Christmas is, ostensibly, one of the least Jewish days in the calendar. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine a less Jewish day than one that celebrates the birth of a religious figure who was firmly and decisively rejected by Jews, and is traditionally celebrated with a special church mass and/or a Christmas ham. Historically, Christmas could also be a dangerous time for Jews, such as when a pogrom broke out in Warsaw in 1881 on Christmas Day.

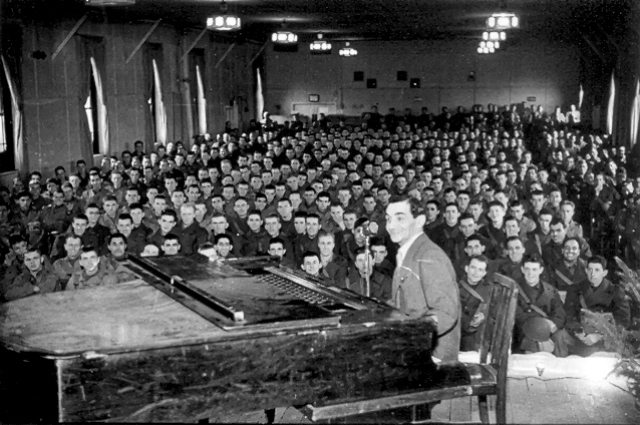

(Photo: Herbert Sonnenfeld, The Ostler Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot)

And yet, Jews have had a major impact on Christmas and the way it is celebrated in one fundamental way: through its soundtrack.

A surprisingly high number of the most classic Christmas songs—the ones that radio stations begin playing at the end of October, and which have become an inescapable and inseparable part of the emotional experience of Christmas—were, in fact, written by Jews. Fancy roasting some chestnuts on an open fire to celebrate the holiday season? Bob Wells (born Robert Levinson) and Mel Tormé can relate. Feeling cozy in your home and, not caring about the weather outside, feel the need to declare, “Let it Snow, Let it Snow, Let it Snow?” Sammy Cahn (born Samuel Cohen) and Jule Styne (born Julius Kerwin Stein) understand. You’ve left your home and are now enjoying “Walking in a Winter Wonderland?” Felix Bernard wrote just the song for you. Bing Crosby’s classic rendition of “Silver Bells,” describing the quiet joy permeating the city at Christmastime, is brought to you by the songwriting duo Jay Livingston (born Jacob Harold Levinson) and Ray Evans. If you’d like something a little more romantic, Joan Ellen Javits (the niece of New York Senator Jacob K. Javits) and Philip Springer can get you in the mood with their “Santa Baby,” famously performed by Eartha Kitt.

This pattern holds true even for the most quintessential Christmas song, “White Christmas.” “White Christmas” is not only the most recorded Christmas song, the classic version sung by Bing Crosby is the world’s bestselling single. This song, which begins with the lyrics “I’m dreaming of a white Christmas/Just like the ones I used to know” and conjures up nostalgic childhood images of glistening treetops and sleigh bells in the snow, was written by Irving Berlin, previously known as Israel Beilin, a man born in a shtetl in the Russian Empire.

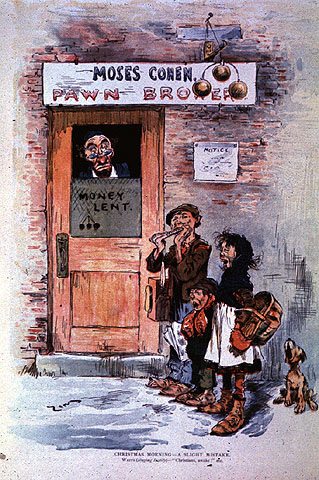

An anti-Semitic cartoon in the magazine “Judge” featuring Christmas carolers surprising the pawnbroker Moses Cohen.

(From the John and Selma Appel Collection, Michigan State University Museum, The Ostler Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot)

“White Christmas” is perhaps the most obvious example of the incongruity between the experience conjured up by the song, and the actual lived experience of the song’s writer, but to one extent or another this phenomenon of Jewish songwriters and Christmas songs points to the complicated relationship that Jews often have with the holiday. For Jews living in majority-Christian countries, Christmas is a major cultural event, even more than a religious one. It often serves as a strong recurring reminder that, in spite of how far they have come, Jews will always be outsiders.

Some of these Christmas songs can, in fact, be understood as expressing an attraction to, and alienation from, Christmas. Walter Kent’s (born Walter Maurice Kaufman) “I’ll be Home for Christmas,” while ostensibly the longing for home of an American serviceman during the holidays, can also be read as a song about the Jewish experience during the Christmas season. “I’ll be Home for Christmas” expresses a plaintive yearning for home, and references the classic components of Christmas: snow, mistletoe, a Christmas tree, and presents. But it quickly becomes clear that the singer, rather than expressing his anticipation of Christmas at home, will not actually be experiencing any of the things he is singing about; instead, he will be home for Christmas “only in my dreams.” Similarly, a Jewish person may experience the Christmas season unfolding, with the trees, colorful decorations, and the general atmosphere of celebration. But while they can enjoy the aesthetics of the holiday from afar, ultimately Christmas, and all it represents, can be home for a Jewish person “only in my dreams.”

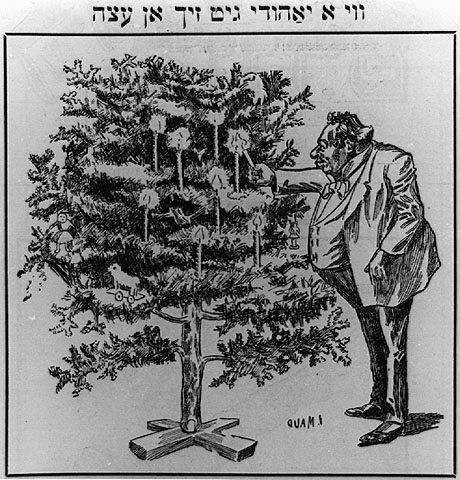

(Courtesy of Eliyahu Binyamini. The Ostler Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot)

And then there is the holiday classic “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” which can be understood as the most Jewish of all Christmas songs. The song, which was written by Johnny Marks (who also wrote such Christmas classics as “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree” and “A Holly Jolly Christmas”) was based on a tale written by his brother-in-law, Robert L. May. It is the story of a reindeer who is noticeably different from the rest of the reindeer (distinguished by his nose, no less!) and who is ostracized and made fun of because of that difference. Until, that is, the ruling authority, Santa Claus, recognizes the usefulness of Rudolph’s glowing red nose in navigating the sleigh through a particularly foggy night. Rudolph guides the sleigh, thereby saving the day for Santa, the reindeer, and children the world over. As a result, Rudolph goes from being a pariah figure, belittled and disrespected, to being beloved by the other reindeer.

It is easy to read into Rudolph the story of the Jewish people, particularly in America. It is the perfect fairy tale for a people who experienced similar ostracism and discrimination because of how they were different, but who nonetheless longed for acceptance, both from indifferent or cruel governments, and their fellow citizens. And what better holiday to prove one’s worth as an American, and making the case for acceptance, than by saving Christmas?

Although Christmas may not be a Jewish holiday, the music that gives Christmas its tone and atmosphere was often written by Jewish people and may even, at times, be said to have a particular Jewish character. This drive on the part of those who experienced Christmas as outsiders to nonetheless contribute to, and be part of, Christmas, reveals a certain longing to no longer be outsiders among their peers, their country, and the Christmas holiday.

Rachel Druck is the editor of the Communities Database at Beit Hatfutsot-The Museum of the Jewish People.