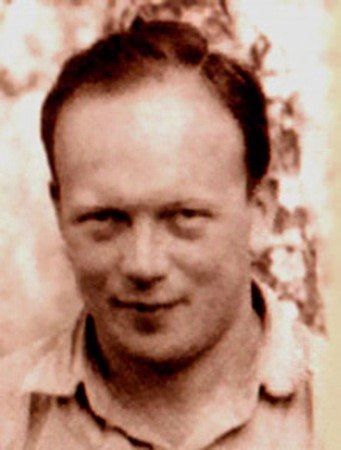

In 1958, Dr. Lazowski and his family immigrated to Chicago, Illinois where Dr. Lazowski resumed practicing medicine. In 1976 he became a professor pediatrics at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where he worked until he retired in 1988. It took years until Dr. Lazowski’s remarkable work became known; Dr. Lazowski was reluctant to speak about his wartime experiences, both because of his natural modesty, and because he was worried he would be in trouble for his actions during the war. But in 1980 he published an article in which he discussed his wartime activities; later, in 1993 Dr. Lazowski published Prywatna Wojna (My Private War), which was widely read in Poland. As a result of the publicity surrounding the book, Dr. Lazowski returned to Rozwadów in 2000 as part of a documentary about his wartime heroism. There he was greeted warmly, and with a 3-day celebration held in his honor.

Dr. Lazowski passed away on December 16, 2016, at age 92, in Eugene, Oregon. As Ryan Bank, the filmmaker who directed a documentary about Dr. Lazowski put it: “Dr. Lazowski is truly a hero in the utmost sense of the word. He risked his life to save others simply because it was the right thing to do. His story must live in so that future generations can learn from what he did”.

Rachel Druck is the editor of the Communities Database at Beit Hatfutsot.

Bibliography:

http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2006-12-22/news/0612220202_1_germans-jews-typhus

http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/how-a-fake-typhus-epidemic-saved-a-polish-city-from-the-nazis

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/dr-eugene-lazowski

https://web.archive.org/web/20110720044324/http://perspect.siuc.edu/01_fall/documentary.html